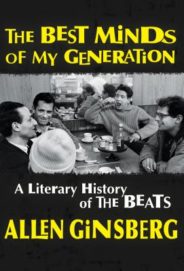

The Best Minds of My Generation:

A Literary History of the Beats

Allen Ginsberg

Edited by Bill Morgan

With a foreword by Anne Waldman

Grove Press ($27)

First Thought: Conversations with Allen Ginsberg

Edited by Michael Schumacher

University of Minnesota Press ($19.95)

by Patrick James Dunagan

Allen Ginsberg’s impact upon the literary as well as cultural climate of the United States during the tumultuous latter half of the twentieth century cannot be overstated. No other American poet has ever achieved the status of countercultural hero that Ginsberg enjoyed, fulfilling Walt Whitman’s declaration in his Introduction to Leaves of Grass to be “master after [his] own kind, making . . . the poems of freedom, and the exposé of personality—singing in high tones democracy and the New World of it through These States.” Ginsberg was a proudly practicing Buddhist homosexual Jewish poet who forthrightly spoke his mind to anyone who cared to listen. Although famous for frank, at times explicit, chronicling of his sex life and drug use, such instances within his writing are in actuality the byproduct of his lifelong discipline to a poetic practice in which observation and detailed notation remain paramount. Far more than chasing hyperbole-fueled scandal or doggedly following the path of raging revolutionary, he was ever the doting Jewish grandmother, always committed first and foremost to being a poet.

Allen Ginsberg’s impact upon the literary as well as cultural climate of the United States during the tumultuous latter half of the twentieth century cannot be overstated. No other American poet has ever achieved the status of countercultural hero that Ginsberg enjoyed, fulfilling Walt Whitman’s declaration in his Introduction to Leaves of Grass to be “master after [his] own kind, making . . . the poems of freedom, and the exposé of personality—singing in high tones democracy and the New World of it through These States.” Ginsberg was a proudly practicing Buddhist homosexual Jewish poet who forthrightly spoke his mind to anyone who cared to listen. Although famous for frank, at times explicit, chronicling of his sex life and drug use, such instances within his writing are in actuality the byproduct of his lifelong discipline to a poetic practice in which observation and detailed notation remain paramount. Far more than chasing hyperbole-fueled scandal or doggedly following the path of raging revolutionary, he was ever the doting Jewish grandmother, always committed first and foremost to being a poet.

In 1956 Ginsberg’s book Howl and Other Poems shuttled him into the national spotlight and he never looked back; he didn’t need to, since he never left any part of his life behind, and he always brought his friends along for the ride. For several years leading up to the publication of Howl, he had been championing the work of his novelist friends Jack Kerouac and William Burroughs, and he continued thereafter for the rest of his life to make sure they would not be forgotten. Almost overnight what had previously been an unorganized, underground milieu of renegade writers, artists, and sometime drug users who hung out at coffee houses and jazz joints from New York City to San Francisco became categorized as the Beat Generation, a label that has never been shaken off. Not that the marketing-minded Ginsberg ever bothered attempting to dispense with having himself and his pals so labeled—he took advantage of having the Beat Generation as a recognizable brand name to push for publication of all their works.

Ginsberg is well deserving of a multi-volume Collected Works. Aside from his poetry and the gargantuan amount of correspondence and other material which has been published, plenty more remains scattered in fugitive publications and sitting in archival sites awaiting dissemination. While such a massive Collected Works is unlikely to appear anytime soon, The Best Minds of My Generation: A Literary History of the Beats, an amalgamation comprising lectures on Beat writing delivered by Ginsberg throughout his teaching career at Naropa and Brooklyn College, along with First Thought: Conversations with Allen Ginsberg, accomplish a bit of the job of further rounding out what is currently available of Ginsberg’s oeuvre. Each book offers unfiltered access to Ginsberg’s always enthusiastic support for his closest friends, namely Kerouac and Burroughs along with poet Gregory Corso, and insight into those matters which Ginsberg believed had the most powerful impact upon all their work, from the vital African American cultural influence of jazz to ecstatic late night conversations high on stimulants as much as each other’s company.

All the interviews in First Thought are previously uncollected. The collection is genuinely worthwhile in its own right; rather than merely reiterating similar information there’s both a cohesiveness here and an easy accessibility that the bulkier Spontaneous Mind: Selected Interviews 1958-1996 (2002) lacks. There are also true rarities, such as Michael Reck’s 1968 “A Conversation between Ezra Pound and Allen Ginsberg.” This recounts Ginsberg’s visit to the reticent master poet shrouded within his self-imposed silence, which Ginsberg infamously managed to pull him out of long enough to receive Pound’s self-condemnation of his spouting “that stupid, suburban prejudice of ant-Semitism.” There is also an amusing joint-interview by Stephen M.H. Braitman between Ginsberg and his father Louis, an accomplished poet given to quaint rhyming verse. The father-son exchange is full of jollity. There is Louis taking delight in his dated, off-color, sexist one-liners (“Poets are born, not paid. But a lady poet can be made.”), as the two poets verbally spar off and talk over one another, leaving a desperate Allen repeatedly pleading with his father, “I want to answer his question.”

All the interviews in First Thought are previously uncollected. The collection is genuinely worthwhile in its own right; rather than merely reiterating similar information there’s both a cohesiveness here and an easy accessibility that the bulkier Spontaneous Mind: Selected Interviews 1958-1996 (2002) lacks. There are also true rarities, such as Michael Reck’s 1968 “A Conversation between Ezra Pound and Allen Ginsberg.” This recounts Ginsberg’s visit to the reticent master poet shrouded within his self-imposed silence, which Ginsberg infamously managed to pull him out of long enough to receive Pound’s self-condemnation of his spouting “that stupid, suburban prejudice of ant-Semitism.” There is also an amusing joint-interview by Stephen M.H. Braitman between Ginsberg and his father Louis, an accomplished poet given to quaint rhyming verse. The father-son exchange is full of jollity. There is Louis taking delight in his dated, off-color, sexist one-liners (“Poets are born, not paid. But a lady poet can be made.”), as the two poets verbally spar off and talk over one another, leaving a desperate Allen repeatedly pleading with his father, “I want to answer his question.”

The “lectures” presented in The Best Minds of My Generation have been chiseled by editor and official Ginsberg Estate archivist Bill Morgan from nearly 2,000 pages of transcriptions he made from the original tape recordings of Ginsberg’s classroom sessions. It is a phenomenal undertaking even to attempt such a feat, let alone pull off the production of a highly readable text, but Morgan has succeeded. And while there is understandably some repetition of certain factual circumstances, along with a great deal of information that has long since been covered in much detail by others, there is still an undeniably charming aspect to having Ginsberg’s perspective as he presented it in real life. Morgan wisely includes the full text of most of the excerpts and in some cases entire poems that Ginsberg reads and comments upon; this is particularly helpful for any readers unacquainted with the full range of the voluminous prose by Burroughs and/or Kerouac.

Morgan also provides some scholarly apparatus, including footnotes which offer up a pair of clarifications regarding factual errors made by Ginsberg when he accepted Gregory Corso’s poetic assertions in the poem “How Happy I Used to Be” to be historically accurate. Ginsberg extrapolates upon Corso’s line “Alexander Hamilton lying in the snow” that “Hamilton was killed in a duel with Aaron Burr, so Alexander Hamilton lying in the snow. Either Gregory read it or he figured out that it was a winter snowy scene.” Yet Morgan’s footnote helpfully clarifies that “the duel between Alexander Hamilton and Aaron Burr took place on July 11, 1804, not winter at all.” Even more amusing is the footnote on Ginsberg’s riffing upon the poem’s closing lines, “Children, have you not heard of my meeting / with Israel Hans, Israel Hans—”:

Israel Hans apparently was some figure of the American Revolution. Oddly enough, Corso was quite learned in old, funny history.

. . . He wrote [the poem] in Amsterdam in 1958 when we were all living together in a furnished room meeting Dutch poets. I guess Israel Hans had originally been Dutch, I think that was the connection, he was some sort of Dutch, Jewish American revolutionary. That’s how Gregory knew about it.

Morgan’s footnote wryly observes “The editor has been unable to find any reference to Israel Hans in historical documents.” Ginsberg’s blind loyalty to his dear friend is quite clear, and when it comes down to it, fully understandable.

Ginsberg clings to memories as the basis for much of his work, and his reminiscences undergird everything he relays in both these interviews and lectures. Key events of his life are told and retold throughout both books. One of these is the infamous story of a vision he had while reading William Blake’s poetry in the summer of 1948. In his lecture on the novel Go! by John Clellon Holmes, Ginsberg describes how Holmes usurps “like terrible hokum” his Blakean vision for quasi-fictional use. Here is Holmes, as Ginsberg relates, “describing my experience through his interpretation of what I had described to him,” with subpar results: “A vision! A vision! The words kept stinging into his consciousness like quickening waves of fever . . . It was love! he cried to himself. A molecular ectoplasm hurtling through everything like a wild, bright light!” Unamused, Ginsberg has no qualms pointing out the flaws in the passage: “my first reaction when I read it was one of cringing and embarrassment, that it had come out so corny or seemed so drugged and hallucinatory, pitifully creepy, in fact.” It’s interesting to compare it with Ginsberg’s own description as given in a Q&A session in 1976:

. . . as far as light—I had a sensation of that everyday light as becoming some kind of eternal light. So it was like an eternal light superimposed on everyday light, but everyday light wasn’t any different than everyday light! It was just, “the eye altering alters all.” My eyes, having altered, everyday light seemed like sunlight in eternity. So there was a sensation of awe, spaciousness, and ancientness as in some eternity, but actually people get that everyday.

With the recent deaths earlier this year of Joanne Kyger and David Meltzer, the circle of living Beat-affiliated poets continues to tighten. Although often relegated to the fringe of the spotlight, both Meltzer and Kyger (along with several others) are major figures in their own right whose work is substantial and influence far-reaching. Kyger is the ultimate Dharma poet if ever there has been one (her work represents an alert, daily practice of utter awareness) just as Meltzer is the real deal when it comes to being a Jazz poet (he was down in the cellars with the musicians from the get-go). If there is a glaring hole in Ginsberg’s lectures and interviews it is the discussion of such figures. Although Kerouac (including Neal Cassady by association), Burroughs, and Corso may be “the best minds” Ginsberg felt he had known, his self-absorption within his relationships to these closest pals falls far short of being any sort of a truly thorough “literary history of the Beats.” As entertaining and richly rewarding as Ginsberg’s thoughts are, avid readers will be best served by these works as but accompaniment to far deeper reading into American poetics of the era.