Fado, Salazar, Pessoa, and Saramago

A Report from Lisbon’s DIS/QUIET Literary Program

by Mike Schneider

Lisbon, aka Lisboa, lies at the expansive mouth of the Tagus River—one of the best big-ship harbors in the world. It has been home to a sea-faring culture since before the Middle Ages and to ship captains like Vasco da Gama, who in 1498 was the first European to complete the perilous voyage around the Cape of Good Hope. His journey to India opened trade for cinnamon, ginger, and other spices such as prized tellicherry, the King of Peppers, from the Malabar Coast.

From this commercial bonanza, as we learn in school, Portugal became a world power. Its empire grew to include Brazil, from which Afro-Brazilian traditions of music developed that in the 19th century seeped back across the Atlantic to Lisbon. This musical gumbo, a byproduct of the slave trade, became known as fado. At least a couple hundred years old and often thought of as Lisbon’s traditional music, fado — the Portuguese word for “fate” — can be compared, imperfectly, to the blues. Sung by fadistas accompanied by Portuguese guitars (think 12-string mandolin) fado expresses unattained desire, deep longing, and passionate sorrow.

Not well known—according to ethnomusicologist Rui Vieira Nery, who spoke at the 2019 DIS/QUIET Literary Program—is that fado’s deep yearning for something better, something more than reality is also, inseparably, an expression of radical politics. By the late 19th century, this included Marx, anarchism, and the union movement. By that time, says Nery, Portugal’s leading historian of fado, “fado was essentially a working-class song—very politically committed. You had fados talking about Kropotkin, Bakunin, Marx—and even Lenin later on.”

Now a recognized style of world music as well as a Lisbon tourist attraction, fado arose from a subculture of poverty and violence, adds Nery, in sailors’ bars and brothels, in the back streets of Lisbon’s harbor night-life. Students and intellectuals mixed with working-class Lisbonians, men and women, leading to, for instance, a fado from 1900 that begins: "May 1st!/Forward! Forward!/O soldiers of freedom!/Forward and destroy/National borders and property."

It comes as not much of a surprise, then, that fado went into hiding, became an underground culture, when Antonio Salazar came to power. Taking control in the late 1920s—through a military coup that overthrew a shaky republic—his regime lasted until Portugal’s “Carnation Revolution” of the mid-1970s. Less well known than Hitler, Mussolini, and Franco, and more subtle in wielding tools of oppression, Salazar was the 20th century’s most enduring dictator.

A well educated, staunchly Catholic, fiercely anti-communist professor of economics and life-long bachelor, Salazar gets historical credit for sagaciously managing Portugal’s economy, which had been on the brink of ruin before a 1926 coup. Harry Potter fans can unknowingly be reminded of Portugal when they think about “Salazar Slytherin.” Not only the reptilian sound of the words led J. K. Rowling to this name for her ultimate antagonist; Rowling taught English as a foreign language in Portugal in the early ’90s and drew on Portugal’s fascist past in creating her fictional world.

As in Spain, where people are still learning, literally, where the bodies of Franco-ist state terrorism are buried, Portugual is still documenting repression during nearly fifty years of Salazar’s regime. How did it happen that most democratic institutions dissolved? The story unfolds in an effectively curated exhibit of photographs, audio, video and original documents at Lisbon’s Aljube Museum of Resistance and Freedom. A Moorish word meaning “waterless well,” the Aljube is a gray, four-story building behind the main cathedral in central Lisbon—almost unnoticeable except for its imposing iron-barred door. Once a Muslim prison, a jail during the Inquisition, the Aljube re-opened as a political prison in 1928. In cells barely big enough for one person, the PIDE (International and State Defense Police) held Lisbonians for interrogation.

Of the more than 3,000 people brought in over several decades, usually for short stretches of a few days that served as firm warning, some were never seen again. Usually identified by informants as “enemies of the state,” often on the basis of overheard conversation, these detainees underwent electric shocks, sleep deprivation, beatings and isolation.

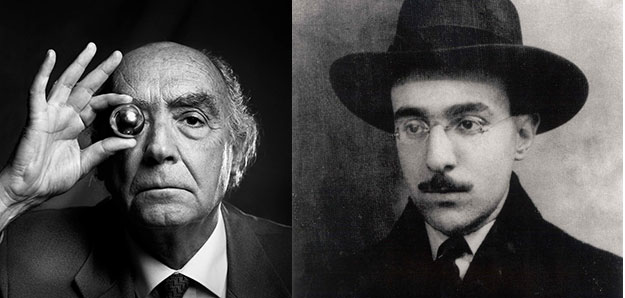

Pessoa’s Disquiet

Until the last months of his life, none of this registered in the literary work of Fernando Pessoa. Still relatively obscure outside the Portuguese-speaking world, Pessoa has gained wide regard since the 1980s as one of the great writers of the 20th century. Until he died in November 1935, likely from a used-up liver, he lived in Lisbon amid the nascent Salazar regime’s increasing authoritarianism.

Until the last months of his life, none of this registered in the literary work of Fernando Pessoa. Still relatively obscure outside the Portuguese-speaking world, Pessoa has gained wide regard since the 1980s as one of the great writers of the 20th century. Until he died in November 1935, likely from a used-up liver, he lived in Lisbon amid the nascent Salazar regime’s increasing authoritarianism.

Pessoa’s most original work, The Book of Disquiet, is a gathering of disconnected ruminations he wrote over more than two decades and left unpublished in a steamer trunk. “This book is the autobiography of someone who never existed,” said Pessoa, writing as Vicente Guedes, one of his many “heteronyms”—fictitious personalities who spoke through him. At various times, Pessoa used more than seventy of these heteronyms in his writing, providing many of them with a distinct backstory.

You can think of them as adult imaginary friends, said Richard Zenith, a leading Pessoa translator and critic who also spoke at the 2019 DIS/QUIET program. The heteronyms, he said, are a mode of self-expression and self-expansion. “They are beings with a sort-of-life-of-their-own,” wrote Pessoa as himself, “and opinions I do not accept. While their writings are not mine, they do also happen to be mine.”

Eliot’s J. Alfred Prufrock comes to mind as a parallel, expressing a related sense of self-alienation. Insistently paradoxical, self-abnegating non-affirmation characterizes The Book of Disquiet: “I am the ruins of buildings that were never more than ruins that someone, in the midst of building them, grew tired of even wanting to build.” Even to regard this as an attitude seems overly affirmative. “Anything that involves action, be it war or reasoning is false, and anything that involves abdication is false too. If only I knew how not to act and how not to abdicate from action either!”

Seldom does an exclamation point exclaim with greater indifference. For a writer whose writing abjures personality, seeming almost to flee in fear of it—and in this way, ironically, attains its distinction—it’s marvelously apropos that pessoa is the Portuguese word for person. “My scorn for everything is so great that I despise myself; for since I despise other people’s suffering, I also despise my own, and thus I crush my own suffering beneath the weight of my disdain.”

Despite such grandiloquent misanthropy, something that sounds almost like civic pride, if not happiness, radiates on occasion from The Book of Disquiet—usually in passages observing the sun and sky, rain and clouds. “Nothing in the countryside or in nature can give me anything to equal the ragged majesty of the calm moonlit city seen from Graca or São Pedro de Alcântara. For me no flowers can match the endlessly varied colors of Lisbon in the sunlight.”

Frequently compared to San Francisco as a seaport city of hills, vistas, morning fog, and streetcars, Lisbon is a changeable presence in The Book of Disquiet, often vividly rendered. This becomes more apparent in the book’s second phase, begun in 1929, when Bernardo Soares, a different heteronym, still pungently embittered if more connected to worldly reality, takes over from Guedes:

The trams growl and clang around the edges of the square, like large, yellow, mobile matchboxes, into which a child has stuck a spent match at an angle to act as a mast; as they set off they emit a loud, iron-hard whistle. The pigeons wandering about around the central statue are like dark, ever-shifting crumbs at the mercy of a scattering wind.

While writing a trunk-full of pages that didn’t see print until well after his death, Pessoa made a living translating business documents. His flair with words in this professional capacity led to an interesting run-in with the puritanism of the Salazar administration. In 1927, the owner of the business Pessoa worked for acquired exclusive rights to market Coca-Cola in Portugal and asked Pessoa to come up with an advertising slogan.

The story is dramatized in a French short movie with a fado soundtrack, “How Fernando Pessoa Saved Portugal.” Long before the English-speaking world learned that “Things go better with Coke,” Pessoa arrived at Primeiro estranha-se, depois entranha-se. Literally, “First you’re estranged, then you’re entranced.” More idiomatically, “At first you don’t like it, then it possesses you”—an idea, as Lisbon’s Minister of Health noticed, that sounds like addiction. The result: Coca-Cola was banned from Portugal, which then remained until 1977—after the return of democracy—the only European country where you couldn’t enjoy “the pause that refreshes.”

A more serious intersection between Pessoa and Salazar-ist authorities occurred during the last months of his life. About politics in general, Pessoa the Lisbon citizen maintained a stance largely consistent with his Disquiet heteronyms, Guedes and Soares: indifference to worldly affairs in the manner of Oscar Wilde’s “art for art’s sake” credo. In The Book of Disquiet, politics and current events aren’t merely unmentioned, they’re scorned: “All revolutionaries are as stupid as all reformers.”

Nevertheless, friction developed between Pessoa and Salazar’s New State (Estado Novo). The sticking point was censorship. Strict laws instituted in 1926 required fado lyrics to be approved before being sung in public, reducing the social content of fado to a whimper. Likewise newspaper and magazine articles were subject to pre-screening and several Lisbon publications were shut down.

Pessoa was paying attention, and over his last few years scribbled extensive unpublished notes on Salazar as documented by University of Lisbon historian José Barreto. Though initially accepting, if never enthused, Pessoa arrived in February 1935 at a personal critical mass. Moved as much by anti-Catholicism as curtailments on free speech, the trigger was a bill in the National Assembly, promoted by the Catholic Church and Salazar, to ban Freemasonry in Portugal.

With an inflammatory article in one of Lisbon’s daily papers, Diario de Lisboa, Pessoa left no doubt of his stance not only against state-sanctioned Catholicism but also more broadly—as an unpublished note makes plain—in support of “Man’s dignity and freedom of Mind everywhere in the world.” The Salazar-promoted merger of religion with the state had brought Pessoa to the limits of his aestheticist elitism and forced a deep-seated democratic idealism into the open.

As Barreto observes, the government had been aiming to enlist Pessoa’s intellectual prestige on its side. The state ministry of propaganda (set up in September 1933, six months after Goebbels organized Germany’s Reich ministry of propaganda) had recently given him an award for his poem “Message,” which draws on the faded glory of Portuguese sea-faring and empire to limn a vision of Portugal as a world-leading nation. Probably for that reason, although without explanation, his article wasn’t censored. Titled “Secret Associations,” it ran in a special, sold-out edition of Diario de Lisboa and, at a time of rare open debate about government, had a huge impact.

“I’ve manufactured a bomb for the first time in my life,” wrote Pessoa in another unpublished note, indulging a rare tone of self-satisfaction. After the newspaper special edition appeared, a cultural weekly, O Diablo, one of few remaining public voices of democratic opposition, paid silent tribute by printing Pessoa’s photo on its front page.

In its official newspaper the government ridiculed Pessoa—even though they’d praised him a few days before. “This is what we get when we trust poets.” Articles Pessoa wrote to further explain himself were censored, and he lived the last months of his life feeling he’d been silenced. His writing from that point on became actively hostile to Salazar.

Saramago Looks Back

Forty-nine years later, in the ominous year of Orwell’s title, Pessoa came back to life. With The Year of the Death of Ricardo Reis, José Saramago created a rich, historical tapestry of Lisbon in the 1930s, embedded in the sweep of European events, lurching toward fascism. His novel inscribes Pessoa himself, along with one of his main heteronyms, Ricardo Reis, as fictional characters.

Forty-nine years later, in the ominous year of Orwell’s title, Pessoa came back to life. With The Year of the Death of Ricardo Reis, José Saramago created a rich, historical tapestry of Lisbon in the 1930s, embedded in the sweep of European events, lurching toward fascism. His novel inscribes Pessoa himself, along with one of his main heteronyms, Ricardo Reis, as fictional characters.

By the time this novel was published in 1984, Portugal’s “Carnation Revolution” of the 1970s had displaced Salazar’s authoritarian regime. Looking back almost fifty years, the novel tracks European events of 1936, such as the outbreak of Spain’s civil war and Italy’s invasion of Abyssinia (now Ethiopia). It is a ghost story and a tale of befuddled romance as well as historical fiction.

Fundamentally, the novel is intertextually rooted in the writing and literary status of Pessoa: The central character, a medical doctor, returns to Lisbon from many years in Brazil to visit the grave of Pessoa the fictional character. Pessoa, whose funeral occurred before Reis arrives in Lisbon (so as a presence in the novel is an unexplained lingering spirit), appears at will to converse with and sometimes annoy his friend. As readers we know, though the character Reis does not, that he’s a Pessoa invention, doomed to non-being with the author’s passing. In his visits, which occur unannounced and unpredictably, Pessoa seems to goad Reis to question his existence. As Reis (or is it Pessoa?) puts it during their first conversation, “None of us is truly alive or truly dead.”

Within this unusual narrative framework and with an ironic sensibility fitting with fado and The Book of Disquiet, Saramago builds an epic comic satire. Among his targets: middle-class mannerisms, conservative Catholicism, police-state surveillance and 20th-century European fascism. In day and night, rain and sun, Reis wanders Lisbon’s streets, its harbor and neighborhoods, which Saramago renders evocatively.

In a Kafka-esque sub-plot that drives the narrative, Reis out of nowhere receives a police writ requiring him to report for interrogation. As he arrives at police headquarters, he’s perplexed:

They send him up to the second floor, and up he goes, holding the writ like a lamp before him, without it he would not know where to put his feet. This document is a sentence that cannot be read, and he is an illiterate sent to the executioner bearing the message, Chop off my head. The illiterate may go singing, because the day has dawned in glory. Nature, too, is unable to read. When the ax separates the head from his trunk the stars will fall, too late.

His questioning proceeds with understated foreboding—a scene that extends over pages and echoes Raskolnikov’s encounter with his detective inquisitor in Crime and Punishment. As he leaves the station, Reis gains surveillance by a stooge named Victor whose presence is always signaled by the reek of his onion breath.

Saramago’s tone throughout is as if society’s drift toward fascism is a comic opera that will play out because people are occupied with their love affairs and gossip and poets with convincing themselves of the greatness of their verse. Literary critic James Wood praised the tone of Saramago’s fiction “because he narrates his novels as if he were someone both wise and ignorant.”

Gradually, the story advances toward a stadium rally for Salazar’s New State. Reis, in a fog of disappointed romance, caught in the flow of people and events, finds himself among the stadium throng. A speaker proclaims the urgency of the need for a national militia; the crowd roars approval. All that remains is to decide shirt color. Realization sets in that black (Mussolini’s Italy), brown (Hitler’s Germany), and blue (Franco’s Spain) are taken. What’s left?

Enough. Let me not reveal too much of this fascinating novel, in which one feels connection to Latin America’s “magical realism” and the meta-fictions of Jorge Luis Borges. The Year of the Death of Ricardo Reis evokes not only a perilous period of European history that calls out for wariness in 2019 America, but also many moods of an enduringly beautiful city.

Differently from but with parallels to Pessoa in 1935, Saramago eventually pushed the limits of official tolerance. Politically far left, he leaned toward anarchism and was critical of the Catholic Church, the European Union, and the International Monetary Fund. His controversial 1991 novel, The Gospel According to Jesus Christ, reinterpreted the New Testament as an indictment of God. Government disapproval of this work led him to voluntary exile in the Canary Islands for his last twenty years.

Saramago—who, like Pessoa, was not well known outside the Portuguese-speaking world—won the 1998 Nobel Prize in Literature, which cited him as a writer “who with parables sustained by imagination, compassion and irony continually enables us once again to apprehend an elusory reality.” Saramago died in 2010, but not before prominent literary critic Harold Bloom in 2003 dubbed him “the most gifted novelist alive in the world today.”

* * * *

Notes

Sources include: Simon Broughton, “Secret history,” New StatesmanAmerica (Oct. 11, 2007); José Barreto, “Salazar and the New State in the writings of Fernando Pessoa,” Portuguese Studies 24 (2): 169 (2008); Adam Kirsch, “Fernando Pessoa’s Disappearing Act,” The New Yorker (Aug. 28, 2017); “Fado: Portuguese Soul Music,” The Forum, BBC News, World Service (May 5, 2019).

BBC fado program: https://www.bbc.co.uk/programmes/w3csyp4m

DIS/QUIET Literary Program: http://disquietinternational.org/.

Quotations from The Book of Disquiet are from Margaret Jull Costa’s 2017 translation.

Quotations from The Year of the Death of Ricardo Reis are from José Saramago, The Year of the Death of Ricardo Reis, translated by Giovanni Pontiero (New York: Harvest, 1992).

* * * *

Mike Schneider, who won the 2016 Robert Phillips Prize in Poetry from Texas Review Press, attended the DIS/QUIET International Literary Program in Lisbon, June 23 to July 5, 2019.

Volumes One Through Five

Volumes One Through Five interviewed by bart plantenga

interviewed by bart plantenga