by Rasoul Sorkhabi

As Anglophile readers and art lovers already know, the Bloomsbury Group included several British writers, artists, and intellectuals who lived, studied, or worked together in or near London’s historical Bloomsbury district in the first half of the twentieth century. Many of these figures are little known today, but some, like Virginia Woolf and E.M. Forster, are still household names. Two recent books, both profusely illustrated and written by authorities in the field, rejuvenate the memory and legacy of the Bloomsbury men and women who, even though they did not consider themselves an official organization, ushered in new waves of artistic expression.

The Bloomsbury Group began in 1904 when Vanessa Stephen (aged 25) and her siblings Thoby (24), Virginia (23), and Adrian (21) moved from their parental home to a new one in Bloomsbury. Their father, the prominent literary critic Sir Leslie Stephen, had died in February that year, and their mother Julia had passed in 1895, after which the family lived in grief. The four siblings, all intellectuals, wished to leave their conservative, patriarchal, gloomy Victorian background behind and create a “house of their own.” As Virginia recalled after she married Leonard Woolf in her account titled “Old Bloomsbury,” “We were full of experiments and reforms. We were going to do without table napkins . . . we were going to paint; to write; to have coffee after dinner instead of tea at nine o’clock. Everything was going to be new . . .”

Thoby Stephen, a Cambridge graduate, invited his circle of friends to join the Stephens’ Thursday evening “at home” gatherings; known as the Cambridge Apostles, this group included Lytton Strachey, Leonard Woolf, Clive Bell, John Maynard Keynes, and E.M. Forster. The Cambridge contingent was greatly influenced by the English philosopher George Edward Moore, author of Principia Ethica (1903), who believed in the importance of physical beauty, pleasure, and personal relationships in life, rather than the abstract, metaphysical, or idealistic views of the nineteenth century—an idea which the Stephens siblings adopted wholeheartedly as well.

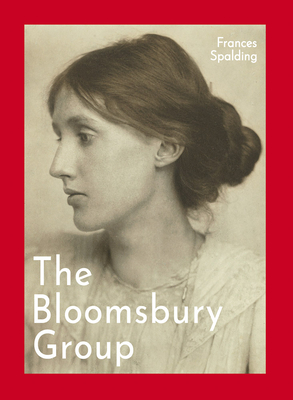

Frances Spalding’s The Bloomsbury Group (National Portrait Gallery, $24.95) is published by the National Portrait Gallery in London, which houses many photographs and paintings of Bloomsbury Group members. Spalding (who has previously written biographies of Vanessa Bell, Roger Fry, and Duncan Grant) touches on the life stories of nineteen Bloomsbury writers, painters, and intellectuals. Vanessa and Virginia Stephen, who did the most to hold the group together, are justifiably pivotal figures in the book; missing from the list, however, are their brothers Thoby and Adrian. Although Thoby died in 1906 (an untimely death from typhoid fever he contracted during a trip to Greece), his death brought the Cambridge Apostles and the Stephens closer. Adrian introduced not only his gay friends Duncan Grant and David Garnett but also Freudian psychology to the group, becoming (along with his wife Karin) one of the first British psychoanalysts. Vanessa, shortly after the death of Thoby, married Clive Bell, and the couple had an open marriage; indeed, open marriages, triangle relationships, homosexuality, and bisexuality were common among the many members of Bloomsbury.

Reading through Spalding’s book, it becomes apparent how close-knit the Bloomsbury Group was. For instance, Freud’s Complete Psychological Works—published by the Woolf’s Hogarth Press, which also released books by T. S. Eliot, Vita Sackville-West, and Virginia Woolf herself—was translated and edited by James Strachey (Lytton’s younger brother). The index for the entire twenty-four volumes was compiled by Frances Partridge, the wife of Rex (“Ralph”) Partridge, who was previously married to Dora Carrington (Lytton Strachey’s partner).

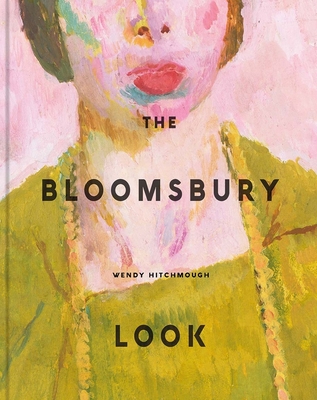

Wendy Hitchmough’s The Bloomsbury Look (Yale University Press, $45) uses nearly 180 archived photographs, paintings, and cultural materials to visualize the lives and works of the Bloomsbury Group. Hitchmough is well positioned to write this fascinating book: She was curator for more than a decade at Charleston Farmhouse in Sussex, where the Bloomsbury painters lived and created art works beginning in 1916 (Duncan Grant continued to live there until his death in 1978). The Bloomsbury Look begins with an informative introduction to the group’s imagery and identity, followed by chapters analyzing the group’s photographs, fashions, and their decorative arts and paintings—all a big part of the group’s activities.

Perhaps at no point in history had literary and visual artists so closely interacted with each other as happened in Bloomsbury. Virginia Woolf, in search of a modern literary style, was so impressed by the post-impressionist works of her painter friends that she set aside the rigid rules of plot and characters, and created novels based on “stream of consciousness” and “inner dialogue,” as evident in Mrs. Dalloway, To the Lighthouse, and Orlando. Paintings of humans with no facial features found their equivalence in Woolf’s novels as non-articulated feelings and meanings. The Bloomsbury artists were not interested in big-picture politics or historical heroes; they were more concerned with ordinary people and small things of daily life. Not surprisingly, the members inspired and supported each other in many ways; they read and critiqued each other’s works; they painted each other’s portraits; they wrote thousands of letters to each other and wrote about each other in diaries as well as books (Virginia Woolf’s biography of Roger Fry was published in 1940, and E.M. Forster’s biography of Virginia Woolf was published in 1942, only a year after Woolf drowned herself).

The sheer quantity of writings, paintings, and cultural materials that the Bloomsbury Group produced is staggering. The group was active, on and off, for six decades, from 1904 until the death of Vanessa and Clive Bell and Leonard Woolf in the 1960s. Interestingly, as the Bloomsbury leaders were fading away, their legacy was starting to be rediscovered by a new generation of free spirits, hippies, and feminists. The Bloomsbury Group came mostly from upper-class families; they, however, rejected bourgeoise mentality, and created their own sort of fashionable Bohemian lifestyle. Centennial celebrations of the Bloomsbury Group in 2004 coincided with the death of Francis Partridge, aged 103, the last surviving member of the group.

As the bibliography at the end of Hitchmough’s book shows, a large number of books have been published on the Bloomsbury Group: There are individual biographies as well as coffee-table books, encyclopedic handbooks, and detailed histories of the entire group (one of the earliest ones was written by Quentin Bell, Vanessa Bell’s son). Nevertheless, these two new illustrated works by Spalding and Hitchmough bring a fresh breeze to the life stories and legacy of the Bloomsbury Group, which has exerted a huge impact on literature, art, thought, and even fashion in our age.

Click here to purchase this book at your local independent bookstore

Rain Taxi Online Edition Summer 2022 | © Rain Taxi, Inc. 2022