Interviewed by Jorge Armenteros

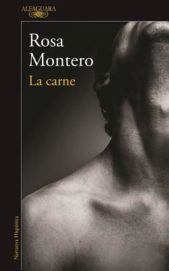

The repercussion of the work of Rosa Montero in the world of International Hispanism is enormous. Ten books, thirty doctoral theses, and more than 120 academic papers have analyzed her work. In 1978 she won the World Interview Prize, in 1980 the National Journalism Prize, and in 2005 the Madrid Press Association Award. This year she has received the Professional Career Award awarded by the International Club of Prensay and the Manuel Alcántara International Journalism Prize from the University of Málaga.

Two of her novels, The Lunatic of the House (2003) and Story of the Transparent King (2005) received Spain's top book award, the Qué Leer Prize. Her other titles include the short-story collection Lovers and Enemies and the novels Beautiful and Dark, My Beloved Boss, and The Heart of the Tartar. Her work is translated into more than twenty languages.

Montero has been a visiting professor at Wellesley College, Boston and at the University of Virginia. She has taught creative writing at Bingham Young University, Utah, and Miami Dade College, Miami, and received a scholarship to lecture at Queen's University in Belfast, UK. Montero has taught literature and journalism in the School of Letters and the Contemporary School of Humanities, both in Madrid.

This interview was conducted verbally this past spring in Madrid, Spain. We met in her apartment, which overlooks el Parque del Retiro; surrounded by a multitude of sculptures, paintings, drawings, and amulets of salamanders, we spoke about literature and her last published book, La Carne (Alfaguara, 2016). I later transcribed the interview and edited the content for length and accuracy. Once edited, I translated the interview from Spanish into English.

Jorge Armenteros: At the beginning of La Carne, we find the subject of age. We know Soledad is on the brink of her sixtieth birthday—“Dogs’ age,” as you describe it in the book. What motivated you to choose her as the main character?

Rosa Montero: The truth is you do not choose the stories you tell, but stories choose you. You do not choose, therefore, characters either. Novels are like dreams you dream with your eyes open; they are books which appear in your head with the same apparent immediateness as they appear in your dreams at night. A writer always writes their obsessions and the truth is that all throughout life we end up writing the same thing in different ways. I am a tremendously existentialist writer; a contemporary novel is a novel that is very much marked by death, but mine is even more than the average one. Then all my books speak in a very obsessive way about death and the passing of time and what the time does to us or undoes to us, because our lives mean us being undone over time.

Rosa Montero: The truth is you do not choose the stories you tell, but stories choose you. You do not choose, therefore, characters either. Novels are like dreams you dream with your eyes open; they are books which appear in your head with the same apparent immediateness as they appear in your dreams at night. A writer always writes their obsessions and the truth is that all throughout life we end up writing the same thing in different ways. I am a tremendously existentialist writer; a contemporary novel is a novel that is very much marked by death, but mine is even more than the average one. Then all my books speak in a very obsessive way about death and the passing of time and what the time does to us or undoes to us, because our lives mean us being undone over time.

So it was natural that Soledad came out of nowhere. I mean, it is not that I chose her. On the other hand, Soledad has a feature I did look for. There was a conscious thing I wanted to find in her, and it is that I wanted to write a very extreme character who was close to turning sixty and who had never had a stable loving relationship. Soledad has had many lovers, but she has never had a complete everyday sentimental story. When we read the novel, we understand why: she has reasons for not having lived it. I wanted to write such an extreme character, because I wanted to ask myself how it is that someone, upon reaching that age, with such a life, can, perhaps, start to say to herself, “I will die without getting to know love,” and I wanted to do some research, I wanted myself to live within a life like that one to see how it feels, and what kind of wound can do that to you in life. But take into account that when I was already working on this character, I realized that it would not have been necessary to go so far, because I understood that there are lots of men and women who have been married for twenty years, or who have married and separated and remarried three times, and who, nevertheless, share the same experience with Soledad, because they feel they have never been loved the way they wanted to be loved. This might become such a deep wound that it destroys their life, that creates in them a radical frustration and that makes them feel they have thrown their lives away. And, in some cases, they might have gotten to this point due to bad luck. But in other cases, I think it is because we do not know how to live, which is another of the themes of the novel La Carne. We, humans, make out of our lives nonsense very often. There is a phrase from Oscar Wilde I love that says, “For most of us, real life is the life we do not lead.” Tremendous, isn’t it? Tremendous, but very truthful.

JA: There’s the following passage in the book: “Because one of the most widespread mirages is to think we are not going to be like the other old people, we will be different. But, then, age always catches you and you end up being equally shaky, unstable and drooling.” Would Soledad be able to overcome this overwhelming reality?

RM: No, absolutely, never, and nobody can. And, besides, we all believe it. As you grow old, you go telling yourself, “But not me.” You go challenging others if you are lucky, and if you are still physically fit and continue to look younger. I myself believe it, because I see people my age who look much worse, but it is not true. At any given time, if you live long enough, old age catches you . . . the only choices we have in life are either the impairment of old age or early death.

JA: Flesh and senses seem to enact guidelines in Soledad’s life. “Tyrant flesh enslaved everybody,” says the narrator of the novel. Is that just Soledad’s struggle, or do you propose it to be our struggle as well?

RM: No, no, of course, it is everyone's struggle. The relationship between the human being and the flesh has always been a matter of huge conflict. Since the beginning of time every religion has tried to take control of our selves, usually from a repressive point of view, most often than not inhibiting the body as well. Other times, on the other hand, as in certain eastern liturgies, empowering the body and doing away with the ego. But living inside this body never ceases to be a conflict. We are cultural beings and that clashes with our animal instincts. That’s where the title comes from. One day I came up with the title and I thought, what a title—so simple, so easy, so powerful, so telling. How is it that there aren’t twenty thousand novels titled La Carne? But there aren’t. So I kept my mouth shut, desiring at all costs not to have it stolen, until my book came out. In the first place, the flesh is what traps us, because no one has ever chosen his or her body to live in, has he? You are what you are and you didn’t get to choose it. It’s the flesh that traps us in the first place, the flesh that makes us sick, that makes us old and that eventually ends up killing us. But at the same time, it’s that glorious flesh that enables us to scratch heaven through sensuality, through sex, through passion. Paradoxically, the flesh that kills us will also make us feel eternal for a brief moment because that’s what we are in passion, eternal—we abandon ourselves, we merge, we give ourselves to the other, so much that when we are loving passionately, death doesn’t exist.

JA: Do you think Soledad truly loves Adam or does she only desire him, even though she is convinced otherwise?

RM: No, she is trying to convince herself of only wanting him, but what she truly is looking for is love. In fact, almost at the beginning, when she is about to call him on the phone, their relationship hasn’t even begun and she says: “More than a lover, I want a loved one.” She is afraid of herself, of that need for total love she has, of her loving passion. She has kept it under control for so long with all of her lovers and suddenly, with Adam, it just goes off.

JA: Soledad shares with Adam the frailty of those who have suffered, but that communion is not enough to keep them together. Is that the book’s central tragedy?

RM: No, truthfully, no. Because they are an impossible couple in so many ways. Let’s go back to the novel’s beginning. She is an exposition commissary, an educated woman, intellectual, nearing her sixty years, who’s had a lot of lovers, as we’ve established, but no serious significant others, who just broke up with one and who, in a final childish outburst, because love turns us into children, has no other brilliant idea than to try to make her ex-lover jealous in an opera performance, so she hires an extremely handsome gigolo. She doesn’t want to have sex with the gigolo, which she could, since he’s a prostitute; what she wants is to have that hottie by her side and make the other guy jealous. But we already know that us human beings spend life making plans and then reality comes along and tears them down in a single second, so there’s a violent and unexpected event that disrupts everything and they initiate a relationship. So, all the way from the beginning, it’s a wrong relationship. There’s a huge age difference and, besides, he’s a prostitute. That makes the relationship far more ambiguous than it already is. What’s really important in the novel is the edification of the mirror, the twins, the other one. She, the main character, has a twin. He, Adam, also has a twin. They are both like twins, one being a mirror to the other one. I believe in twinship—in my novels there’s lots of twins—and it’s exactly about that. It’s about all of the possibilities of our own being that we leave behind because one of the things that troubles me the most in life, that upsets all of us, is that we reach this world with the capability to be anything. But then life starts to confine us inside our small realities. And then, the shadow of those other possible lives stays to lurk us, which also sticks to you and you can’t shake it off, since it was so easy, it’d have been so easy to lead another life. We make twenty thousand small choices a day, and maybe one of those choices is the one that will take us to a completely different life. If you stop to think about it, it is vertiginous, hypnotizing and distressing. So, twins represent the other possible lives you could have led, which you drag behind you some way, in a ghostly way.

RM: No, truthfully, no. Because they are an impossible couple in so many ways. Let’s go back to the novel’s beginning. She is an exposition commissary, an educated woman, intellectual, nearing her sixty years, who’s had a lot of lovers, as we’ve established, but no serious significant others, who just broke up with one and who, in a final childish outburst, because love turns us into children, has no other brilliant idea than to try to make her ex-lover jealous in an opera performance, so she hires an extremely handsome gigolo. She doesn’t want to have sex with the gigolo, which she could, since he’s a prostitute; what she wants is to have that hottie by her side and make the other guy jealous. But we already know that us human beings spend life making plans and then reality comes along and tears them down in a single second, so there’s a violent and unexpected event that disrupts everything and they initiate a relationship. So, all the way from the beginning, it’s a wrong relationship. There’s a huge age difference and, besides, he’s a prostitute. That makes the relationship far more ambiguous than it already is. What’s really important in the novel is the edification of the mirror, the twins, the other one. She, the main character, has a twin. He, Adam, also has a twin. They are both like twins, one being a mirror to the other one. I believe in twinship—in my novels there’s lots of twins—and it’s exactly about that. It’s about all of the possibilities of our own being that we leave behind because one of the things that troubles me the most in life, that upsets all of us, is that we reach this world with the capability to be anything. But then life starts to confine us inside our small realities. And then, the shadow of those other possible lives stays to lurk us, which also sticks to you and you can’t shake it off, since it was so easy, it’d have been so easy to lead another life. We make twenty thousand small choices a day, and maybe one of those choices is the one that will take us to a completely different life. If you stop to think about it, it is vertiginous, hypnotizing and distressing. So, twins represent the other possible lives you could have led, which you drag behind you some way, in a ghostly way.

JA: The chase topic is important in the novel.

RM: Yes, it’s a novel of pursuit. I think Soledad is chased by her ghosts; she is certainly running away from her childhood. She has a very tough childhood and there are several terrors chasing her, such as the terror of going crazy, because she has a schizophrenic sister. Therefore, Soledad is constantly running away. That chasing could be self-destructive, but there is a redemption moment in the novel, a moment in which she forgives another person and she forgives herself, and that is going to let her end the book in a better situation. It’s not a happy ending, but it’s a much less desperate place than in the beginning of the novel.

JA: Do you think destiny is a tragedy or a chance to vindicate ourselves at the end of our lives?

RM: Well, it depends on what we consider destiny. Because if we consider destiny as closed, as they do in the East, then it would be a tragedy. Me, I belong to a Western tradition and I am strongly proactive, I think we can always do something. It’s true that a human being cannot control what happens to him. I can leave here now and a truck runs over me: I can’t control it. However, what we can control is how we respond to what happens to us, what we do with what happens to us. Even if the range of choice is minimal, there is always a choice. For example, in the Nazi concentration camps we have records and we know there were prisoners, poor men, that betrayed their mates—I insist they were victims, I’m not going to judge them—and on the other side, in the same circumstances, there were absolutely heroic prisoners who helped their mates. Even in that tiny little range of choice, you can choose. So, from that point of view, destiny is our battlefield. It’s not a tragedy; it is what we do with it.

JA: You appear in the novel as Rosa Montero, with tattoos and everything. Do you write like that, just like the book’s Rosa Montero explains, embodying the lives of all your characters?

RM: Totally. That thing about appearing, I don’t find it so pleasing. I have the feeling . . . no, the conviction, the certainness that reality and fiction are really mixed up. The frontier between reality and fiction is tremendously porous and slippery. And in fact, when I remember something that has happened to me a long time ago, let’s say twenty years ago, many times I’m not sure if I have actually lived what I am recalling, or I have dreamed about it, or I have written about it, or I have imagined it all. And the four possibilities have the same experiential force to me. That’s why there’s this game in many of my novels, in this border area between reality and fiction. Ana Santos Aramburo, who is actually the National Library Director, appears in La Carne. Moreover, she’s a friend of mine and the poor woman didn’t know I was putting her in a novel, so when I finished the first draft, I sent it to her and I told her: “Ana, look, you’re appearing there and you also talk a lot, so take a look at it and see if you’re OK with that.” Thank goodness she was! So, including myself in the action is also within this game. And the truth is I had a lot of fun looking at myself through the eyes of my character, because it’s me. And Soledad is right when she criticizes me. Yes, of course, I am a lot like Peter Pan. It’s true, I wear Doctor Martens boots, I have tattoos and I am dressed with young clothes . . . everything she says is true, it’s just that I’m not uncomfortable at all with that. Kids are the ones who create; I find it really great to have my inner child still alive. But besides this chapter, besides playing with the limits of reality and fantasy, it’s a key for the novel’s structure, because there I tell my character that imaginary life is also life, and that too helps my character to end the novel better than how it started.

JA: In what way does your journalism career influence in your fiction writing?

RM: You can’t make a living out of fiction writing. You can’t and you shouldn’t. I always tell everyone that is a huge mistake, because I have seen many writers get lost because of that. Novels should be an area of total freedom. It is already difficult to fight against the market pressure, against the pressure from your friends, your family, your editors, against the pressure of your own ambitions. All of that is already a fight. If you also have to earn money to pay for the mortgage, it’s fatal. I have seen how friends of mine, very good writers, who have left their jobs to make a living out of their books, started publishing every year really bad books, because they needed to get an advance payment. And they have been shot to shit—in very few years they have disappeared as writers. Incredible, right? I think you always need to have another job. I make a living out of being a journalist. The print journalism I do, reporting, is a literary genre as any other, and it can also be as sublime as any other. For example, In Cold Blood, written by Truman Capote, is a spectacular book. I like journalism very much as a job. And I have learned a lot, really a lot . . . I have met many worlds, and not only geographic, but also inner worlds. But it is always a job, it belongs to my outer being, to my social being, hence I may get tired of it. I’ve been working as a journalist, now I keep working as an article writer, for more than forty years.

Fiction, however, is a different matter. Like many novelists, I started writing when I was a little girl, a very little girl. My first tales, I wrote them when I was five years old and they were about little rats that talked. My mother dated them and I have them around here. Since then, I’ve been writing fiction for as long as I can remember myself as a person. For me, fiction belongs to my inner being, is something essential which defines me—I am a fiction writer in the same way I am a woman, the same way I am dark-haired—it is something essential and structural. It’s like an exogenous skeleton that keeps me going. And I don’t know how I would manage to live without writing, working with words. But they are two extremely opposite genres; let’s say as essays are to poetry. In particular, within journalism, clearness is a value. The clearer and less misleading a work of journalism is, the better. In a novel, ambiguity is a value. The more readings a novel has, even contradictory, the better. In journalism, you talk about what you know; you have provided yourself with records, you have gathered information, you have performed interviews. In a novel, you talk about what you don’t know, because the novel comes from the unconscious. They are very different relationships with words and with the world. In journalism, you talk about trees; in the novel, you try to talk about the forest.

JA: Who are the American contemporary novelists you find interesting to read?

RM: Well, the United States is still the empire, so we read a great many American authors: Jonathan Franzen, Lucia Berlin, Paul Auster . . . Many. I will say there are two authors I consider my teachers, one on the most realistic side and the other one in the most fantastic side: one of them is American—Ursula K. Le Guin, who’s still alive, in Portland—and the other one is half American, Nabokov, although his Russian ancestry and his Russian works also influence me a lot.

JA: You have written many novels and you have won many prizes. Which aspects of your narrative do you aim to develop in your next books?

RM: The art path leads you to be increasingly free. That’s what you do. Maturity happens because of being increasingly free. And what does “because of being increasingly free” mean? Well, Julio Ramón Ribeyro, the Peruvian writer, used to say a mature novel demands the author’s death, not literal death but metaphoric death, which is the author has to truly erase himself. Therefore, to be truly free, you have to break free from internal and external pressures. The things that restrict the freedom of writing are thousands, from the fear of hurting someone to the will of pleasing someone . . . a lot of things. And you actually have to erase the self completely and become a sort of medium, let the story pass through yourself and let the story dance with you. For example, all my life I have been saying, and it’s a good advice for young authors, that you have to find the balance between self-criticism and arrogance. I mean, you have to fiercely criticize your own work, tell yourself “Oh, this is really bad. I am failing at this,” but at the same time, in order to not get blocked, you have to be confident enough in yourself to say: “OK, but next time I’ll do better and someday I will write the best novel ever written.” You must have this as a lighthouse, but when you’re already getting to a certain age, like me, for example, and you become a mature author, you have to lose even that, you have to lose even the ambition of writing a wonderful piece of work. You have to lose everything. You have to erase yourself.

JA: You’re talking about a complete, absolute freedom.

RM: Yes, yes, that’s right, and I’m following that path and now I’m also, I think, in the plenitude stage of my writing. I feel very close to that, I am increasingly free. I have written La Carne with a huge freedom. By being completely free, totally erasing the self, you can dance well, you can make love well, and you can write well.

JA: And with that spirit, are you working on any new project?

RM: Yes, now I’m going to make a third novel about my character Bruna Husky, whom I adore. This is the closest character, although she’s an android from the 22nd century, but she’s the character I feel the closest to. It’s a character I feel really close to, that I like a lot, and I’m going to write another novel about her. There are already two of them, which are Lágrimas en la lluvia (Tears in Rain) and El peso del corazón (Weight of the Heart), and I have a lot of notes about the third one.

Click here to purchase La Carne at your local independent bookstore

Click here to purchase Beautiful and Dark at your local independent bookstore

Anna Leahy

Anna Leahy