Volume Four: North African Literature

Volume Four: North African Literature

Edited by Pierre Joris and Habib Tengour

multiple translators

University of California Press ($39.95)

by Brooke Horvath

The first two volumes of Poems for the Millenniumanthologized experimental poetries from the fin de siècle to the end of the twentieth century; the third gathered those Romantic and Post-Romantic poets out of whose work the several varieties of modernism emerged. All three volumes made room for writers from around the world but focused primarily on North Americans and Europeans. Volume Four, described by its editors as “a natural progression from its predecessors,” compiles work primarily from the Maghreb (North Africa from Tunisia west to Mauritania) and from al-Andalus (eighth- to fifteenth-century Moorish Iberia). Although their primary interest is poetry, the editors have made room for creation myths, folk tales, legends, riddles, pictographs, parables, and proverbs as well as excerpts from novels and from a great variety of nonfiction—from Ibn Sharaf al-Qayrawani’s eleventh-century “On Some Andalusian Poets” and Maimonides’s Guide for the Perplexed to Tahar Haddad’s 1929 plea for equal rights for women, Frantz Fanon on the “colonized intellectual,” and Malek Alloula on postcards and the colonial gaze.

In myriad ways, historically North Africa has been deeply involved with western thought and culture, and to remind us of how far back this connection goes, editors Pierre Joris and Habib Tengour open with “A Book of Multiple Beginnings”: brief selections from, among others, Hanno the Navigator (sixth century B.C.E.), the Greek poet and scholar Callimachus, early Church Fathers Tertullian and Augustine, Lucius Apuleius (author of The Golden Ass), Magos (whose Punic treatise on agriculture survives only in Greek and Latin fragments), and the sixth-century C.E. Roman poet Luxorius of Carthage. Following are five diwans (meaning a “collection” or “gathering”). The first is devoted primarily to examples of early Andalusian, Sicilian, and Maghrebi lyric poetry. The second, “Al Adab: The Invention of Prose,” samples thirteen prose authors from the eleventh to the sixteenth centuries; the third gathers prose and poetry from the five centuries of “cultural slumber” following the fall of Grenada in 1492 and is followed by “Resistance and the Road to Independence,” which presents work written during the years of colonial rule. A sizable double diwan of postcolonial work subdivided by country brings the collection into the present.

Inserted between the principal diwans are six briefer sections. Three are devoted to oral traditions—transcriptions of often anonymous tales, songs, fables, and folk poetry as well as recent examples drawn from working-class “bards and popular tellers of tales”—while the other three sections highlight topics of special interest: esoteric Sufi poetry (“A Book of Mystics”), examples of Arabic calligraphy (“A Book of Writing”), and “A Book of Exiles,” which spotlights both writers (such as Jacques Derrida and Hubert Haddad) who emigrated from the Maghreb and writers (Paul Bowles, Juan Goytisolo, Cécile Oumhani) who made North Africa their home. Brief introductions preface each section, offering concise remarks on poetics, history, and politics (these are sufficiently up-to-date to consider the up-in-the-air consequences of the Arab Spring). In lieu of headnotes, most selections conclude with a short “commentary” that provides biographical information, comments from other scholars, and information otherwise meant to aid comprehension and appreciation. The editors, however, do no more than nudge readers in helpful directions; nowhere do they insist that we notice and admire what struck them, or understand the texts as they do.

Although repressive regimes have taken their toll of the possibilities for poetry over the past half century, post-independence North African literature is extremely well represented with ninety-six authors anthologized (the majority from Algeria, Tunisia, and Morocco). The premodern poetry assembled, important in its own right and both accessible and charming, serves also as context for the modern work, limning “the historical processes that led to the most innovative contemporary work” from the Maghreb. However, the evolution of Maghrebi poetry is explained rather piecemeal throughout via the abbreviated introductions and commentaries, and a more sustained account would be welcome. Additionally, given that this anthology constitutes the fourth volume in the series described above, more might have been done to chart the cross-fertilization of North African and European literatures (especially given the editors’ emphasis on twentieth-century innovation). The impact of colonialism; the continuing choice of whether to write in French, Spanish, or Arabic; Europe as haven from persecution and locus of publishing opportunities: these facts are clear. Less clear is how the anthologized writers have reworked the literary lessons of European modernism and postmodernism, or what European writers have learned from them. When an infrequent nod is made in this direction, the gesture is telling. For instance, the editors relay scholar Robert Irwin’s suspicion that “Ibn Shuhayd’s fantasy of an afterlife . . . may have indirectly inspired Dante’s famous Divine Comedy,” but how this may have (indirectly) happened is unelaborated. Again, Ezra Pound’s insistence that European lyric poetry began “in the French/Occitan troubadour tradition” remains “canonical” to this day, the editors observe, despite the fact that since 1928 it has been known that “the obvious root oftroubadour is the Arabic tarab,” hence pushing the origins of lyric poetry across the Mediterranean or into al-Andalus, but this information goes nowhere save to provide an example of another “deeply denigrating attitude” toward Arabic achievement and influence.

These are, however, small complaints, and the editors have rightly kept their focus on the literature itself. Perhaps for similar reasons, they have elected not to annotate individual texts, a task that, once begun, would doubtless have left a good third of many pages deep in footnotes. A glossary might alleviate some occasional puzzlement, for it proves difficult to keep in mind terms that, once defined, are subsequently deployed elsewhere; the assumption seems to be that readers will plow straight through these 744 pages (and indeed I did so for this review, but that’s not how anthologies typically get read), and that they all have excellent memories. What, again, does naqd mean? Najd? Muwashshada? Razzia? Also useful would have been a bibliography listing the several books and articles mentioned passim in the commentaries.

I suppose I could keep nickel and diming my betters: why are writers who have published volumes of poems represented instead by excerpts from novels in a book professedly devoted to poetry? Why are five Maghrebi writers singled out for inclusion in the “Book of Exiles” when more than a dozen others located elsewhere in the book also seem to have left North Africa for good? However, the principal point to be made is that this is a magisterial effort by two absolutely serious and accomplished poet-scholars. It is an important addition to the Poems for the Millennium series and significant in its own right, both expanding and complicating notions of the modern by introducing us to many writers we might not otherwise encounter. Moreover, as one turns from the spare poems of Mohamed Sibari to an excerpt from Tahar Ben Jelloun’s early novel Harrouda, or from an ancient Berber tale about the first humans to Omar Berrada’s curious meditation on ’pataphysics and the work of bpNichol, from examples of Shawia amulet inscriptions or an eleventh-century drinking song to Tuareg proverbs or Sheikh Nefzaoui’s fifteenth-century list of “The Names Given to Woman’s Sexual Organs,” the variety and manifold pleasures on offer quickly come clear.

Although female poets were few in the Arabic past, they are well represented in the later diwans, and even in the eleventh century, Wallada bint al-Mustakfi wrote straightforwardly from Córdoba, “By Allah, I’m made for higher goals and I walk with grace and style. / I blow kisses to anyone but reserve my cheeks for my man,” while Hafsa bint al-Hajj Arrakuniyya, a twelfth-century woman writing in Granada, averred, “If I keep you in my eyes until the world blows up I’d still want more.” With equal flirtatiousness, the Shawia bard Aissa al Jarmuni al Harkati (1885–1946) offers this four-line wink:

You are Jews and your black veils are pretty,

and how beautiful is your women’s talk!

My fate is to die with so much pain inside

for I don’t know how I can forget your beauty!

Less amorously, the contemporary Algerian poet Hamid Skif manages to violate at least a couple taboos in “Poem for My Prick”:

Today they are burying my dog of a prick.

The imams surround it,

Those crows at all major feasts

Psalmodize

Its arrival in Paradise.

Just as disenchanted, if for different reasons, is Hamid Tibouchi (b. 1951), who laments while looking out a train window, “my god! so many beggars! / they have replaced the trees / that once lined the sidewalks,” or Mustapha Benfodil (b. 1968), who protests, “I asked the hill for a light / It gave me a tank / Pulverized by a scream.” Similarly, Mohammed Bennis (b. 1948) despairs, “Will I speak to you of people resisting exile and suffering? / Will I speak to you of a village where men women / children were exterminated? . . . What do you want me to tell you?”

Under the influence of modernism, much of the recent poetry gathered here becomes more elliptical, more recognizably innovative, as in this stanza from Amin Khan’s prose poem “Vision of the Return of Khadija to Opium” (first published in 2012):

you are no more the sensitive prisoner rolling in the flight the rust the hair the bleached static of your body captive memory stopped in the silence of midday perfumes the odor of liberty white opacity that expands it’s the death of you that touches me and brushes me with your fingers and pulls me toward your body of sadness neglecting

Or again, these lines from Jean Sénac’s “Heliopolis”:

So each was allowed to perish according to his joys.

The words no longer encumbered the vertebrae

Nor the marrow our horizon.

All hurdles abolished, you followed into the steps of those

who no longer expect the halt.

And they know what is stardust around our blood,

which is the paraphrase of nothingness.

“Raise your voice / with the tongue / of your pen,” wrote the early cabalist Abraham Abulafia more than seven hundred years ago, and this is what these writers have done for millennia, writing in Greek, Latin, Hebrew, classical and vernacular Arabic, French, Spanish, Amazigh. Reading them provides more than the pleasure of seeing “what the poets in North Africa are doing these days.” Although Stephen Watts insists in the Summer 2013 issue of Banipal that this anthology “should not be read as filling a gap in our ignorance, but rather as indicating a source of difference . . . another regime of cultural viability,” I cannot see why erasing a smidgen of our ignorance would be wrong, for as Joris and Tengour calmly observe, this literature arrives from a part of the world “whose cultural achievements—including their impact on and importance for Western culture—have been not only passively neglected but often actively ‘disappeared’ or written out of the record.” Perhaps Watts means to discourage an idle curiosity or premature readiness to deny differences, to see only oneself in these others. Still, given the amount of bad press countries of the Maghreb routinely receive here in America and the number of unfortunate caricatures misinforming the West from foreign-policy assumptions to popular culture, acknowledging difference can be only half of the story. The other half must be the encouragement of empathy and identification. Thirteen years into our new millennium, that would constitute a welcome difference.

Click here to purchase this book at your local independent bookstore

David Jauss

David Jauss

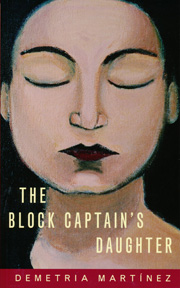

Demetria Martínez

Demetria Martínez Anthony Varallo

Anthony Varallo Eric Lundgren

Eric Lundgren Trans and Genderqueer Poetry and Poetics

Trans and Genderqueer Poetry and Poetics Volume Four: North African Literature

Volume Four: North African Literature Jim Cohn

Jim Cohn Malachi Black

Malachi Black Jen Hofer

Jen Hofer

Alfred Corn

Alfred Corn