photo by Mark Von Holden, Getty

by Sean Smuda

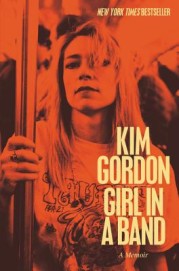

Originally published in 2015, Kim Gordon’s memoir Girl in a Band (Dey Street Books, $16.99) has been getting me through the 2020 plague in the way that Punk’s attitude was born to do. Gordon’s attitude in her writing, and in life, is to achieve strength from a position of weakness; she is honest, factual, political, and compassionate in a genre where many are not. And just as Sonic Youth’s standing waves of noise and fragmentary lyrics entwine mystery, obsession, and violence, pushing through and beyond them to deeper connections and freedoms, this book both is and is not Rock. After years of seeing and following the band, I had burned out and into other musics, but COVID-19 and living outside the U.S. rustled the desire and opportunity to re-trench to a pre-internet world and to think about its future.

Gordon’s story is highly apt for a present in which we are all vulnerable and missing parts of our lives, thinking about how they could be different and how they are going to continue. The first time I saw her with Sonic Youth was at Folk City in New York, after hitchhiking there from Minneapolis via New Orleans and Athens. My companion and I had put up with too much Top 40 radio in our rides, so on spotting a notice in the Village Voice about a band that played with screw drivers and non-rock tunings, we were sold. Straight from recording their second album, Bad Moon Rising, the band set up on the peripheries of the small room with two drummers and Super-8 movies of the LA desert. They surrounded and engulfed the audience with dissonant rocking trance, and the finale, “Death Valley ’69,” invoked America’s S&M signposts from the outside in. Disaffected as if staring down ghosts, Gordon gave the impression of being alien, distanced, and under great burden; in this book she owns it and fleshes it out.

Throughout Girl in a Band, Gordon’s consciousness of the difficulty of family dynamics and individual fragility resonate. Hers is a clear line from a childhood conflicted by admiration for and emotional abuse from a paranoid schizophrenic sibling, to a maturity that evenly deals with spousal betrayal. She re-orders the dominant into the equitable, and writes of how hard it is to make emotional space around people, especially when this is perceived as being removed. She also explores (ironically) how the Germans have a word—Maskenfreiheit—meaning the freedom conferred by masks. Performing is a space in which she can be both brave and vulnerable, masculine and feminine, and switch.

Throughout Girl in a Band, Gordon’s consciousness of the difficulty of family dynamics and individual fragility resonate. Hers is a clear line from a childhood conflicted by admiration for and emotional abuse from a paranoid schizophrenic sibling, to a maturity that evenly deals with spousal betrayal. She re-orders the dominant into the equitable, and writes of how hard it is to make emotional space around people, especially when this is perceived as being removed. She also explores (ironically) how the Germans have a word—Maskenfreiheit—meaning the freedom conferred by masks. Performing is a space in which she can be both brave and vulnerable, masculine and feminine, and switch.

Gordon’s witnessing of cultural changes since the Reagan era taps the country’s spirit, and she shows in both life and art how beliefs firmly presented counter business-as-usual: take the proto-#MeToo song, “Swimsuit Issue,” or her deconstruction of body image, “Tunic,” or one about the ambiguities of coming from Westward Expansionist stock, “Brave Men Run”. In her writings, she further notes the contradictory fascinations of gender, "guys who have crossed their guitars together, two thunderfoxes in the throes of self-love and combat, that powerful form of intimacy only achieved onstage in front of other people, known as male bonding." To embody such nuances in these “re-open it” days seems impossible.

In a post-internet world, the heroics/transcendence of the entertainment industry are at a rhizomatic level, a place where Gordon and Sonic Youth were always at. Despite the end of band and husband, she continues to represent and push ideals—ones that give the middle finger to a system that capitalizes on fake news and class and race difference through viral dissonance. The clarity and pointed anger with which she details her changes is epic and incisive, boomeranging from the Beats to now. Her current art projects and band, Body/Head, poise images and slow time down to work with meaning as something physical, ritualized, dance-like. At this point, I think we can all relate. Coupled with her music’s limpid, driving cosmos, Girl in a Band is far away and close, drawing the reader to the now of reckoning and ecstasy.