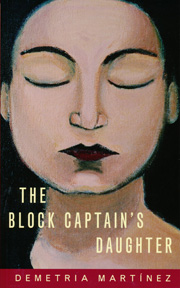

Demetria Martínez

Demetria Martínez

University of Oklahoma Press ($14.95)

by Jenn Mar

In her highly anticipated The Block Captain’s Daughter, Demetria Martínez lays the groundwork for a new understanding of Chicano and Mexican-immigrant identity in a novella that follows six activists and immigrants as they experience the vicissitudes of recognition and daily life.

Months after crossing the Mexican border on foot, the protagonist, Lupe Anaya, waits tables at a local taqueria in the “humble promised land of Albuquerque, New Mexico” while waiting for the birth of her child, Destiny. Her baby’s Salvadorian father, Marcos, has left the country, so at night Lupe reads Harry Potter books aloud to nurse fantasies of an Ivy League-bound baby and writes letters to Destiny. These letters are built on fears of her child becoming a “ketchup Mexican,” on resentments toward the North American Free Trade Agreement that destroyed countless Mexican families, and on hopes for a better life, never failed and never delivered until Destiny’s arrival.

Supporting Lupe are two activist couples: Peter and Cory, and Maritza and Flor, whose private recognitions about their cultural identities are plaited together. In the company of his partner, Cory, a mestiza with deep cultural roots, Peter sees himself as “just another white guy” suffering from cultural amnesia, who co-opts cultures by mastering foreign languages and perpetually reinvents himself. We come to see their relationship differently when Cory reveals that she can barely roll her R’s and feels like “Peter’s English subtitle.” The second couple struggles to define a private life within their activist obligations: Maritza finds their three television sets intolerable, but Flor, in the wake of 9/11, is transfixed by news images, fearing that “something else might happen.”

Written across many voices and points-of-view, the book is interspersed with Lupe’s letters. This innovation gives readers a series of variant interpretations of characters, thereby fixing and complicating identity.

The Block Captain’s Daughter welcomes possibilities more than dangers. At times Martínez’s characters come off as too agreeable and unfailingly dignified, even in circumstances where their political histories are at odds. Most of the drama happens offstage, and characters, inconceivably perceptive about their political representations and inner lives, have a propensity to spout expository history and leftist wisdom on “anti-immigration racists,” “capitalism . . . in its death throes,” and factory relocations that left “hundreds of [Mexican] women with no way to earn a living.” Still, these features point to the book’s intellect, its admirable concern for immigration reform, and positive representations of diverse communities.