By Scott F. Parker

You can’t spend much time in Uptown Minneapolis without hearing the name Dessa. It is sometimes spoken with admiration or reverence, sometimes with fascination or curiosity, but never with jealousy or resentment. Minneapolitans’ pride in Dessa treats her less as a musician than as something otherwordly, celestial. We know her as a star that by some fluke had until recently only been fully observed, by Dessa’s own estimation, “between Franklin and Lake Street.” Even better nationally known Minnesota rappers such as Atmosphere and Brother Ali don’t engender the same genuflection. But Minneapolis positively revels in Dessa—her music, her words, her very existence.

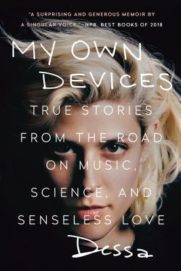

If you’re unfamiliar with Uptown, there’s a decent chance you’re unfamiliar with Dessa too. I was before I moved to Minneapolis. Who is she? I could start with rapper, singer, essayist, poet, businesswoman, but it would be more to the point to put it this way: Dessa is the best kind of artist—the kind people pay attention to.

Prior to the “Literature and Hip Hop” featured event that Rain Taxi hosted at the 2015 AWP conference, I spent time with Dessa’s music and was drawn deeply into it: the dense, imagistic writing, the figurative language, the themes embedded but not explicated in the narratives, the purposeful maturity of the speaker. She might have been overstating the case when she called herself “an underrated writer, overrated rapper,” but she is a writer’s rapper in any case. No throwaway lines, nothing that wouldn’t benefit from textual analysis. But rapping isn’t writing. It’s a performance. After the event, my interest centered on how she creates her rap persona and how that persona relates to the music and to her, and I asked to meet her.

As I geared up for our conversation, I learned more about Dessa and was intrigued by our proximity and common background. We were the same age and had some mutual friends. We both studied philosophy in college and followed that interest to literature, creative nonfiction in particular. She was sending essays to the New Yorker before turning her attention to hip hop; I would have been a rapper before a writer if I had even half a sense of rhythm. She names Dave Eggers and David Foster Wallace among her favorite contemporary writers. In 2009, she published her first book, Spiral Bound (which was not), and I finished a graduate thesis called Stapled Together (which was not, but which was inspired by Eggers and Wallace). But for all we had in common, there was the huge disparity of celebrity between us; it filtered our emails back and forth.

As I geared up for our conversation, I learned more about Dessa and was intrigued by our proximity and common background. We were the same age and had some mutual friends. We both studied philosophy in college and followed that interest to literature, creative nonfiction in particular. She was sending essays to the New Yorker before turning her attention to hip hop; I would have been a rapper before a writer if I had even half a sense of rhythm. She names Dave Eggers and David Foster Wallace among her favorite contemporary writers. In 2009, she published her first book, Spiral Bound (which was not), and I finished a graduate thesis called Stapled Together (which was not, but which was inspired by Eggers and Wallace). But for all we had in common, there was the huge disparity of celebrity between us; it filtered our emails back and forth.

I offered to buy Dessa a coffee or a whiskey, depending where she’d prefer to meet. She suggested a neighborhood restaurant with booths, where we might find a bit of privacy. So on a rainy spring day, with water running down my face, feeling like a Tom Waits song, when the hostess asked me the name of the party I was meeting so she could direct him or her to the booth, what could I say but “Dessa” in the most casual manner available to me?

Not much later, not a drop of water on her, Dessa slid covertly into the booth across from me. Coffee was served (for both of us), cream and sugar were added (for her), and soon we were chatting easily.

The most relevant question to me was who Dessa was and how the woman across from me had created her. The origin story, it turns out, is set in a karaoke bar that held spoken-word competitions. Not wanting to get busted, the underage poet took to writing “Dessa” when she signed up to perform. “It was a habit. A stage name. I had never been a fan of my own name. I always thought about what I’d like to be named instead.”

One needn’t strain very hard here to hear the voice of another Minnesota native who changed his name before taking the stage, saying later, “You're born, you know, the wrong names, wrong parents. I mean, that happens. You call yourself what you want to call yourself. This is the land of the free.”

It took Dessa about a year to start identifying with her adopted name. But the significance of the shift was something short of a full personal reinvention.

“Part of it was aesthetic. I liked the idea that I could pick a name that was aesthetically pleasing to me, that was sonorous. I’d heard the name first in a book by Wally Lamb, and I later found out that it was my last name in Greek, which was sort of convenient when I was talking to reporters. I liked liking the word of my name. There was a lot of agency in that. Some Native traditions do that, you get to name yourself. I think that’s great. Of all the things to give someone else the power to do, naming yourself seems like such a great opportunity to exercise your own preferences.”

While many rappers take self-naming to the extreme of full-blown alter-ego creation, for Dessa, it’s something else: “I wanted as little daylight between the person and the persona as possible.”

The best way to characterize Dessa’s rap persona is that she embodies not a story so much as a storyteller. What’s common to her raps is not necessarily that the songs cohere into a larger narrative but that they partake of a singular, and distinctly literary, way of being that is less concerned with what it’s about than it is with how it’s about it. Like all rappers, Dessa’s flow is her essence. But more than most, within her flow, style takes precedence over content. Is it any wonder that she thinks of herself as an essayist?

Dessa discovered the personal essay as an undergrad at the University of Minnesota. “I didn’t really know what creative nonfiction was, but I read about it in the course guide and thought it sounded like a good creative writing class. The instructor was Thomas Haley, and I was just head over heels for the course content, for the dude himself. I was just all fucking in. I didn’t know you could do any of that, I didn’t know it counted, I thought if you wanted to be a writer that meant you had to write something that was 300 pages and it was one story and it had a plot. So to find these guys—Sedaris particularly was just an easy entry point. Like, he has a business card that says writer on it? That’s amazing to me.”

And as for writers not named David: “Annie Dillard was big for me. Phillip Lopate—I didn’t like his essays wholesale, but I liked some of his turns of phrase. Generally I like shorter stuff. Who wrote The Kiss? Kathryn Harrison. I decided that’s not what I liked. I felt like drawing a line between what I understood to be confessionalism or exhibitionism and stark, frank, risky honesty. Those were important distinctions to me as I moved forward. Intimacy for intimacy’s sake wasn’t something that interested me.”

You see this in Dessa’s raps. Even when they appear to be autobiographical, they’re never confessional and sometimes they’re not even personal. The subject of the stories could be anyone. The “I” could be you. It’s less true of her essays themselves. Spiral Bound brings the reader much closer to knowing the author than her raps do the rapper. But even so, the narrator leads the reader to consciousness, mortality, fleeting moments, and the existential “thud of a feather,” not back to the narrator herself.

“There’s almost no part of my life that isn’t fair game to include in my public life, but the value in doing so isn’t just for sharing’s sake, which I think sometimes gets a little blurred. People get excited by words like brave and intimate and confessional and conflate the artistic merit that can sometimes accompany sharing a secret with the act of sharing the secret itself.”

A my-story-in-rap kind of memoir would therefore seem to go against Dessa’s artistic instincts.

“I’ve been asked to do that. I tried on our last tour. I don’t know why I can’t put those two worlds together. Part of the reason, maybe, I end up doing a lot of my creative writing either about my dad or about travel is because I’ve got the green light to be totally frank there in a way that to make the true stories interesting I’d really have to have license from all the guys in my rap crew to tell—I mean it’s not fun if you just write the good parts. And I feel I don’t have that license to air out other people’s lives. But when I’m travelling with strangers, that’s okay. And my dad’s tough.”

Privacy is huge for Dessa, and as an artist she respects it for others as much as she protects it for herself.

“I can’t talk about the details of my mother’s life or my father’s life or my little brother’s life or my romantic partners on stage without feeling like I’m trespassing their privacy.”

Many rappers, musicians, and artists dodge this concern by invoking persona or a fictional veil. But the thin divide in Dessa’s work between the author and the speaker prevents her this conceit.

“It’s one thing to say I built a mask for myself and that’s what I wear when I go onstage. It’s another thing to say that I built a mask for you that’s completely, obviously identifiable as you. I don’t think there’s any meaningful claim of anonymity or protection there. If Eminem adopts a persona and a character, I don’t think there is an argument of ‘I made a character and a persona that protects you.’ He’s using their real names, he’s trampling on their privacy. I don’t think there is even a strawman argument of protection there.”

Eminem came up in our conversation here because I had once invited Dessa to contribute the foreword to an academic book on Eminem I edited. She declined, and it seemed to me now that this might have been because his approach to rap is almost entirely foreign to hers. He, as much as anyone, employs persona to dramatize some of the ironies of the genre. His escape hatch from responsibility for his most vile lyrics has always been the inherent gaps between real life and art, writer and rapper, performer and performance. You can always defend Eminem by pointing out that text, image, performance are always mediations of so-called “reality.”

“That’s a very inside-the-craft way of thinking about it. If I’m dating a writer and he gives me a caricature of me, and everybody knows we’re dating, and he says this character had an abortion, my question isn’t ‘What about that characterization?’ It’s ‘Dude, everybody knows I had an abortion. You’re a total jerk, Derrick!’ For the person who’s not in the art, it’s not an artistic question, it’s ‘Did you tell my secrets?’ It’s only an artistic question for the dude at the center of the storm who calls himself an artist.”

“That’s a very inside-the-craft way of thinking about it. If I’m dating a writer and he gives me a caricature of me, and everybody knows we’re dating, and he says this character had an abortion, my question isn’t ‘What about that characterization?’ It’s ‘Dude, everybody knows I had an abortion. You’re a total jerk, Derrick!’ For the person who’s not in the art, it’s not an artistic question, it’s ‘Did you tell my secrets?’ It’s only an artistic question for the dude at the center of the storm who calls himself an artist.”

Unlike Eminem’s friends and family, Dessa’s needn’t fear Czeslaw Milosz’s warning that “When a writer is born into a family, the family is finished.”

For a long time one of the pressing concerns in rap had to do with authenticity and the rappers claims to their material. Did the life lived sufficiently match the life rapped? That concern has dissipated as hip hop has become a global culture and increased its diversity of styles and subject matter. By not presenting a character that is any smaller than her essayistic concerns, Dessa skirts the issue altogether. Her songs can come from almost anywhere.

“With some small exceptions. I’d written something that sounded kind of country-western, and I was just like, ‘That would be a tough sell.’ But it’s not because I’m poking a hole in a carefully constructed persona, it was more, ‘Would an audience follow me?’ I did think, ‘How would that look?’ So there’s some of that consideration. But I hope to build something that’s big enough that all my ideas can fit inside it.”

I wonder what that thing is she’s building. Emerson said, “Great geniuses have the shortest biographies. Their cousins can tell you nothing about them. They lived in their writings, and so their home and street life was trivial and commonplace.” Perhaps Dessa is so private because she knows that her legacy is the work she leaves behind. And that work needn’t be a vehicle for conveying the identifiable biography of the author. And yet:

“Because I do have such a strong attachment to creative nonfiction, artistically I’m really, really compelled by truth. So by whatever alchemy you use to turn real truth, real lived life, into art on the other side—I think most of the lyrics in my songs are literally true. If there’s a talking crow, that didn’t happen. But a song like ‘Call Off Your Ghost.’ I went to a wedding. There’s my ex-boyfriend. He’s got a suit on. I didn’t even know he owned a suit. That’s a literally lived experience, and then trying to figure out, in this bloom of feelings—Where is the artistic turn of phrase? What’s the best person I can be for this scenario? How do I capture that impulse in a way that bears being sung four, five times in a row?”

This question of becoming the best person for the sake of reaching certain ends is the kind of thing I’m trying to home in on.

“In my offstage life there are some moments when I feel more me and less me. Sometimes I’ll finish a conversation on the phone or whatever and think, ‘Why do I use such a bullshit phone voice? Why can’t I just talk normally to the person at American Express? Why do I talk like I’m trying to impress her, like, “Well, hello, ma’am.”?’ And I’ll think, ‘Where did you learn that particular behavioral convention and why are you conforming to it?’ And then there’s some conversations where I was totally comfortable and I said what I thought even though I wasn’t sure I’d be agreed with. Way to go, true self. And some stage shows I feel very much me, and some stage shows I feel disappointed in me because I didn’t find a way to be the most genuine authentic person I could.”

I have found it impossible to make a meaningful distinction between authentic and inauthentic selves when all selves are performed. But experientially, there are some performances that feel effortless. The self-consciousness of the performance drops away, and we assume—rightly or wrongly—that what remains is true. However, a performer doesn’t reveal her true self. Rather, she gives the impression of revealing it. The self-consciousness is built into the act.

“Onstage and offstage I am keenly aware of what I believe people think of me.” Gesturing with head and eyes over her shoulder, Dessa indicated a man passing our table. “This guy, I think I know what he’s made of. I know what the waiter thinks, the first one and the second one. The first waiter hates my new haircut and said as much. The second one doesn’t know who I am. The table across has been kind of listening to us. I think I know what you think. You maybe think you know what I think.”

It was true about the table across from us. I had a better angle on them than Dessa did, and I could see that they were trying to eavesdrop. Later they would try to capture Dessa in the background of their selfies. But was she right about me? Did I think I knew what she thought? She was basically forcing me to try. Here goes: I think she thought I thought I could somehow see through her in a way that most of her listeners could not. That I thought at the heart of all performance is a kind of inherent fraudulence. That I knew how vulnerable she was. What I really thought was, where does she get such strength from, such composure? If we do have so much in common, how are we still so different? If she is faking it to try to make a certain impression on me, how can I learn to fake it like that?

At the restaurant I didn’t have much time to process her challenge. She was still explaining: “And I’m aware of that onstage. I’m monitoring how many people are texting, how many people are flirting and buying drinks, how many people are yawning, how many people have their hands in their pockets, how many have their hands in the air. I’m very aware of that. And so sometimes I think being your real self onstage or off asks you to suppress the natural inclination to be liked. Because if it’s not suppressed I find myself catering to what I understand as the preferences of a conversational partner or room full of people.”

I asked if being liked felt uncommonly important to her.

“Yeah, much more than I wish it were. I don’t think it’s like eight times as much as most people, but I think it’s more.”

This isn’t what you would ever think being around Dessa. She comes across, more than anything else, as cool. She’s charismatic, and when her attention shines on you you feel charmed. When it doesn’t, you feel like you don’t deserve it. It doesn’t occur to you that such a person stands to benefit from or be hurt by your opinion. Dessa was reminding me of the simple fact that the way a person comes across is not necessarily the way that person experiences herself.

“I think it comes from dads. I read that once and it resonated. If you were involved in a scenario at home where it feels like you are pining for or competing for attention or affection, then you get pretty good at reading the adult world to figure out what earns a gold star or a pat on the head. My dad is one of my heroes, but it was sort of tricky navigating childhood with that dad. And I think I did end up vying for attention and affection, and so you end up being very well tuned-in to small cues about what people like and what they don’t or when your voice is too loud or when you’re playing and you’re annoying someone, the volume of your voice or the bouncing ball. And when you do the little dance the living room likes and I ask you to do it again the next time company comes over. You become very tuned in to how your behavior is received by the larger adult community. And you carry that into adulthood.”

It sounds exhausting to constantly be making such assessments, but then my tendency is to ignore people to prove that I don’t need their approval. How does any person compare the experience of being who she is with one of being who she’s not?

“I don’t know. I’ve never done it any other way. Maybe I’m sapping a lot of energy. But if you’re lucky enough to be in one of those rooms where everybody is really with you, then it can feel all the more powerful. The most successful moments feel like those in which I’m not working hard to perform a feeling but those in which I’m in the throes of a feeling and I just trust it to express itself. If I’m singing a sad song and I feel sad, perfect, people can read that on me, and I don’t have to worry about how to best express it. And if I feel aggressive in a song that’s talking shit, great!”

I’m tempted here—and possibly invited—to think of Dessa as the kind of artist who is only truly herself when she’s performing. That possibility supports the Emersonian sense of a person being the sum of her work, and it makes for good performance. But for the subject herself, does the work ever add up to a portrait of the artist? Does it feel like it to her?

“I think I would be not the last but maybe the second to last to know because in this case I’m so familiar with the subject. I have to maneuver her body around the world. It’s the one I live in. It’s sometimes difficult to compare what you know of yourself to the clues that you have given other people about yourself and to be reminded of the space between those two things. I think I’m probably distracted by my lifelong knowledge of me.”

“I think I would be not the last but maybe the second to last to know because in this case I’m so familiar with the subject. I have to maneuver her body around the world. It’s the one I live in. It’s sometimes difficult to compare what you know of yourself to the clues that you have given other people about yourself and to be reminded of the space between those two things. I think I’m probably distracted by my lifelong knowledge of me.”

Art is often the vehicle of empathy. It can give you access to the world from someone else’s point of view. But the view is always incomplete. The song, the essay, the conversation comes to an end. We return, ultimately, to our own selves, piecemeal as they are.

Talking with Dessa I hear what I hear in her work: a philosopher ruminating on the tension between the inner and outer worlds. This concern is itself indicative of a particular kind of inner life that is not common to all.

“I think that the methodology of philosophy informs my thinking, and of course my thinking informs my writing. Skepticism and charitability both are part of my worldview. They’re the lens through which I do everything, including my art. Skepticism: hearing somebody say something and thinking to myself, Where’d you learn that? Who told you that? Why do you think that? Really pushing at precepts to see if they hold water. And then charitability. As an undergrad, I loved feeling like I could find the logical errors in an argument. That was such a thrill, and I looked for them very hard in old white guys’ stuff. One day my advisor, Valerie Tiberius, called me into her office and said she thought I had some skill but to be charitable in the way I understood the arguments I was trying to deconstruct, particularly because the people who made them were dead. So it was my job to defend their arguments against mine.”

My own philosophy advisor, John Lysaker, used to say “engage your interlocutors” in your writing. Give them the best response to your response and so on. How would they counter your position?

“Not only that, but is there something good here? Yes, there is a potential logical problem on page five, but is there something philosophically valid here too? Are you so high on the thrill of winning that you’re not looking for the best outcome?”

I like that, “the best outcome.” We’re not looking for something that is without flaws but for something that might be useful. A synthesis of widely drawn material that coheres for us for the project at hand. What is philosophy, what is art, but each of us attempting to figure out how to live?