by John Toren

by John Toren

As Covid-19 forced us all to spend more time indoors last spring, I found myself drawn more than ever to simple, earthy prose. Homespun descriptions of rural life offered an effective counterweight to daily death tolls and the homicidal plotlines of standard streaming fare. I steered clear of the environmental harangues that are so common these days (important though they may be), and I also avoided narratives of wilderness adventure, which tend to focus on human endurance and close calls with disaster rather than the supple and harmonious interactions of living things.

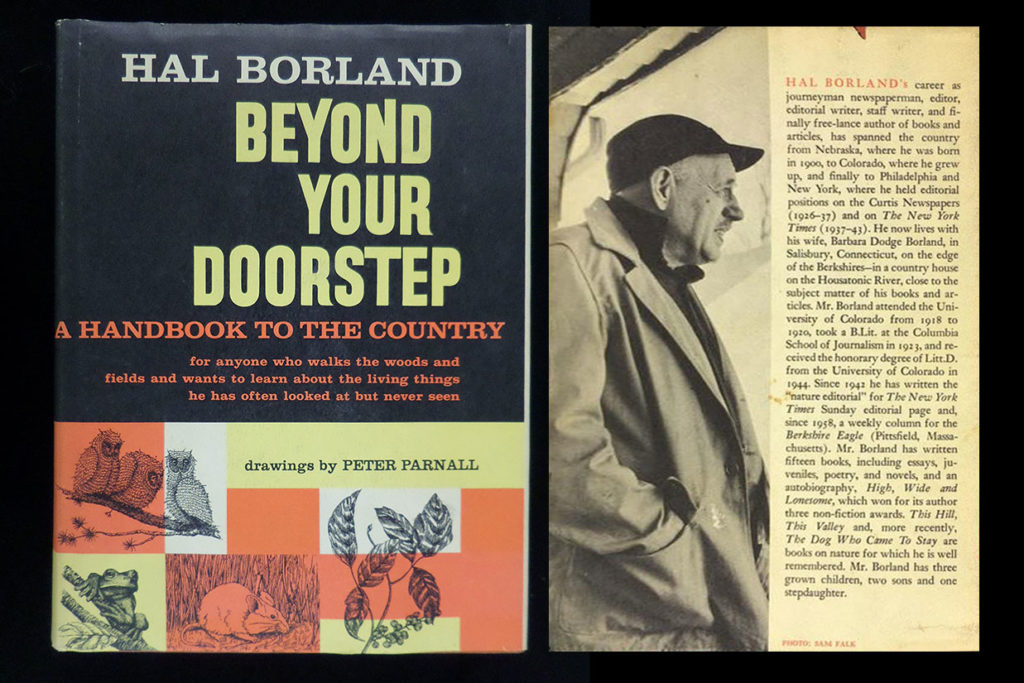

Perhaps I'm isolating a narrow slice of experience here, but I had no trouble finding things to satisfy the need, from children's books (Selma Lagerlöf's The Wonderful Adventures of Nils Holgersson) to fiction (Jean Giono's Blue Boy) to reappraisals of agricultural history (James McGregor's Back to the Garden: Nature and the Mediterranean World from Prehistory to the Present) to memoir (Swedish entomologist Fredrik Sjoberg's wide-ranging essay The Fly Trap.) But the book that perhaps offered the most satisfying read was Hal Borland's Beyond Your Doorstep: A Handbook to the Country.

Alfred Knopf published the book back in 1962, but I spotted a pristine copy of the first edition just last summer at Beagle and Wolf Books, a small but well-stocked shop in Park Rapids, MN. The front endpaper carries an inscription to “Alice and Hamlet, from Plummer and Ida, Dec-25-1963,” written with a fountain pen in elegant cursive script that resembles my mother’s handwriting—and that of many other women of her time. Although by 1962 Knopf had been sold to Random House, the book is decorated with the same sort of wing-dings we find in earlier Knopf editions stretching from Sigurd Olson's canoeing essays back to the famous works of Wallace Stevens, Willa Cather, and Thomas Mann.

To judge from the lack of wear, I don’t think Alice and Hamlet ever got around to reading the book. Borland describes it in the foreword as a handbook rather than a field guide. His goal is “to indicate what to look for and where and when.” If he inspires the reader to move on to guide books for details, then Borland will consider his purpose to have been fulfilled.

Perhaps he was being modest, but such a précis fails to account for the intrinsic value—I’m tempted to say the “poetry”—of the prose itself, which draws on both the author’s vast knowledge of the natural world and his relaxed, slightly folksy New England tone. Though he wrote regularly for the New York Times, Borland spent much of the year on his farm in northwestern Connecticut.

Borland makes it clear early on that he knows the names of the trees, the bugs, and the fish, how they interrelate, and where they’re likely to be found. Excluding genuine wilderness from his purview, he focuses on phenomena that anyone in the eastern United States might easily come upon during a two-hour hike down a country road or fifteen minutes in a barn. To dip into any of the first six chapters, which range from “Pastures and Meadows” to “The Bog and the Swamp” and “Flowing Waters,” might be the next best thing to actually taking such a walk.

Come mid-April and the shadblow blooms in the riverside woods like tall spurts of shimmering white mist among the leafless trees. I first knew shadblow in the high mountains of southwestern Colorado, which simply proves how broad is the range of this cousin of the apple. But I knew it there as serviceberry. In the Northeast it gets the name shadblow or shadbush because it comes to blossom when the shad come up the streams to spawn—or did come when the streams were habitable for shad, not heavily polluted. It blossoms in tufts of small, white, long-petaled flowers before the leaves appear.

As an aside, the name “serviceberry” also has a New England derivation: The tree blooms in the spring at just the time when the ground has thawed enough to make it feasible to conduct funeral services and bury those who had died the previous winter.

At a few points later in the book, Borland’s attention veers off in less personal directions, as if his editor had told him, “Hal, you’ve got to write a chapter on the night sky. And how about one on foraging? And poisonous plants?” We don’t need to be told that the five major planets are Mercury, Venus, Mars, Jupiter, and Saturn, for example. To his credit, in the section on foraging Borland describes quite a few edible plants, one after another, but doesn’t shrink from admitting that most of them taste terrible or are not worth the effort required to gather them.

The chapter on birds also seems a little weak, though it runs to twenty-eight pages. Borland clearly knows his birds; he mentions that in the course of a given summer he is sometimes able to distinguish between five individual Baltimore orioles on the basis of slight variations in their song. But he spends less times sharing his encounters with the warblers, vireos, flycatchers and raptors in the woods around his farm than assuring readers that birding isn't as hard as it may seem, and encouraging them to buy binoculars.

All the same, there are a few things to be learned or enjoyed on nearly every page of this welcoming and erudite ramble across the New England countryside. And near the end of the book, Borland draws upon all the lore he's been sharing to take us through a brief tour of the passing seasons, month by month. As a wrap-up, he devotes an entire chapter to the issue of common versus scientific names, and provides a long list of equivalents.

Shadblow? Serviceberry? We’re talking here about the Amalanchier canadensis.