Amy Schutzer

Amy Schutzer

Arktoi Books ($16.95)

by Laura Maylene Walter

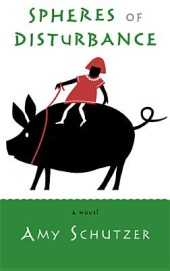

A pregnant pot-bellied pig, a life-sized Elvis cutout, and a garage sale hoedown might share space in Amy Schutzer’s novel Spheres of Disturbance, but quirkiness aside, the novel also grapples with far more solemn subjects: the inevitability of death, the renewal of life, and how characters either confront or avoid mortality.

Spheres of Disturbance is structured in short chapters that alternate points of view. While the cast of characters is large and, at times, a bit unwieldy, the heart of the novel’s action surrounds the poet Avery, her girlfriend Sammy, and Sammy’s dying mother, Helen. As Avery prepares to host a garage sale that morphs into a full-blown neighborhood hoedown, Helen, a terminal cancer patient, makes plans to end her life on her own terms. Sammy, meanwhile, is willfully oblivious of the fact that her mother is dying and does all she can to distract herself from this reality.

The novel’s other myriad plot lines trickle into new territory like so many tributaries: Helen’s estranged family members, who long ago cast her from their home, seek her out in her last days; Avery struggles to maintain her relationship with Sammy while facing tension with an ex-girlfriend; and fifteen-year-old Darla comes of age to discover she, too, might be a lesbian.

That Spheres of Disturbance is consumed with life as much as death can also be observed in the surprising form of Charlotta, Avery’s Vietnamese pot-bellied pig. As the only non-human character granted a point of view in the novel, this pig and her gentle charm nearly steal the show. Charlotta is heavily pregnant and waits for the birth of her piglets with quiet resignation as the party carries on around her:

She drifts, her eyes soft, staring out the door’s window; dusk settles in. The red light bulb is on outside and casts a rosy blush. The snow falls through the light like powdered sugar. The scent of wood smoke swirls with the wind that enters each time the front door is opened and closed. Wind and wood smoke, snow-tinged, brisk, and merry as the river. Curly patterns, lovely smells. Her eyes close as if something—the snow, the wind—has closed them for her, and the pinky light from the bulb outside has taken up residence inside her. What sweetness to roll in crackly red maple leaves and scout the woods for odorous morsels? There is more mud and fungi and the loot of decay, and Charlotta is drooling when the two girls find her napping.

Set in late autumn, the novel skillfully mirrors death through the changing seasons: as the book progresses, the temperature drops and the first snowfall drapes the world in white. These natural details call attention to Schutzer’s luminous prose: “The maple and linden leaves continue to pour down and scurry in circles. The river carries them like streamers. Many rise, like flames, off the water, then settle down for a long drift.” And Helen’s serene moment of viewing the newly fallen snow creates a moment of both peace and surrender: “She looks outside at the snow, and all of a sudden she is in tears, joyful. This is a last bit of good fortune, to witness the grace of snow, as nature surrenders to it, to be buried beneath its beauty without resistance.”

If the novel’s momentum feels a bit stagnant at times, or the ever-rotating point-of-view characters overwhelming, it is the persistence of the novel’s inevitabilities—birth, death, community, life, love, anger, and forgiveness—that come together to create the striking and beautifully ambiguous ending that lays to rest the complexities of the characters’ struggles and pleasures.