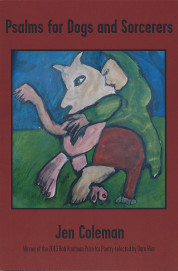

Jen Coleman

Jen Coleman

Trembling Pillow Press ($16)

by Jonathan Lohr

In an essay Jen Coleman wrote for the Poetic Labor Project website about her work at an environmental advocacy nonprofit, she said “In my job, I use the same words over and over: / Critical. Health. Action. Climate. Water. Toxic. Dollars. Strategic. Now.” This limitation of vocabulary creates a sense of aura around those words through repetition. How much of any given worship is a repetition of language? Chants, prayers, litanies, hymns, all carry with them an elevation of their subject through their anthemic nature.

Coleman’s Psalms for Dogs and Sorcerers very deliberately creates this sense of song through repetition. “Book Shield” opens with a heave of violence that is counterpointed with a bouncing delivery:

Bombings and battles and the war is over

with bombings and battles galore.

Waves of invasion and the war is over

behaving with waves of invasion.

The rhythm of the lines gives the sense of a post-World War celebratory jingle or playground chant, but when the poem says “the war is over,” it isn’t a celebration of peace, it’s a statement of the violence that has happened.

Images of human violence are delivered throughout the book by a dancing language. The use of lilting repetition might lead one to make comparisons to Gertrude Stein, but while Stein’s repetition works to cause distance between the word and the reader, Colman’s language works to develop within the reader a willingness to join in communion with the poem. This can be seen in “Soothsayer”:

You are the ward of a word and the word is you

who would stoop for a crumb of light.

You are born of a word and the word is flesh

and small as a snowflake, small as a pill,

a brain pill, a smart pill, a thrill pill, small

as a get thinner faster pill, a youngness pill

The poem envelops the reader, setting itself up as a textual deity with “the word made flesh.” But at the same time, the word is a small pill ingested by the reader, one that performs any sort of bodily or emotional task the reader might need.

Indeed, perhaps most striking about Psalms for Dogs and Sorcerers is how it deploys the body throughout it. The body is placed firmly within the world, within violence, within and around language, but the world in which it resides is never forgotten. Coleman’s poems create the lush ecosystem surrounding the body. “Doctrine of the Rude Dream,” a multi-sectioned poem, begins:

What the Milkweed Pod said:

What the Brain has bestowed

is the Rude Body;

this Rude Body is Naked.Naked may not be left for an instant.

On this account,

the Rude Body reaches wide and far

and yet is secret.

The Milkweed Pod is set up as an oracle figure speaking the riddled-truth of the body. The body is “rude,” harsh to the setting around it. Another reading of “rude” could be “of crude construction,” which points to the next poem, “Yellow Tower Crane,” a description of the toll that corporate construction takes on its surroundings.

Ultimately, Jen Coleman’s Psalms for Dogs and Sorcerers weaves a deconstruction of the body. The sense of worship in the poems isn’t placed upon the body, but like countless medieval treatises on the flesh, it creates a fluidity between what gives the body life and what takes it apart. During this dismantling, the reader realizes that all along the awe of the language has been pointing to the setting of the body, to the omnipresent and immutable world in which it is petulantly writhing.