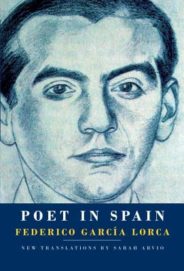

Federico García Lorca

Federico García Lorca

Translated by Sarah Arvio

Alfred A. Knopf ($35)

by Patrick James Dunagan

An enthusiastic, near universal adoration swathes the work of Federico García Lorca. Over the seventy-odd years since the tragedy of his assassination in 1936 by fascist troops of Spanish dictator Franco on charges of being socialist and homosexual, poetic attestations of intimacy with his work have arisen from many quarters in the States. Yet such impassioned attention does have its downsides. As Jonathan Mayhew protests in his critical reevaluation, Apocryphal Lorca: Translation, Parody, Kitsch: Lorca “has been Americanized beyond recognition, made to serve a variety of domestic interests.” He convincingly argues that “incomplete or misleading views” result from the attempt to essentialize Lorca’s work into a singular cohesive whole: “One of the traps in reading Lorca is the assumption that there is a central myth or conflict, a ‘master-narrative’ equally applicable to the early lyrics, the romances, the experimental theater, the rural tragedies, and the late poetry.” This is an unfortunate result of appreciation overrunning itself and transforming into unconscious action that enwraps and curtails.

Much of this enthusiasm originated early on from readings/translations of Lorca’s Poeta en Nueva York, written while the poet spent time at Columbia University (1929-30), and/or romanticized (mis)perceptions of his remarks regarding the dark Spanish force of artistic inspiration known as Duende. Sarah Arvio’s fresh translation of Lorca, Poet in Spain, enters into this situation with a title striking an apt counter-knock against the prevailing tide. While Arvio makes no mention of Mayhew’s Apocryphal Lorca, she does assert a division between Lorca’s New York poems (which she pointedly does not include here) and those written in Spain: “To my ear, these voices are so different they could almost be the voices of two different poets.” In this regard, her translation poses the possibility of serving as a corrective aligned with addressing Mayhew’s criticism.

Arvio’s translation, however, arrives with its own set of problems. One of these involves her decisions over selecting and ordering Lorca’s early poetry. She notes that Lorca wrote “mostly in sequences, and in sets of sequences,” yet that his Suites was not published until after his death and that consequent to having written the collection, as he was composing his second published work, Songs/Canciones (1927), he went back and “ransacked” through it for material to fill out the latter. Taking Lorca’s actions as liberty bestowing, Arvio performed her “own sorting and ransacking” of the earlier poems (in some cases leaving out a numbered section of a poem and arranging poems out of chronological order) presenting only Lorca’s later “sequences in full and in the chronological order of their composition: Gypsy Ballads, The Tamarit Diwan, Lament for Ignacio Sánchez Mejías and Dark love Sonnets.” While inclusion of these later sequences in full (along with a clutch of poems previously unpublished in English and a successful new English translation of Lorca’s powerful play Bodas de sangre/The Blood Wedding) is most welcome, Arvio’s freewheeled handling of the early work gives the collection an unbalanced feel and is thus less than ideal.

The other major issue involves Arvio’s punctuation, which also leans on an assumed liberty borrowed from Lorca. As she states:

I've used almost no punctuation; this was my style of composition. I felt that punctuating, as I worked, hindered the flow of the language. When I was done it was too late to go back; the poems had their own integrity and didn't need commas and periods. So I let them stand. I was fascinated to see, studying the manuscripts, that Lorca often wrote his drafts with little or no punctuation: a stray period, a comma in the middle of the line, an exclamation mark. He added on punctuation later; manuscripts published at the time of his death were punctuated by an editor.

The haphazard punctuation makes for varied results, at times reading more as a transcription of a translator’s working notebook rather than an authoritative text. Sometimes where Lorca has a period Arvio capitalizes the following word in the next line, or in the case of punctuation occurring within a line inserts an extra space as well (which is a solid practice), but at other times she doesn’t. Sometimes she inserts dashes but never in a manner leading to any discernible recurring purpose. Occasionally, though rarely, she carries a period over into her translation. She avoids all Lorca’s exclamations and question marks.

When considered comprehensively there is a lack of any coherent justification given for the discrepancies found in Arvio’s translation practice. This becomes a detracting nuisance, especially since when her translations are on, they are generally spot on. The imbalance is clear in the two closing stanzas of “Alma ausente/The Soul is Gone” part four of Lament for Ignacio Sánchez Mejías:

No te conoce nadie. No. Pero yo te canto.

Yo canto para luego tu perfil y tu gracia.

La madurez insigne de tu conocimiento.

Tu apetencia de muerte y el gusto de su boca.

La tristeza que tuvo tu valiente alegría.Tardará mucho tiempo en nacer, si es que nace,

un andaluz tan claro, tan rico de aventura.

Yo canto su elegancia con palabras que gimen

y recuerdo una brisa triste por los olivos.No one knows you But I sing for you

I sing for your chiseled face and your grace

and the great seasoned age of your knowledge

your craving for death the savor of its mouth

and the sadness in your valiant joyA long time will pass before another

Andalusian is born—if ever he is born—

so lucid and so rich in daring

I sing of his elegance with weeping words

and I remember a sad wind among the olives

The extra space and capitalization of “But” are successful, yet why not include the extra “No”? And while the rest of the stanza comes off well, the opening line of the following stanza is rendered in terribly prosaic fashion. At least the closing lines of the elegy carry across the melancholic remorse of the original. There is little doubt Arvio’s work would certainly have benefited from the scrutinizing eye of a worthy editor. There are times an author's (or translator’s) laissez faire attitude requires a fair bit of tethering.