Interviewed by Allan Vorda

Madison Smartt Bell was born and raised in Nashville, Tennessee, and graduated from Princeton University. He has published a total of twenty-two books, more than half of them novels. He is perhaps best known for his trilogy of historical fiction works focusing on Toussaint Louverture and the Haitian Revolution; All Souls Rising, the first of the trilogy, was a finalist for the National Book Award and the PEN/Faulkner Award, and it ultimately won the Anisfield-Wolf Award for the best book of the year dealing with matters of race. He and his wife, the poet Elizabeth Spires, teach at Goucher College.

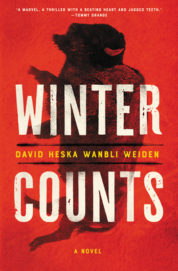

Bell’s latest work, Child of Light: A Biography of Robert Stone (Doubleday, $35), reflects his lifelong love of the work of that novelist, and inspiration Bell has drawn from Stone and his contemporaries. We discuss the biography in the following conversation, held over email in recent months.

Allan Vorda: You have produced the definitive biography of a great American author. Walk us through the origins of how you got started on this project. Did you have full access to Robert Stone’s manuscripts and letters? Did his widow give you permission to discuss Stone’s alcohol and drug issues, as well as their open marriage?

Madison Smartt Bell: Yes, I had extraordinary support from Janice Stone, and couldn’t have written the book without that. I was good friends with her before Bob’s death but working on the project together deepened that friendship a good deal. At the time of his death, there were twelve crates of papers in the Stones’ New York apartment scheduled to go to a Stone archive at the New York Public Library. Janice delayed sending them so that I could have the convenience of working on the material at her place. (Later I also worked with the Stone archive already housed at NYPL, whose staff was wonderfully helpful.)

Early in the discussions of the biography I called on Janice at the Stones’ house in Key West, and said I needed to know two things: how frank she wanted to be about drugs and about other women. She thought for a bit (Janice has no fear of silence) and said that she wanted the whole truth told and believed that Bob would want the same. Early on I interviewed her a couple times about the early period of Bob’s life and sent her questions by email. Janice eventually responded by writing her own memoir, sending it to me serially; that was an amazing asset to have, as any reader can see from the amount that I quote from it. Gerry Howard, the editor at Doubleday, worried about that; he said, reviewers are going to quip about your having a co-author. I said I don’t mind if they do. It really was a partnership.

Early in the discussions of the biography I called on Janice at the Stones’ house in Key West, and said I needed to know two things: how frank she wanted to be about drugs and about other women. She thought for a bit (Janice has no fear of silence) and said that she wanted the whole truth told and believed that Bob would want the same. Early on I interviewed her a couple times about the early period of Bob’s life and sent her questions by email. Janice eventually responded by writing her own memoir, sending it to me serially; that was an amazing asset to have, as any reader can see from the amount that I quote from it. Gerry Howard, the editor at Doubleday, worried about that; he said, reviewers are going to quip about your having a co-author. I said I don’t mind if they do. It really was a partnership.

I don’t know that I’d choose the term “open marriage,” since it was not really in use before the early ’70s. By then, the Stones had been married more than ten years and had passed through the Kesey orbit. I believe Jane Burton said, “everybody was in love with everybody” and they all expressed that fully. What Janice told me, while Bob was still living, is that they’d agreed to cut each other some slack in that area since they had married so young and then entered the gigantic cultural upheaval of the 1960s; she felt that this leeway made it possible for them to stay together, which is what they both wanted. You might say that their arrangement prefigured the open marriage trend, but I wouldn’t say it was part of it.

AV: Can you briefly describe Stone’s upbringing regarding his mother, his Catholic education, and his joining the Navy?

MSB: Gladys Grant was a single mother, so single that Bob never knew his father; nothing is known of Homer Stone beyond the name on Bob’s birth certificate. In Bob’s early childhood Gladys maintained them fairly comfortably on what she earned as a school-teacher. But she lost that job, probably thanks to mental illness, and that early stability went with it. Still a small boy, Bob spent a few good years as a boarder at St. Anne’s School on Lexington Avenue in Manhattan, a school run by Marists which took in supernumerary children from large Catholic families. Bob was a student there through high school, and was in and out as a boarder for several years, but more in than out during his young boyhood. Gladys next tried to move them to Chicago, where they stayed less than a year. On their return to New York, they were briefly homeless, then shared a single room in various SRO hotels, with Gladys earning money as a maid or by stuffing envelopes.

In his teens Bob had some involvement with a street gang (and also an incipient drinking problem), but he was a good enough student to get a top score on the Regents exam as a senior at Saint Anne’s, and to win a scholarship to NYU. Around the same time, however, Saint Anne’s expelled him for coming to school drunk and (worse) talking a classmate into renouncing Catholicism. Street life in New York was becoming more dangerous; Bob was involved in one fracas where someone was fatally wounded with a knife, and heroin use was becoming more common in this milieu. No doubt he was also ready to get out of his mother’s single room, so he took advantage of a Navy program that allowed a seventeen-year-old to make a three-year enlistment.

AV: Stone met Janice, his future wife, while both were students at NYU. They later dropped out of school, got married, and then moved to New Orleans in January 1960. How did this move affect Stone’s writing and lay the groundwork for Stone’s first novel A Hall of Mirrors?

MSB: Well, first she got pregnant and then they got married. Bob had taken up his NYU scholarship at the end of his Navy enlistment, but he had to be a full-time student to keep it, and he couldn’t sustain that while also working at the Daily News full-time. He’d promised Janice a European tour (having seen a good deal of Europe while in the Navy) and New Orleans was as close to that as they could manage at the time. They got decent jobs as census canvassers at first; Janice having to conceal and work around her pregnancy until she gave birth to the Stones’ eldest. When the census finished, Bob tried factory work, briefly, and sold Bibles in the boonies, briefly and unsuccessfully. Finally, they returned to New York, where Janice could at least get some support from her family.

New Orleans furnished the setting for A Hall of Mirrors—Rheinhardt and Geraldine live in the Stones’ French Quarter apartment (later to be reconstructed as a set for the movie starring Paul Newman). And the Stones got around all over town, what with Bob’s various short-term employments, and most importantly the census work—that took Bob into the Black community, an important factor in the novel.

AV: Would you agree the most momentous event in Stone’s life was being granted a Stegner Fellowship at Stanford? Pretty amazing since he only had a GED certificate and less than three full semesters of college; yet this seemed to help propel him on the road to a writing career.

MSB: It was certainly a life-changing event, especially since Bob had never assumed he would go to college—his childhood produced the expectation that he’d enter the workforce after high school, like most of his peers, although his restlessness opposed that prospect. He would not have applied for the Stegner if not pushed to do it by Mack Rosenthal, an NYU professor who’d seen Stone’s promise from some early stories written for Rosenthal’s class. On the other hand, Stegner had invented the program to serve students who fit Bob’s profile: young men leaving the military after World War II, with incomplete educations and uncertainty about what they could or should do.

A byproduct of Stone’s zigzag path through conventional higher education is that though in maturity he was encyclopedically knowledgeable and immensely well-read, he was also very much an autodidact and so had little traffic with received ideas.

AV: While at Stanford, Stone was working on his manuscript for A Hall of Mirrors, but this is also where he met Ken Kesey. Tell us about his relationship with Kesey—which included taking LSD, being part of the Merry Pranksters, the parties at Perry Lane, and going to Mexico.

MSB: One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest had recently come out when the Stones arrived in California, making Kesey the biggest star to have come out of the Stegner. The Perry Lane scene was a Petri dish for the enormous cultural changes on the way, with free love aplenty and many doors of perception being kicked open by mescaline, psilocybin, and LSD. At the same time, most of the people living there were much like the Stones: young couples trying to take care of babies while also finishing novels or dissertations. Kesey had some gravitational force in the community, but was not yet the quasi-cult leader he would become once he moved up to La Honda.

Bob was extremely enthusiastic about any and all hallucinogens on offer. He and Kesey were good, close, life-long friends, but Bob was always resistant to the cult-building aspect of Kesey’s charisma (and Janice even more so). The sense grew that Bob’s novel would never be finished if the Stones stayed in Kesey’s orbit. The Stones were back in New York by the time the Merry Pranksters moniker was coined. Bob was still working on the novel, in a more disciplined manner than before, when the Prankster bus rolled in for the 1964 World’s Fair. The Stones rode the bus around town with their friends, but they were not really “on the bus” in the cult sense of the phrase.

Kesey fled to Mexico in 1966 to avoid drug charges, taking a handful from his inner circle with him, including Neal Cassady. Bob had finished A Hall of Mirrors, and didn’t yet have a good start on a second novel. He got an assignment from Esquire to write a piece on Kesey’s Mexican camp—unlike most other reporters, Bob knew how to get there. He eventually wrote nearly a hundred pages of a piece which addressed the whole Kesey phenomenon very astutely, but Esquire passed on it. Bob shared the material with Tom Wolfe, and eventually published a much shorter version in The Free You as “The Man Who Turned on the Here.”

AV: Right—Stone wasn’t actually on the Further bus except briefly, when it arrived in New York City, but he had been exposed to Neal Cassady while in Mexico. When I interviewed Stone in 1990, I asked him about Cassady, and he said: “He was a walking cautionary tale about speed. If you wanted to think of one hundred reasons not to take speed, then Cassady could provide you with at least eighty of them.” Can you add any other insights about Cassady?

MSB: That’s a great line about Cassady. I don’t think I can top it. I never knew the guy and he has been well mythologized by other writers. Bob did once tell me that Cassady had achieved a sort of immortality in the form of his parrot, who could say a lot of Cassady dialogue in a perfect impression of Cassady’s voice, and who may still be doing it somewhere, given the longevity of parrots.

AV: If getting the Stegner fellowship was not the most important, life-altering event in Stone’s life, then working as a journalist in Vietnam had to be right up there. Stone stated: “I realized if I wanted to be a ‘definer’ of the American condition, I would have to go to Vietnam. In many ways it changed my life.”

MSB: Bob went to Vietnam from London, where the Stones had been living for quite a while, increasingly cut off from the American scene. Bob was struggling with a second novel set in the U.S. He agonized terribly about making the trip, but he was so stuck in the novel that in the end he felt he had to go. Getting killed in Vietnam would be no worse than atrophying in London. He spent most of his time with the fringier Anglophone journalists in Saigon, but he did manage to come under fire once and that was certainly a key experience—one that he gives to John Converse, a protagonist of Dog Soldiers.

I think that before the trip he had a suspicion that Vietnam was such a key factor in the American experience at the time that you couldn’t write anything that didn’t somehow include it—Dog Soldiers is the expression of that idea. Vietnam is omnipresent in the novel, though mostly offstage.

AV: Stone was given a teaching position at Princeton (despite having no college degree) where he slowly churned out the manuscript for his second novel. It is amazing to think he didn’t know what he was doing when he began writing Dog Soldiers, since it is one of the great American novels of the twentieth century, but this is what Stone said about writing the book that would win him the National Book Award: “I didn’t really research it. I didn’t know what I was doing when I began it.”

MSB: Princeton had one of the first undergraduate creative writing programs in the country (one reason I went there a few years later). Bob got on board at a moment where the main qualification to teach in that field was achievement in the craft as proven by publication and recognition; degrees didn’t matter so much.

My sense is that he was unable to get any real start on Dog Soldiers before going to Vietnam; he was, among many other things, a great procrastinator, but I also think that he began with a very inchoate sense of what he wanted to do, and that his Vietnam experience somehow unlocked the problem for him.

AV: Do you think Ray Hicks in Dog Soldiers was based on Neal Cassady—and, if so, in what ways?

MSB: Not much, although Hicks’ Zen death march scene is probably inspired by Cassady’s having died while walking a Mexican railroad track in 1968. Hicks isn’t a speed freak (speed was one of the few drugs that didn’t much appeal to Bob recreationally, although he did sometimes take Ritalin to write), and he doesn’t have Cassady’s manic, non-stop-jabbering personality.

I think, rather, that Bob did here what he often did: split aspects of his own personality to create two separate characters for a story, which in some ways opposes them to each other. Hicks is what Bob might have become if he hadn’t married, had gone from the Navy into the merchant marine (he had a brief encounter with the latter at the end of the New Orleans stay) and drifted into a life a few steps outside the law. Hicks is a man of action, not entirely unreflective but far less reflective than Converse, who’s a writer with problems completing his work, who shares much of Bob’s ironical insight, and whose ability to imagine the worst that can happen makes him far more timorous than Hicks.

AV: Fans of Robert Stone probably wish he had written more novels. It seems Stone would always procrastinate while writing, and he even referred to himself as a “slothful perfectionist.” What are your thoughts on Stone’s productivity?

MSB: It’s a very solid body of work, and I think one of Bob’s novels is worth three or four of most of his contemporaries’. We occasionally talked about a difference between him and me: I write with facility and have a good time doing it. For me, it’s almost never not fun. For Bob the writing was often a painful experience, especially in later stages when he would push himself further than most of us do, to make every scene and every sentence diamond-hard. Completing each of his best novels was a more taxing experience for him than it is for most of us, so he might not have been quite as eager to turn around and do it again as the average novelist. It’s also true that he was very amenable to distraction and inclined to be a rolling Stone in the gathers-no-moss sense.

AV: In Child of Light you write, “In the summer of 1983, my mother handed me a paperback copy of A Flag for Sunrise. We were on our way to spend a few weeks with friends in the Roman Campagna and a couple of other places. It was my first trip to Europe; my first novel had been published a few months earlier. Before I got on the plane, I had never heard of Robert Stone. By the time the wheels touched down in Rome, he was the writer I wished I could become.” What other recollections can you share about being captivated with Stone’s work and how it affected your own writing career, which has now spawned twenty-two books?

MSB: Stone is one of the few contemporary writers (along with Cormac McCarthy, Mary Gaitskill, William Vollmann, and Eudora Welty) that I can read many times over and still get more out of it. And I’ve read the great Stone novels so many times I’m sure I just internalized them, and at that point one stops being aware of the influence. I think there’s some bleed of Stone’s style into mine, although not so much that many people have noticed.

During the years of our friendship, Bob was very admiring of my work, particularly the Haitian novels, which was nice but also felt a little weird; I’d be thinking, “you’re 2.5 times the writer I’ll ever be—what are you talking about?” I mean, I don’t take a back seat to practically anybody, but to Stone I do. I think maybe the fact that I did it easily impressed him, perhaps excessively, and surely more than it does me—it’s lucky in a way, but I don’t consider it a virtue.

AV: There is an interesting and sublime metaphor in A Flag for Sunrise when Holliwell is scuba diving; fear overtakes him as he imagines he is being watched by something unseen, probably a shark. The symbol of fear is also evident when Heath declares, “I’m the shark on the bottom of the lagoon. You have to sink a long way before you get to me. When you do, I’m waiting.” It seems that fear was ingrained in Stone’s consciousness on the day he went out on patrol in Vietnam. How do you think fear drove Stone in both his life and his writing?

MSB: Proverbially, it’s easier to be brave if you’re stupid—or maybe unimaginative would be a better word. Active imaginations project bad outcomes, which are hard for courage to overcome, and sometimes those outcomes materialize. I think Stone’s experience under fire was not symbolic at all, but a primal, visceral experience, a self-annihilating nadir he was always aware of afterward.

AV: Pablo Tabor from A Flag for Sunrise is a scary character for me as a reader. Every time a passage occurred with his name, my antenna came up anticipating some horrific act of violence. Pablo has been referred to as an “institutional personality” and as an “affectless sociopath”; he’s certainly one of Stone’s most fascinating characters. I wonder if you see any similarities between him and Ray Hicks.

MSB: I think both are in some ways there-but-for-the-grace-of-whatever self-portraits. Bob had a very evolved idea of the institutional person as someone whose character, in the absence of much in the way of parenting, is shaped by orphanages, juvey, prison, and the military. His childhood and youth gave him the opportunity to become that person, but he didn’t. Pablo did.

AV: Stone had a lifelong battle with religion and the existence of God, nurtured early on due to harsh Catholic school discipline, against which he rebelled, eventually being expelled due to being “militantly atheistic.” As you note, Stone seems to espouse various philosophical concepts, including atheism, Heidegger, and even psychedelic mystical beliefs. This struggle seemed to weigh heavily on him as he was older and nearing death. How do you view Stone’s concept of religion?

MSB: He told some interviewer somewhere that you can’t stop being Catholic any more than you can stop being Black. He also wasn’t always fighting Catholicism; he had a period of intense devotion in his early teens before adopting the posture of apostasy that got him kicked out of Saint Anne’s.

Catholics who renounce the faith and become atheistic live in opposition to what they’ve renounced, which defines them as much as if they hadn’t renounced it. Bob understood that and avoided it. He had instead a much more open-minded kind of skepticism, which you might call agnostic, though I don’t think that’s exactly right. He had a religious sensibility which is always felt in his work, one way or another. For Damascus Gate he got very involved in Kabbalah and was attracted to the idea that Creation was a sort of Big Bang event that scattered tiny sparks of God all over the universe, leaving humanity the task of reassembling them. At the end of his life I think his attitude toward divinity was a sort of hopeful “maybe.”

AV: There is sometimes a question of whether a writer is more productive with a wife and children as opposed to not having them, but Stone’s productivity does not seem fathomable without Janice. You state: “There’s a Janice avatar somewhere in almost every Robert Stone novel.” How important was Janice to Stone, not only as a wife, but one who gave balance to his life and even helped with his editing?

MSB: Hugely. Michael Herr called her “the patron saint of writers’ wives.” It’s not an exaggeration. Janice was muse, assistant, secretary, logistician, travel agent, manager, editor, and continuity person for the later novels. Bob knew how important all those roles were, having asked her to quit her job in social work to assist him full-time. (I got the benefit of many of her skills myself, while working on the biography.) Their marriage was founded on love, with the troubles love is heir to, but also on tremendous respect. The Janice avatar in the fiction is there to straighten the protagonist out, and if the protagonist ignores that, it can be fatal. From a childhood where his only family was his mother, Bob derived the idea of “two against the world.” In adult life the two were he and Janice. The sexual straying is trivial compared to that; their first and strongest loyalty was always to each other.

AV: Do you think Children of Light was a drop in terms of quality from Stone’s first three novels, and if so, can this be attributed to the great amount of alcohol and drugs under whose influence Stone wrote it? Your biography gives incredible insight for the decades-long battle Stone had with drugs and alcohol. By chance, I was looking at my interview with Stone in 1990 (after Children of Light had been published and right after Stone had completed the manuscript for Outerbridge Reach) and I asked him about taking drugs and his response was: “I never became addicted to drugs. I don’t think drugs particularly interfered with my life. Obviously, around the electric scene described in The Electric Kool-Aid Acid Test drugs were taken. I don’t know how different my writing would be without drugs. I certainly don’t write in a state of intoxication of any kind. I do not take drugs or drink in order to write. I don’t write stoned in any way.” This seems to contradict what your biography reveals, and I can only assume Stone was lying to cover up his addiction.

MSB: Doubtless there was an element of classic addict’s denial (and wishful thinking) in what Stone told you. I’m sure he imagined a self that could take it or leave it alone. But also, I heard him say the same sort of thing in other contexts and for a different, more practical reason. He depended on teaching for a stable income and for most his teaching career drug use was classed as “moral turpitude,” for which tenure can be revoked, etc. I saw him get baited about drug use in public; he’d have to deny it, for the reason given.

Meanwhile I think Children of Light stands with the best of his books, although, like many, I was disappointed when I first read it. Aficionados of A Flag for Sunrise wanted another big, world-historical novel about grand sociopolitical struggle, and Children of Light didn’t look like that . . . at first. I was reading it for the sixth time when I thought, hey, there must be something about this book that I like. In the end, it’s very seriously about good and bad faith in the making of art—a topic as important as any Stone tackled. And the protagonist is the most complete self-portrait Stone ever put into fiction: abjectly addicted, yes, but also possessed of a lethal wit and a kind of real brilliance (at least sometimes), whose self-destructive impulse is matched by a capacity for redemption.

AV: There is a quote from Gordon Walker in Children of Light, essentially echoing Stone’s own inner voice, about squandering his vocation: “If I was that good, I would never waste a moment. I’d be at it night and day. I’d never drink or drug myself or be with a woman I didn’t love.” What a great statement and yet how ironic.

MSB: Heartbreaking too, because if Walker’s never really that good, Stone most definitely was. Maybe he just didn’t believe it, or not strongly enough.

AV: What do you make of the critics who compared Stone to Hemingway, Graham Greene (“whom he consistently loathed”), and especially Conrad, whom he often mentions as an influence?

MSB: Conrad is, as you say, an influence that Stone avowed; he frequently quoted Conrad to students. Certain statements Conrad made about the practice of writing were crucially central to Bob, particularly this one:

To snatch in a moment of courage, from the remorseless rush of time, a passing phase of life, is only the beginning of the task. The task approached in tenderness and faith is to hold up unquestioningly and without fear the rescued fragment before all eyes in the light of a sincere mood. It is to show its vibration, its color, its form, and through its movement, its form, and its color, reveal the substance of its truth—disclose its inspiring secret: the stress and passion within the core of each convincing moment. In a single-minded attempt of that kind, if one be deserving and fortunate, one may perchance attain to such clearness of sincerity that at last the presented vision of regret or pity, of terror or mirth, shall awaken in the hearts of the beholders that feeling of unavoidable solidarity; of the solidarity in mysterious origin, in toil, in joy, in hope, in uncertain fate, which binds men to each other and all mankind to the visible world.

Being grouped with Greene under the rubric of “Catholic novelist” irritated the hell out of him, for fairly good reason. Even as Catholics they are dissimilar: Bob a lapsed cradle Catholic, Greene a vigorous convert—a difference strongly expressed in their work. The far-flung settings of their novels are another superficial commonality. Bob detested Greene’s personality, as he understood it; that’s expressed in his preface to a late edition of The Quiet American—though alongside some serious respect for the work.

Comparisons to Hemingway are also superficial—two bearded adventurers with abodes in Key West and a taste for world travel and international narratives. I do think they share a strong interest in the meaning of human suffering. Bob probably thought more deeply about Hemingway than about Greene, given this interesting line in a letter to Sven Birkerts: “I think a lot about Hemingway. His work is the best argument I know for the principle that style represents moral perspective.”

AV: Conrad can be categorized as a writer who writes fiction with a moral purpose, which writers such as Stone and John Gardner subscribed to as well. You mention John Barth in Child of Light on several occasions, whom Gardner castigated in his nonfiction book On Moral Fiction. It appears Stone was not on intimate terms with Barth when they were both teaching at Johns Hopkins. What are your thoughts about their relationship? What is your opinion of Barth, whose early fiction was exceptional, but who is now in his nineties and sadly almost forgotten by the literary community?

MSB: First wave metafictionists, (Barth, Pynchon, Donald Barthelme, et. al.) generally went past me. Reading Barth’s early work felt to me like watching a magic trick without the magic. Not that there’s anything wrong with it. C’est pas mon truc, c’est tout. I never read his long novels either, it would be fair to say, and perhaps unfair to say that the reason was that they bored me. He published a couple of collections of stories while I was teaching at Hopkins and those I thought were wonderful, so go figure.

I didn’t know Barth well when I was teaching at Hopkins, but he was always cordial. He gave good weight (precisely measured) as a teacher. A nice precision was built into him, perhaps. If someone had set out to design two personalities to abrade each other at every point of contact, Stone’s and Barth’s would have filled the bill to perfection. In theory, Stone was hired to replace Barth; they should have overlapped by only one year, but Barth changed his mind, resulting in a new situation in which Stone and Barth would share not only the theoretical throne but also the physical office. Barth had a very ambivalent attitude toward retiring from Hopkins and did it in very slow motion. Stone was caught in the consequences of Barth’s last second thought. Co-existing with Barth ad infinitum was not something he could tolerate. That Stone’s work and Barth’s were completely opposite in motive and intention was also a factor, I’m sure.

John Gardner was a really good novelist who might have been a great one had he lived, but On Moral Fiction is a self-serving work, not to be taken seriously except for the good bits, all cribbed from Tolstoy. In that vein, Stone’s “Reasons for Stories,” published in Harper’s in 1986 as part of a public argument with William Gass (representing the first generation metafictionists) is a lot better, and doesn’t suffer from being a lot shorter.

AV: Will anything ever appear from Stone’s manuscripts of Opus 5/Opus 6/Charlie Manson’s Gold and Arcturus, the latter of which seemed to have great potential?

MSB: Who knows, but I doubt it. Very little was actually written of Arcturus, though somebody might play off Stone’s truly amazing plan for the work (that would be on the order of my long-ago fantasy of writing Dostoevsky’s unwritten novels). Janice and I actually joked about the notion of my finishing Charlie Manson’s Gold, which, at 200+ strong pages, should have been over the hump. Those pages show an aspect of Bob’s personality that he never really put into any other fiction, and there’s a much larger role for the Janice avatar than usual; those are two reasons I wish he had finished it, and also why I don’t think anyone else could.

AV: Bay of Souls is likely Stone’s least effective novel, but Death of the Black-Haired Girl was a good read. One wonders what he could have written without having so many physical issues. You saw him in the later stages of his life and this must have been difficult for you to see. I can only imagine how Janice coped with everything.

MSB: I’ll still say that Bob Stone’s worst novel is better than most people’s best. Bay of Souls has got problems—he almost died during the writing of it, and in some places that shows—but still eminently worth reading. The last scene, in particular, is remarkably strong.

But more importantly, he was determined to come back from that low. There were a handful of books he wanted to write and he was determined to live long enough to write them (he told me that in person, one day we ran into each other in Paris). And he fought to live, not only via the trips to rehab, which improved things for a spell even if they didn’t stick long-term, but also in doing everything possible to fight off his COPD, which is what actually killed him in the end. He didn’t live to finish all the work he wanted to, but Death of the Black-Haired Girl and Fun with Problems do show that the effort was worth it.

AV: Finally, I was wondering who your favorite character is from Stone’s novels, your favorite novel, and how should Stone be remembered?

MSB: I don’t want to play favorites with either characters or novels. But I can say that even minor Stone characters, as Ford Madox Ford recommended, are so real you can smell their breath. If you put yourself in the mind of God, how can you love one more than another?

I think Robert Stone is the writer of his generation who, like the great nineteenth century novelists and those of the early twentieth, pushed the possibilities of realistic fiction—the representation of who we are in the time we live in—as far as they can go.

Click here to purchase Child of Light

at your local independent bookstore

Ntozake Shange

Ntozake Shange