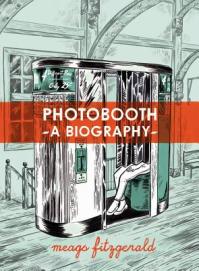

Meags Fitzgerald

Meags Fitzgerald

Conundrum Press ($20)

by Jay Besemer

Imagine yourself here, in a busy train station or perhaps a mall, staring with an odd and anxious longing at a vintage photobooth. Your heart lurches with the thrill of the forbidden, or something like it—as if you’re about to do something your parents wouldn’t approve of. Taking a deep breath, you walk into the booth. You sit down carefully, pull the curtain shut firmly, adjust the backdrop behind you. You insert your money and press the button, slightly euphoric, slightly hopeful, slightly embarrassed. The red light comes on. The reflective glass tells you HOLD STILL in no uncertain terms. Do you? No time to decide on a strategy, a pose. The light flashes, the shutter opens and closes with a cough, and your photobooth adventure begins. Each time is different, unique, special.

But what’s so special about photobooths? Where did they come from, and why are they disappearing? Who cares? These questions and more are addressed in Canadian artist Meags Fitzgerald’s graphic “novel” Photobooth: A Biography. More accurately described as a mixed-genre graphic nonfiction that combines elements of history, autobiography, travelogue, and long-form personal essay, this unique and fascinating volume tells nested stories stemming from the author’s love of and work with classic analog wet-chemistry photobooths. Both deeply personal and fiercely public-minded, Fitzgerald’s book takes readers through the origins and transformations of the photobooth all the way through to its present-day decline. Fitzgerald’s prose interweaves an engaging historical-technical exploration of the booth with an examination of her own—and others’—more subjective creative, emotional and experiential relationships with this technology. Her rich, precise and inviting pen-and-ink illustrations make readers feel they are beside her in the booths, accompanying her on an international quest to investigate and save this endangered species.

Photobooth is organized into three sections with a prologue. The prologue sets the stage, establishing both personal and public context. Here we are reminded that even as recently as 2003, “We didn’t carry hundreds of photos of ourselves everywhere on our phones. Social media didn’t exist as a concept yet.” This is vexingly easy to forget. Our relationships to images have changed dramatically—perhaps traumatically—in the last decade, and that change is both mental and physical. Part of Fitzgerald’s argument is that the physicality of our older image-making technologies, and of the photobooths themselves, deserves to be honored—ideally, to be preserved. If preservation is impossible, the total loss of the analog booth could have a wide-ranging cultural impact.

This could happen sooner than we think, and we’re shown why on page seventeen:

The paper for colour photos stopped being made in 2007. The stockpile is being used up and is projected to be gone by summer 2015. Currently, there is only one supplier in the world still making the B&W paper, if they stop photobooths will disappear from public places entirely within five to ten years.

Wet-chemistry booths in the EU face an additional threat if the chemicals used in their developing tanks become banned, which could happen in 2016. These circumstances account for the sense of urgency that permeates the book, and helps explain why Fitzgerald devoted so much of her recent life to this labor of love.

Part I launches into a serious socio-historical exploration of the photobooth, where we see the evolution of the technology itself alongside the social uses to which it is put. During the Great Depression, the photobooth allowed those hardest hit by economic disaster to make dignified, high-quality portraits and self-portraits at affordable prices. In the Second World War, many of those serving (on both sides) chose to photograph themselves in booths before reporting to duty, or coming home, or in other situations. And as spaces not affected by segregation, photobooths were accessible to African Americans in a way that many photo studios were not. Additionally, the privacy of the booth gave queer couples a safe place to be themselves together, confirming and celebrating their intimacy. The self-serve photobooth “allowed people to document themselves as they wanted to be seen and as they saw themselves.”

Part II of Photobooth: A Biography moves from general booth history to more specific histories—those of the people whose lives are deeply imbricated with the history and fate of the booths. Fitzgerald’s real quest emerges here. This is where the narrative goes on the road, becoming at once deeply personal and passionately social. The deeper shift into more subjective territory is quite riveting, even exciting. We begin to understand why personal stakes in the analog photobooth are so high for Fitzgerald and for many of the people she visits.

The relationship and the tension between digital and analog technologies is never clearer than in these pages. Fitzgerald depends upon email, social media tools and Web communities like photobooth.net to navigate and plan her international journey, and this irony is acknowledged. Yet the face to face connectivity detailed in the book—and even the very premise of traveling all over the world to engage with and touch other booths and boothers—seems directly opposed to the limited range of interactions possible in social media contexts. The act of touching is crucial here. It is one element of the complex social and behavioral context of booth use that can’t be replicated by smartphone cameras or the “fauxtobooth” function (my term, not Fitzgerald’s) on some laptops.

In the end, though, there comes a time when we have to say goodbye. The penultimate page of the story offers a resolution of sorts:

I felt like I chose to love these things that couldn’t really love me back, not because they’re inanimate, but because they’re just too preoccupied with their own extinction. . . . I was overcome with gratitude. I knew that it didn’t really matter what happened next because everything had already been worthwhile.

Whatever does happen next for chemical photobooths, the journey of Photobooth: A Biography is certainly fulfilling. Fitzgerald’s love comes through loud and strong; love of photobooths, certainly, but also love of the people in her life, boothers or not. This is a must-read book for fans of graphic-genre narratives, photographers, pop-culture historians, scholars of human relationships to our technologies, and anyone who loves a good dip-n-dunk.