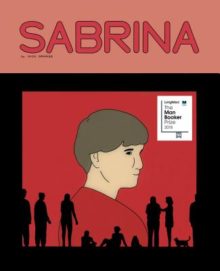

Nick Drnaso

Nick Drnaso

Drawn & Quarterly ($27.95)

by Steve Matuszak

From time to time, the deep-seated feeling that nothing is really as it seems grabs hold of us, the world as we know it threatened with erasure as we buckle beneath the weight of our doubts. Sometimes the feeling is triggered by events outside of us; sometimes it appears to have no cause. The problem is not with reality, of course, but with our understanding of it, the explanations and narratives we tell ourselves to stave off the nagging suspicion that we really don’t know what we’re talking about.

Nick Drnaso’s gripping graphic novel Sabrina drops his main characters right in the middle of this epistemological seizure. The book opens with an innocuous scene of Sabrina and her sister Sandra having a relaxed conversation at their parents’ house—Sabrina is cat sitting—working on a crossword puzzle and planning a bike trip around the Great Lakes in the fall. It ends with Sandra leaving to attend a surprise party, and Sabrina heading out the next morning into what appears to be a brilliant summer morning.

While on the surface the scene may seem dramatically static, there is something off-kilter about it, danger lurking just out of sight. For example, its first few pages depict Sabrina searching for something that caught her attention as she stands at the kitchen sink, facing out at the dark night. Peering into unlit rooms, behind the shower curtain, into a closet, and under a bed, she appears to be searching for an intruder—but in a riff on a common horror film trope, it turns out to be the cat. Immediately afterward, Sandra arrives, startling Sabrina; we also see that one of the crossword puzzle answers is “Dick and Perry,” the killers in Truman Capote’s In Cold Blood. Most unsettling, though, is Sandra’s response to Sabrina’s fear that they might not be safe on their bike ride because of animals; she relates a moment when she was nineteen, on spring break, and was stalked by three men who told her they were “hunting,” one even grabbing her arm before her escape, leading her to conclude, “Don’t worry about riding a bike through the woods. The fucking wild animals stay in hotels.”

Considering that the rest of the book unfolds after Sabrina has vanished, the family’s worst fears eventually confirmed, Drnaso might be laying it on a bit thick here. But for the most part, the drama in Sabrina is understated, rendered in muted colors across comics panels laid out in relatively uniform grids that rarely change much from panel to panel, suggesting the passing of time, minute by minute, in all of its agony, the characters’ dialogue unadorned. The story itself focuses not so much on the crime as on its emotional and psychological impact on two groups of people: Sabrina’s sister Sandra and Sandra’s friend Anna, and, making up most of the book, Sabrina’s boyfriend Ted King (an emotional zombie since Sabrina’s disappearance) and his childhood friend Calvin Wrobel.

At first, reality is cut asunder for these characters by the sheer unreality of what has happened. Both Ted and Sandra become speechless in their grief, as when Sandra, curled in a fetal position in the middle of her apartment, laments, “Sorry, I can’t sit here. I don’t know what to do. . . . I’m serious. I don’t know what to do! . . . God. I don’t know what to do.” After Anna tries to calm Sandra down with a guided meditation, Sandra only ends up shouting, “Ahh!” echoing Ted’s screams from within a nightmare earlier (and again, one presumes, later) in the book.

The events are too unreal even for Calvin, an Airman working a desk job at an Air Force base in Colorado Springs; he tries to comfort Ted but has difficulties expressing all but a kind of surface niceness, and its insufficiency in dealing with these jagged circumstances is exposed again and again: in his relationship with Ted and the abyss that opens up for him as a result of it, and in his strained marriage, his wife chatting with him in brief, shallow conversations via webcam (they are separated, with divorce impending). This kind of thing doesn’t happen to people, at least to people we know. At best, they are horror stories we encounter in the news, perhaps on the Internet as we are checking our emails or social media.

It is in the media landscape, where we go for information, entertainment, and interpersonal connection, that Sabrina locates its most haunting insights. After all, we commonly rely on mass media for answers. Unless we know the people involved, it is where we would hear about something like Sabrina’s murder in the first place, and it is also where we would go to understand it, regularly checking news outlets in multiple platforms for the latest developments, for a deeper understanding of the event and those involved in it, and even for how to make sense of it—what does this event mean, how does it impact my world? So it’s only natural that Calvin goes online to help him figure out what is going on, while unbeknownst to Calvin, Ted turns to the rantings of Albert Douglas, an Alex Jones-like radio host, who sows paranoia in the name of exposing what he calls “the paranoia campaign.”

While Calvin and Ted turn to mass media for narratives and explanations to help them understand their lives, they are also reminded that it is a strange place—located here, where they access it, and also not here, from somewhere in the ether (or, to be more contemporary, the cloud). Its roiling discourse moves in like strange weather—sudden, anonymous, sometimes violent, and always impersonal in the way it uproots what is quite personal to them. But because the media forms this virtual, living web seemingly connecting them with others, it can be hard for them to see how it also isolates them; it might in fact depend on the assumption that they are already isolated from others in order to connect them.

Drnaso vividly captures the sense of isolation that can be experienced in this seemingly crowded media culture in the way he frames each panel. Rarely are there more than two figures in any given panel; often there is just one, each individual isolated from others even when they’re in the same room. Rooms are often empty, even relatively public spaces like the greasy spoon Calvin patronizes that no longer draws the crowds it once did. In fact, we quickly realize the only masses of people to appear in Sabrina, in a large panel teeming with colorful people, is actually a page from Where’s Waldo?, Drnaso using comics to achieve a disorientation not possible in cinema, for example, where a room full of people and an illustration from a children’s book are immediately distinguishable. In Sabrina, however, while there is a shift toward a brighter color palette and a cartoonier representational style, it takes at least a beat to realize what one is seeing: a perfect metaphor for our need to find what we feel we are missing or have lost, and for the sinking feeling that such a need is merely child’s play.

That things are more ambiguous than we would like is emphasized in Drnaso’s drawing style, in which people can sometimes be a bit indistinguishable from one another—we’re not always sure who we’re looking at. Is that a foe or a friend? It’s a question that Ted and Calvin wrestle with in key scenes late in the book, and in simply asking the question, they realize that even should it prove to be a friend, they still can’t be too sure. Friend or stranger, could he be the face behind those trolling comments or that frightening email? In moments of deep uncertainty, we realize we’re never really sure of the things we take for granted, but we never give them a moment’s doubt until something shakes us out of our certainty. Sabrina helps us to see that uncertainty is a condition of life, whether we look directly at it or not. Its final, brief scene reassures us that no matter how alarming or frightening things might appear, it is OK.