ROCKDRILL 8: VIA

Caroline Bergvall

Optic Nerve/Carcanet (£14.95)

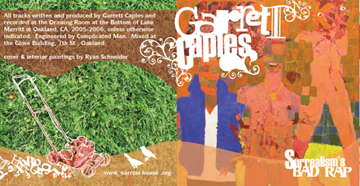

SURREALISM'S BAD RAP

Garrett Caples

Narrow House Recordings ($12)

by Christine Hume

"Here is the great secret:" Tristan Tzara famously manifestoed, "Thought is made in the mouth"—and, I would add, comprehension hits consciousness more directly via listening, which is more continuous with thinking and feeling than reading. Two recent poetry CDs attest to the potency of the mouth as a site where sense and sensuality fuse and refuse to compete. In the mouths of Caroline Bergvall and Garrett Caples, voice pulls our attention toward itself as idiosyncratic sound as it gathers into provocative moods of communication.

Both Bergvall and Caples deliver voices that are deeply marked, accented, tuned to the relativity of meaning and expression. Yet for all their investment in context—situational and temporal specificity—their voices seem utterly unlocatable in very distinct ways. Both voices hold us captive by their uncanniness—in conflict and in contact with a present moment—and their capacities to mutate for each track, allowing language to decompose and reconstitute itself so that its phonemic, morphemic, and paragrammatic qualities air themselves viscerally. Bergvall is especially skilled at using interrupted, partially audible, phantom, and crypt words that percolate in an erotic aporia. Caples sometimes blurts or blurs language, sometimes buries it underneath a guitar as a libidinal articulation of displacement. The corporeal body, its mythological transformations and vulnerability, asserts itself in both voice and language. Body parts come at us in both CDs—sometimes in French, sometimes with diapers, often associated with animals. Both Bergvall and Caples play in the physicality of sound, as lexical inflections of an identity crisis. They rattle and unravel any sense of objective status of gender, nationality, or class. Yet the strategies and effects of their approaches to sound poetry couldn't be more contrary. Bergvall's austere and expertly engineered recordings create an addictive ritual out of her voice, which hypnotizes with braids of polyglot unconscious, whereas Caples' raw, lo-fi brio concocts a series of acoustic adventures, complete with a cadre of collaborators and dedications.

The first tracks of each album buoy up the radically different spirit and aesthetic of Bergvall and Caples. Bergvall begins Via by performing the sentence "Ambient fish fuck flowers bloom in your mouth will choke your troubles away" with the attentiveness of a spell. The words are spoken as if they are irritants on the tongue; they are unruly words simmering with insinuations. The initiating sentence permutates ten or so times, slipping sounds sonically through reincarnations—flowers become fodder, loose, goose, bouche, toche, touch—that land in a psychic stutter opening "a door, adore" on the poem's final perversion. Each sentence, each pronunciation tries itself out, it searches as it drives the saying out of the parking lot of the said. Bergvall's slow start amps up the tension by sharply articulated consonants and prolonged vowels that enact the sense of language blooming in the mouth, choking us, like an irrepressible sob. The passage's subtle, minute shifts in tone conjure sounds between languages and between semantics and music. Rhythm is foregrounded as a medium of somatic communication. Its phonetic rhythm sounds somewhere between lullaby and fucked-up love song. In less that two minutes we get a strobe-light of bloom and choke, of affirmations and negations, of ambivalence and annoyance—of elided sentence and list. The erotics of the language merges with a violent grammar to produce something brutal, obscene, and deeply affective.

Caples's opener, "For Tune," is a chant of coupleted four-letter words, beginning with "Fuck love." Like Bergvall's "Ambient Fish," this piece plays as both list and sentence, alternating between the two in a manner that manages never fully to commit itself to either. This use of ambiguous syntax creates tension and meaning, while it keeps our listening active and amused, keeps us sharp to the interpretive branchings of each word pair. Its word traffic is as much afterthoughts and emendations, precursors and predictors, as it is a narrative. In this way, and due to the intricacies of rhyme, the percussive one-syllable strikes, and the exploration of tensions between "fuck" and "love," the piece feels like an homage to early rap. This poem is bracketed by a tiny introduction of the standard of poetry readings that claims the poem's "unfinished" condition and a long applause that sounds inappropriately polite. If the familiarity of the introduction signals what follows will be a "typical" poetry reading, it only serves to mislead. It does however set the reader up for audible breaths and mouth noises, occasional stumbles or hesitations, dynamic glitches, scrappy recordings, and a "live" intimacy that characterize the entire CD.

Two other versions of "Ambient Fish"—on PennSound, a flash version on EPC—testify to the on-goingness of Bergvall's work, often context-specific, always open to language as an object of desire, sought out and subject to the transformative power of failure and attempt. Many of these pieces are products of much performed and textual revision, and all but one are published in books, sometimes in the spirit of documentation. Though, as in Caples's work, the performance is both tribute to and transgression from textual versions, showing improvisation as an aesthetic and as compositional technique. In fact, one of the most acute differences between the two CDs is that Bergvall's work has clearly always had performance in mind, whereas Caples embraces textual primacy—he renovates the poetry reading, kicks the conventional off stage, without approaching the realm of performance art.

Caples offers us a generous 26 tracks, between 44 seconds and seven minutes, that pack a kinesthetic, gleeful carnival of digital tricks, including at least one veritable song. The strepitant spirit of the CD accretes a riveting intensity studded with gems of sardonic wit. The comic here calls out our complicity in power structures, displaying the unacceptable in a ludic timeliness. What this highwire act of mixed comedy and edgy seriousness foregrounds is the complex balance between performance, which recognizes the audience as "other," and individual artistic gesture, which lives in an altogether other-world. Most of the pieces make more of a gesture toward narrative than "For Tune," but they do so by employing enigmatic phrasing and an almost three-dimensional aural coherence.

With the exception of "Ambient Fish," Bergvall's eight tracks are more expansive, conceptually-driven projects. The splintered and ringing "About Face" anatomizes an art historical perspective on the face as it defaces words to accommodate traces, seams, and fractals of other language events. This track, like most of the CD, trades on using repetition as a temporal structure of the aural imagination (in the same way that an image is a spatial structure of the visual imagination). The titular piece, "Via," sets 47 alphabetically arranged English translations of the first canto of Dante's Inferno noting translator and date; under it—or rather inside it like auscultation—runs a faint musical cannibalization of Bergvall's voice. The succession of effects is always ballasted by the context-alerts of names and dates, never allowing us sensual immersion into its minutely shifting linguistic densities, and thus producing in us a full longing concentrated by the fact that we are not lost on a path in the dark wood, we are passing inscriptions of those who once were.

Perched on opposite ends of an aesthetic see-saw, these two CDs promise us a plurality in audio poetry culture. Anyone who doesn't love them must have a low opinion of joy, that is, thought made and mused in the mouth.

Rain Taxi Online Edition, Spring 2007 | © Rain Taxi, Inc. 2007