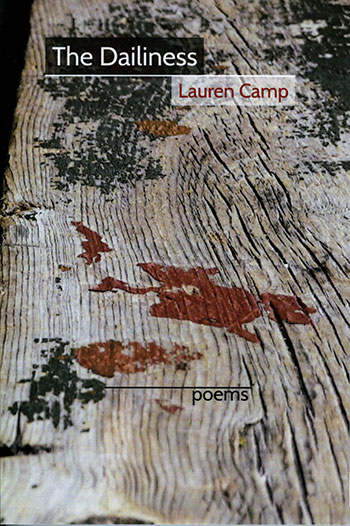

Lauren Camp

Lauren Camp

Edwin E. Smith Publishing ($14.95)

by Richard Oyama

“The test of a first-rate intelligence is the ability to hold two opposed ideas in mind at the same time,” F. Scott Fitzgerald wrote, “and still retain the ability to function.” That was close to how I experienced The Dailiness, Lauren Camp’s stirring new poetry collection. The book has scope, complexity, and amplitude—a work of fine poetic intelligence. The title poem is a sort of daybook of images, testifying to Camp’s loving attention to detail, while the first poem, “Looking Around These Days,” catalogues varieties of unease and our compensatory behaviors to quell disquiet. It is a snapshot of our dark cultural moment.

The poet renders the bond between herself and her late mother with precision and unflinching frankness: “Our relationship / was always that haunted, that taut and that still” (“How I’d Explain What Kind of Mother She Was”). The poem is a remarkable exploration of the complexities of familial tenderness, rancor, and “hidden ways” of love. The mother braids “scattered people" into "a galaxy of necessary stars" ("For Those of You"). In the same poem, “Our faces / were her fiction, her tongue flowering with what was written / on her eyes” as though she has the power to transform those around her. The breathless, unpunctuated "Ten Years" begins, "where did you day and day gone / and you in the cement the blossoms the wind." It implies our helplessness in face of death, the contingency of life.

“A Colloquy on Water” is rooted in the thirsty New Mexican landscape: “Look here, where the wild olive lives, the berried sumac, / this earth, its tart face waiting, the crabapple weeping, / the honey locust, black currant, purple ash, the amurs / and cottonwoods standing, stiffening.” In "Journey," language assumes the garments of culture: "words that tickle and stumble, words in brown jackets, / brown shoes, words that hurl and kick, pray and dance." Auden said of Yeats, "Ireland hurt you into poetry." For Camp, that tormented country summons the lyrical impulse.

The jazz poems are especially stunning, a visual/verbal correlative to the music. From “What You Might Hear:” “His horn, that pliable prophet of conduct, offers its / sequence of agony, exodus, / the fanatical fancy of finding devotion.” It’s as though Ornette Coleman’s free jazz becomes a form of spiritual and moral practice. The personal anguish of his search for a sound mimics the abduction, “exodus” and enslavement of African people—or, for that matter, all diasporic peoples.

The final poem, “When,” is a series of propositions in the form of couplets: “When you shiver, you enter the radical center / —or tangible timidity.” Once more, there is the sense of the conditional, but also that the essence of what it means to be human is the capacity to be vulnerable, to “shiver.”