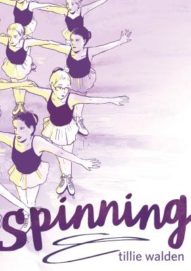

Tillie Walden

Tillie Walden

First Second ($18)

by Stephanie Burt

Spinning presents itself, accurately enough, as a familiar kind of graphic novel, or graphic memoir, or whatever it is the kids these days call book-length comics about the author’s youth (like Alison Bechdel’s Fun Home or David Small’s Stitches) written primarily with adult readers in mind. Tillie Walden organized much of her life, in those years—or else adults organized it for her—around figure skating: her title, her through-line, and most of her subplots reflect all the time she spent at the rink, where she was encouraged, heartened, restrained, guided, saddened, and ultimately rejected by her sport’s perfectionist, team-oriented, and feminine norms.

It’s a beautiful story, a complicated story, and a quietly heartbreaking one, with moments that made me want to throw things; it’s almost the opposite of the conventional sports story in which setbacks lead to triumphs and the big contest comes at the end. Instead, it’s a very careful, mostly melancholy, braided narrative about how to identify false starts, how to find true friends, and how to extricate yourself from institutions and norms that aren’t for you.

That kind of praise makes the book seems all too instructional, or too close to negative stereotypes about YA. But it’s better than that, and more complicated, and slower-moving too. A book that wanted mostly to teach us a lesson (as Walden’s coaches wanted to teach her lessons; as her teammates, too often, did too) would spend less time on purely visual contrasts, on freeze frames, on white space, on an empty rink with skylights, on manga-style depictions of hot pursuit, on how Texas sky looks when you wake up just before dawn. Both the visuals and the terminology that come with figure skating give Walden obvious metaphors: it’s cold all the time; she faces a dauntingly empty expanse, a blank space; she has to spin and flip and jump, as if to escape the path she’s on, though really she’s going to come down near where she began. (When she loses her ability to jump, it’s a big, and very bad, sign.)

Spinning is, in other words, a book that takes consistent advantage of comics as (you’ve heard this one before) a visual medium. The beautiful, understated, slightly uncertain line that Walden developed to tell her own story rejects the deliberate ugliness of other famous graphic memoirs, but it also rejects the kind of highly wrought perfection she would have to embrace had she remained in the sport. Rather than Bechdel, or Small (whose book appears in one panel!), or Lynda Barry, Walden’s spare, friendly, bittersweet visual style, with its blocks of negative space, expressive faces, and sometimes wavy lines, comes closer to Jillian and Mariko Tamaki. As in the Tamakis’ books, the washes and open spaces, the color blocks (here representing skylights and ice rinks), the unfinished lines, leave space for a girl who’s not sure what she wants to become. And yet the young Walden is, in so many ways, already herself: loyal, stubborn, unstylish, needy, craving approval, reluctant to disappoint.

She’s also very queer. Interviews treat her crushes on girls her own age, on older girls and women, and the story of her first girlfriend as a subplot, but these aspects of the young Walden’s identity are, at the least, things no reader can skip: if you’re seeking queer moments (and not everyone is) there are moments when you’re going to cheer for her, and at least one moment that may make you want to break all the glass in the house. In between, there are girls in the dark, sincerely devoted and tenderly serious, checking their phones, trying so hard to get past the fear.

Figure skaters, like gymnasts and classical musicians, are watched and graded for every detail; Walden wanted to skate, but did not especially want to be watched. “The best part” of extra-early practice “was that all the other girls were getting ready. . . . No one could watch me.” That wish to perform, but only when no one is watching, isn’t just a problem for figure skaters, or even for other performers (dancers, gymnasts) whose whole body is at stake. Skating, “a perpetually nerve-racking experience” with its constant series of tests, might also put some readers in mind of the academic tests, the series of multiple-choice gates and gatekeepers, that organize many other kids’ early lives. Skaters, too, take tests: “Testing felt like a prolonged spasm. . . . It was intricate patterns and minute details under the veil of makeup and freezing air.” “I had to prove that I deserved to be here.”

Walden opens with an adult return to the ice rink: “Everything feels just like it used to and I want to run away.” All that blank space in her rinks, her malls, her classrooms, around the bodies of her skaters, solicits not just identification but sympathy: you may see yourself in her, but you may also want to enter the frame, to keep her company, to hold her hand. When she loses her glasses on the ice, you are there in the close-up, low-to-the-ground panel as she tries to pick them up. She does pick them up, but she has trouble seeing what the other girls know they should see: not just rules of deportment, rules of skating competitions, but the apparently random social rules that seem to leave nobody satisfied, not even the alpha girls who enforce them. “You can hang out with the girls on our team, the Sparkling Stars, but, like, the other girls are off limits.”

Tillie badly needs trustworthy adults, first in her coaches and then in the arts, as substitutes for her distant parents; for whatever reason, she gives herself to these adults entirely, starting at a very young age. “I came to her lessons just to be in her arms.” One of these adults takes obvious advantage; most do not—they are just better, or worse, parent-substitutes. She also needs peers; among them, she often feels young and unsure. “The other girls always seemed so much more confident, so much more grown-up,” she remembers in a three-panel page, its middle one dancing torso, its top and bottom two pensive headshots.

Most of us have been told over and over and over that confidence, and the feeling of being grown up, come either from recognized academic success, or else from falling in love in the right way, or perhaps from physical, sexual success. These messages—not to put too fine a point on it—are destructive garbage even if you’re cisgender and straight, and they’re even worse for you if you’re not. Walden’s discomfort with skating (even as she gets better and better at it) starts to look like her discomfort with compulsory heterosexuality: “I quietly fell in love over and over again, never once thinking it could ever be real.”

Another kind of athlete might have lost herself in competition—sublimated, as Freud would put it—in order to get away from all those feelings, and Walden tried hard: “I wanted to chase that high, that thrill of success.” For some athletes (and mathletes and debaters and young violinists and so on) first place is dessert; the whole performance is fun. For the young Walden, on the other hand, only success, first place, could bring a thrill: even second place made the whole thing not worthwhile.

It’s hard even to explain, if you haven’t had them, the mixed feelings that come from this kind of immersion in competition: to make them explicit or clear, using only words, would falsify the feeling that kids have, the feeling many kids never quite admit, that whatever you want for yourself, it’s just not this. That’s a feeling you can have about a sport, or a discipline, or a life course, with its prescribed social and sexual roles. Comics suit Walden so well because their open-ended contrast between words and pictures, their juxtapositions without explanation, let her describe that shapeless dissatisfaction, that sense of the studious self adrift in space. (There’s even a scene—set in darkness, with one cone of light—where she tries and fails to write her feelings down.)

Yet Tillie does have triumphs, and she does benefit from compassionate adults, and above all she finds friends—not false friends but true allies, boon companions, among them Lindsay, the slightly older skater to whom she dedicates the book, and Rae, about whom I don’t want to say too much, except that I wish that Walden would tell us—in an epilogue to the second edition, or via Twitter, or somehow— where Rae is now. When you get to the end of the memoir you’ll wonder too. Have a box of tissues ready. Unlike most sports memoirs in any medium, this book will not make you want to try, or watch, the sport; it’s more likely to get you to pick up the cello. But it will surely make you want to look hard for whatever Walden does next, and—at least if you grew up queer in a highly competitive, disciplined environment—it will certainly make you recommend it to people who might, also, have been there.