Michael N. McGregor

Michael N. McGregor

Fordham University Press ($34.95)

by Linda Lappin

Visitors to the Greek island of Patmos in the 1990s might have noticed a lean, lanky older fellow with baggy jeans and a goatee, sipping lemonade at cafés while chatting with fishermen or waiting in line at the post office with a bundle of letters in hand. Passing by his house atop the whitewashed stairs, you might have heard the tapping of his keyboard after lunch when he left the blue-shuttered windows wide open to let in the breeze and the cats. A reclusive person, but by no means a hermit, he kept up a copious correspondence with poets, editors, and admirers all over the world, publishing poems in venues from the New Yorker to New Directions. The islanders called him Petros, as in Saint Peter, the Rock, whom he had grown to resemble. His real name was Robert Lax. He was an experimental poet, lifelong confidante to Thomas Merton, and unofficial spiritual advisor to Jack Kerouac, and he traded a mainstream literary career for a contemplative life on the island where St. John had envisioned the Apocalypse.

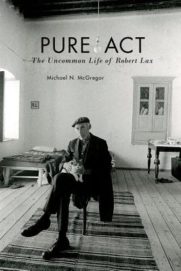

This unconventional soul is the subject of an insightful and generous biography by Michael N. McGregor, Pure Act: The Uncommon Life of Robert Lax. Inspiring and thought-provoking, it delves into questions still haunting us sixteen years into the new millennium: How to free ourselves from the materialism of our society? How to practice our faith and our art while keeping our bodies alive? The choices of Robert Lax followed the meanders of an all-consuming interrogation: how to live, love God, and be a poet, all at the same time. The answer lay in paring down the needs of daily life to the essentials, and stripping away the superfluous in his poetry to lay bare the innermost, authentic self.

McGregor traces Lax’ s origins as the son of Reform Jewish immigrants and his brilliant years at Columbia University where he forged friendships with Thomas Merton, Mark Van Doren, Ad Reinhardt, and many other artists and intellectuals. In this period, he also befriended a Hindu holy man in blue sneakers, Mahanambrata Brahmachari, who pointed out the path he was destined to take. No need to adopt a new religion if you feel a hunger for the sacred, the Hindu sage suggested: go deeper into your own tradition, which you will be better able to understand.

New York was a world hub of literary life in the mid 1930s, and Lax dallied in the bohemian atmosphere, reading William Blake and Christian mystics, talking philosophy and poetry with Merton until late into the night. Merton’s influence, the guru’s advice, and his own pondering of the Old and New Testaments would guide him toward a conversion to Catholicism a few years later. “The essence of religion . . . is to love the Lord with all your heart and all your soul and with all your mind or might and to love your neighbor as yourself,” he wrote. In 1943, Lax was baptized in the same church on 125th Street where Thomas Merton had been baptized five years earlier.

His early career touched all the milestones a young writer might dream of—a job writing for the radio, work as a reviewer for prominent newspapers, a position at the New Yorker, a stint in Hollywood as a researcher and screenwriter, employment at Time-Life, a teaching job in Chapel Hill followed by a prestigious fellowship—but none of this made him happy. At the New Yorker he was particularly miserable. The commercial aspects of the magazine and of Manhattan depressed him, he couldn’t hit the right tone to please his editors, and a war was on in Europe—it was 1941, and American involvement seemed inevitable sooner or later. As he brooded over the lack of peace and understanding in the world, his moral and social consciousness expanded. “All the world is wasting my time,” he wrote. “I know there are only a couple of things worth doing. Things like feeding the poor . . . Here I sit in an office doing nothing.”

During the grim years of the war, Lax sought solace by putting his faith into practice, helping out in Harlem at a Catholic charity, and later moving to a tenement to be closer to the people he wished to serve. It was here, McGregor tells us, that he began to see that “poverty—of many kinds—was the necessary ground on which to build the life he envisioned.” When Merton withdrew into a monastery, however, Lax chose a different path: a short gig with a traveling circus.

The circus had played a key role in Lax’s personal mythology ever since his childhood, when his father used to take him to watch the tents being set up at dawn whenever a circus pulled into town. The intrusion of the exotic into his sleepy hometown—(Olean, New York)—the gaudy colors, glamorous beasts, sleek performers in sequined costumes—stirred an excitement he never forgot. Invited to tag along with another New Yorker writer on assignment to interview the Christianis, a family of acrobatic bareback riders, Lax was drawn into their world, making friendships that would last a lifetime.

The camaraderie of the circus people and the simplified needs of life on the road strongly appealed to the young Lax, as did living on the edge. The circus performers threw themselves with a passion into daring, physical feats while remaining exquisitely balanced, mindful in a whirlwind of movement. It was the perfect metaphor for the inner presence he sought in life, and also for artistic creation. In his acclaimed cycle of poems, The Circus of the Sun, Lax would celebrate his acrobat friends as God’s chosen people whose eyes were “portals to a land of dusk.” During his brief time with the circus, he developed and performed his own clown routine and even learned to juggle. Then it was back to reality and the same old problem. McGregor writes:

The need for an income was the only thing standing between Lax and the life he wanted—that and a deeply American idea implanted in him in childhood and amplified at Columbia: that public recognition of one’s success is tantamount to being successful. . . . He would come to see that the alternative to increasing income is decreasing need and that success is interpreted differently if one’s primary audience is God. In this, as in so many important matters, his model was Brahmachari. It is better to have faith that what you need will come to you than the assurance of money in the bank, he wrote in his journal . . .

After the war, Lax set out for Europe, armed with a Brownie camera and a portable typewriter, eager to test how far his faith would take him. In Marseille, he found himself sharing rooms with a band of petty thieves. He intentionally sought out situations that forced him to confront his fears. In the Alps and in Rome, he was welcomed at monasteries and Catholic sanctuaries. From this point on, “the wandering and wondering became his life.” Eventually his wandering led him to the east Aegean, to the island of Kalymnos, and later to Patmos.

On Kalymnos, Lax came to know the sponge fishermen, whose lives in some ways resembled those of the circus people: their daring dives required physical control and mindful presence; myth, festivity, and danger infused their lives. Observing the island people at their daily tasks, Lax believed they had “found their center.” Still, all was not ideal. After living in Kalymnos for a while and falling so much in love with the place that he felt married to it, he discovered, to his horror, that many locals presumed he was a spy, and despised him for it. The political turmoil in Greece from Colonel Georgios Papadopoulos’s take-over in 1967 to the Turkish invasion of Cyprus in 1974 had created a climate that fostered such suspicions. On occasion his rooms were searched and his mail opened. One wonders what the authorities might have made of his vertical poems consisting at times only of colors, or a repetition of nouns, one syllable to a line. The poisoned atmosphere eroded his peace of mind, and with much regret he relocated to Patmos where he spent his final years.

Throughout his time in Greece, Lax’s literary reputation grew, partly thanks to his close association with Merton, whose autobiography and collected letters had made their friendship public, and partly to the recognition of his own achievements in avant-garde poetry. Shortly after moving to Greece in 1962, Lax had written in his journal, “This doesn’t sound like me at all, you say? Good. It’s cost me a terrible effort all these years to sound like me, and I’ve only now decided to give it up. That goes for looking like me, dressing like me, and preferring the kind of thing I prefer.”

Never once, though, did he consider giving up poetry. Expenses for international postage to send poems out into the world were as vital as food or fuel. “Reject slips are not supposed to build humility,” he wrote to poet Michael Mott, “Humility is truth: humility is recognizing your gifts as a poet and using them.”

Robert Lax divested himself of everything unnecessary in order to reach the place from which acts of true poetry might spring—that core of pure consciousness from which we witness the world. “Deeper than all the things he saw, was the watcher . . . deeper than all the things he heard, the listener,” he wrote, enjoining us to seek that same crystalline awareness and discover the poetry of our own lives.