by Sparrow

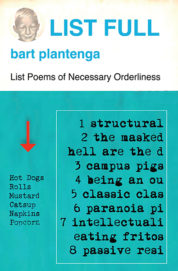

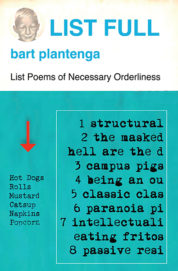

Born on the edge of Amsterdam, bart plantenga has lived in many places, including New York City and Paris. Though he has been writing lists since the age of nine he began writing other creative work in high school, and he has since published novels, poetry, short stories, essays (hotheaded and otherwise), and the definitive nonfiction works on yodeling (Yodel-ay-ee-oooo: The Secret History of Yodeling Around the World (Routledge, 2003) and Yodel in Hi-Fi: From Kitsch Folk to Contemporary Electronica (University of Wisconsin Press, 2013)). Also an innovative radio disc jockey, plantenga has produced the weekly program Wreck This Mess since forever on stations in New York (WFMU), Paris, Amsterdam, Rotterdam, and currently on Mixcloud. He eventually moved back to Amsterdam in 1996, where he lives with his partner and daughter to this very day. His newest book is List Full: List Poems of Necessary Orderliness (Spuyten Duyvil Publishing, $18).

Sparrow: Are the rules of list poems different than the rules of ordinary poetry?

bart plantenga: Yes, as different as the rules for admittance to an S&M club and those for Harvard Law School. The list does something a poem rarely does, unless you’re a practicing Surrealist: it allows chance and unconsciousness to rule rhythm while allowing the chore, grocery item, or reminder to determine the line break. There is NO preconceived narrative framework. If you discover a story in any of the lists, consider yourself a creative apophenic collaborator.

A poem hopes to mean, to move, to reach the heart, while a list can only mean in the same way a hammer or saw means something. The list can only arise from its “mere” utility by the employment of apophenia or placing it in a new context. The irony or hypocrisy or confusion is this: Lists are designed as small gestures of control in a world resistant to comprehension. So, the seemingly feckless list usually regiments—until it’s placed in contentious contrast with the lofty poem, where it can with its audacious leaps of logic and faith make a shambles of the prescriptions contained in the standard Poetry User’s Manual.

Sparrow: Did you worry that a book of personal lists was too narcissistic?

bart plantenga: We’re all busy with ourselves. If we can step out of our constrictive, perhaps attractive, costumes we might realize that, although unique, we’re a lot like other people, too. The lists in List Full display the mechanics and strategies we all apply to messy lives in need of structure and reason. In some ways, List Full may build a warmer campfire to gather around than, say, a non-list-based book of poems. Lists are universal, but they were never intended to display any locutionary prowess. They’re inhibitionist, not exhibitionist, not spawned from ego—although their curation may reveal an ounce of conceit.

bart plantenga: We’re all busy with ourselves. If we can step out of our constrictive, perhaps attractive, costumes we might realize that, although unique, we’re a lot like other people, too. The lists in List Full display the mechanics and strategies we all apply to messy lives in need of structure and reason. In some ways, List Full may build a warmer campfire to gather around than, say, a non-list-based book of poems. Lists are universal, but they were never intended to display any locutionary prowess. They’re inhibitionist, not exhibitionist, not spawned from ego—although their curation may reveal an ounce of conceit.

S: While writing were you thinking of Frank O’Hara, who’s always dropping the names of his friends in his poems?

bp: No, but I do like Frank and read him more often than other poets. It’s interesting that you noticed familiar names in some of my lists. I didn’t notice this aspect until I’d actually selected the lists and placed them in the layout. But the lists do, now that I look at them, create a certain O’Hara-like titillation—like gossip as high lit. Celebs in lists are like stars in the sky, and lists telescope that haughty distance between names, shrinking the universe. O’Hara, by the way, managed to write both modestly and majestically, being both humble and swaggering—a state of literary grace in my mind.

I’ve had discussions about O’Hara with Jose Padua. But I’d forgotten some of the reasons why I liked his poems so much:

- his lists delight in a clanking clash of disparate objects strung out joyously;

- he delights in creating disarray through a miscellany;

- while trying to make sense of something ordinary;

- plus he displayed an almost Dadaist/childlike giddiness in vocalizing a list of things in, for instance, the poem “Today”: “kangaroos, sequins, chocolate sodas . . . pearls, harmonicas, jujubes, aspirins”;

- this kind of list perks the ears to fresh amalgams of objects never before presented side by side.

This is what lists can do: surrealistically and unconsciously juxtapose disparate words and objects that insist on new links, new syntactical molecules, creating fresh sound/poetic possibilities for the poem that is beyond meaning, beyond itself—a kind of Dada without the outrageous costumes. William Logan listed the poetic crimes of O’Hara’s poems as: “their giddiness in the face of despair, their animal pleasure in gossip, their false bravado, their frantic posturing and guilelessness and petty snobberies.” That’s about right.

S: Do you think the pieces in List Full are actual poems, or anti-poems?

bp: Neither and both. They were not created with any high purpose of changing the world or a contrarian purpose of bending poets out of shape. Lists hold words that can re-establish some sanity in an insane world. And yet, in their function of bringing order, making sure our thoughts and deeds get parked between the white lines, they also misbehave enough to upset an applecart and so, they are now framed as “what if we were to see them as poems,” something that may annoy some poets, but amuse others. Eventually their purpose evolved as texts to toss up against the inflated claims made by some poets about the paradigm-rocking power of the—or their—words.

Anyway, that’s how I came to describe them as unselfconscious, working-class poems of humility and utility. If I’d defined them beforehand as something high-minded like poems written to change the world and then began writing these lists with the shadow of that flapping hifalutin banner overhead, the result would have been a book full of hypocritical imposters and annoying wannabes, like rock ‘n’ roll poseurs trying to do jazz.

I see it this way: band A struggles for years to write a perfect pop hit and never manages to do so, while, in another garage, band B simply lets the juices flow and just like that, a miracle, they’ve produced an international hit. “The Piña Colada Song,” for instance, was recorded in one take and the Beastie Boys’s “You Gotta Fight For Your Right To Party!” was written in five minutes. This kind of miracle will seem unfair to all those artists who spend ages tweaking their sound, remixing, rehearsing, using a rhyming dictionary to get the lyrics right and then failing to ever crack the top 100. Maybe the list is to the poem what the Beastie Boys are to Yes or ELP.

This makes great poetry all the greater, because it avoids the minefield of presumed pomposity, of poems being somehow inherently better equipped to confront a corrupt and hypocritical society than ordinary texts. Take Amanda Gorman’s poem—don’t get me wrong, it’s a fine piece of patriotic, inspirational verse, but the rip tide of expectation that ensued removes “The Hill We Climb” from all effective heart-to-heart communication as it assumes its rightful position as fetish item, as consumable good, as rousing stump speech.

So, the list is not so much an anti-poem as a Buddhist go-round to the “self is an illusion” notion where self-consciousness destroys the very feedbed of poetry—spontaneity which magically allows the out-there to communicate with the in-here. I don’t know where I got this Thomas Merton quote from, but I had it written down and can here illustrate how erudite I am: “We cannot achieve greatness unless we lose all interest in being great. For our own idea of greatness is illusory, and if we pay too much attention to it we will . . . seek to live in a myth we have created for ourselves.”

S: Do you have a favorite poem in the collection?

bp: Yes, a couple: while clearing out my mother-in-law’s attic upstate and prepping the house for sale I came across Nina’s “Summer Things To Do,” which lists all the things a young, carefree girl might like to do in the summer of her 12th year (“bike ride with lunch,” for example). And the long list “Paolo di Prima Packrat Treasure” details just some of the thousands of other bizarre items I found while clearing out that attic. A friend of my mother-in-law, a charlatan dandy, was moving from NYC to Switzerland and transported ALL of his earthly belongings up! Two hundred and fifty boxes of treasure and junk, which I, in my own way, unpacked and laid end to end in order to create a biography of this shifty man of many aliases. So those are two.

S: What would you tell a young person who wants to write a list poem?

bp: Don’t. Lists are not conducive to conscious application of poetic demands. Lists are humble and utilitarian. Innocent. Written to structure your week. The list is the backhoe of literature. Any presumption of a list to being greater than itself—let’s say it begins to believe itself to be a Lamborghini—will spell instant disaster for the list.

S: Were you thinking of Walt Whitman?

bp: After the fact, yes. So after the fact that I forgot to mention him in the intro. I know that all great bardic blowhards recited in long, unbroken sentences of list-like cadences, and that list-like quality certainly gives some of Whitman’s poems an incantatory power, more vivacity.

S: Do you like Whitman?

bp: Of course. Whitman used lists as a rhetorical/rhythmic device where something not especially important gains a new life in his incantational context. Maybe these lists of his were a shorthand way to capture many of humanity’s details in one poem—like rapid-fire images in a movie trailer, feeding into our optic insatiability and our capacity to absorb a story much more rapidly than previous generations. Whitman was essentially writing scripts for today’s videos with his quick flip through hundreds of images.

I remember working for the US Census Bureau in 1976, biking from door to door in Ann Arbor and the country surroundings. Being on a bike, I was faster than the others, and so I gained down time to pull out my Leaves of Grass. I remember how magical it was at a young age to be reading it in that environment (“Give me a field where the unmow’d grass grows . . . give me serene moving animals”). Those were heavenly days of work, exploration, and poetic down time allowing me to witness Whitman’s words mingling with the scent of dry reeds, of fertile, wormy soil and the breezy sway of long-necked grasses.

S: Who’s your favorite poet?

bp: Well, I can never keep it to one: Brecht, O’Hara, Padua, Italo Calvino’s Invisible Cities, which is not poetry, per se, but reads like geographical poetry.The lyrics of the Fall’s Mark E. Smith and also Captain Beefheart. Ed Sanders’s Whitmanesque books. There’s Rimbaud’s Illuminations, Baudelaire’s Paris Spleen, and Breton’s Nadja, all three of which intravenously informed my Paris Scratch (Sensitive Skin Books, 2016). Diane di Prima’s Revolutionary Letters, Serge Gainsbourg’s lyrics, Karen Garthe’s The Haunt Road. Her work is excruciatingly, elegantly difficult, starkly and playfully obtuse and, in some ways, reminds me of Thelonious Monk’s piano playing.

S: Have you always made lists?

bp: Well, not “ALWAYS,” as in since I was born. But, yes, I began at an early age as a nerdy immigrant who wanted, ironically, to be SO American that I began making long lists of everything in which the US excelled such as—I don’t know—tire manufacturing, corn production, sitcoms, Olympic medal counts, nuclear warheads, tallest buildings—proving that my parents had indeed chosen the world’s best country. That’s what I thought until Vietnam, the race riots, and the generation gap shook things up for me and I became radicalized, anyway.

S: Speaking of being radicalized, do you worry that your books aren't political enough? I constantly do (about myself, I mean).

bp: Yeah, that’s a tough call. There’s already plenty of political books that are navel-gazing, wellness prescriptive, so correctly and uprightly constructed so that there is no dirt or doubt clinging to them. Or they’re written by committee and formally approved, so come out like filtered water rather than spring water. There are also the outright declamatory, hamfist in the air poems, declaring revolution in rhyme with a bit of googled reading as context. I hope there is a middle ground—words with a bit of class consciousness revealed without shoving the obvious prescription in your face—showing not shouting—poems that can still frolic in the sheer joy of sound or can be radical or antithetical to current trendy trendiness in their mere construction—so somewhere between Brecht, Dada, Di Prima, Run the Jewels, Gil Scott-Heron, and the Fugs. I hope List Full, in its working-class-ness, can out the poems we see in so many journals as bourgeois decorative devices, as distractions and diversions. That’s not to say I don’t read a lot of beautiful conventional poems! I want the revolution the Situationists dreamed of, one guided by the imagination, not a political party or a movement run top-down by heroes or spokesfolks. Being, not buying. Something like that.

S: What sort of order are the items in? They don’t seem to be in chronological or alphabetical order. Is it all a matter of euphony?

bp: The items in any one list are not orchestrated to create meaning. They serve an internal need to order my part of that world. In the book, the lists themselves are not ordered or curated. The originals had no awareness that they would ever be part of an ulterior purpose. The lists within the book are only mildly arranged so that some of the more personal ones referring to my youth or identity appear near the beginning. But I did not set out to create a biographical, timeline-ish meta-narrative. It is similar to my books Paris Scratch and NY Sin Phoney in Face Flat Minor (Sensitive Skin Books, 2017): they’re supposed to gain spark through jarring juxtapositions and surprising encounters, ignoring any composed linear time passage.

S: What is it about last meals of murderers on death row that fascinates you?

bp: The ridiculousness of the gesture. To quote from my own intro: “it is about the self-aggrandizing humanizing of the executioners & prison officials.” I have often imagined this final symbolic interaction between those going on with their lives and those about to die, a small ceremonial kindness at the juncture of where it meets extreme cruelty—a cruelty that most nations have eliminated from their repertoires of punishments. But it also offers the prisoner one last chance to present a final artwork, an installation comprised of a constellation of food choices.

S: What do you want for your last meal? (Personally, I think I would ask for Reese’s Peanut Butter Cups.)

bp: It would depend on the level of the prison guards’ bastardliness. If they were cruel, I’d eat something that would give me diarrhea, so that after they pull the switch and after my last twitch, I would leave behind a smelly mess. If I am innocent and some of the guards were sympathetic during my stay, I’d order some snack foods like nuts or M&Ms or croutons and spell out a message on my tray claiming my innocence and offering the name and number of an investigative journalist. Or I’d draw a smiley face in Skittles for them.

S: Do you know if these condemned men actually ate all this food they ordered?

bp: In fact, a number did not—they ordered absurdly elaborate meals and then ignored the meal as a “screw you,” to piss off the guards and prison officials one last time. White supremacist Lawrence Brewer placed an incredible order: “2 chicken fried steaks with gravy & onion, a bacon + triple cheeseburger, cheese omelet with beef, tomatoes, onions, bell peppers & jalapeños, pint of ice cream & peanut butter fudge + crushed peanuts + 3 root beers,” which he then proceeded to reject. He had been sentenced to die for his part in the gruesome Texas murder of James Byrd. Brewer and his mates picked up Byrd and drove him to a wooded area where they beat him up, spray-painted his face black, chained him to the bumper of their pickup truck and then dragged him for some 3 miles, effectively lynching and mutilating him beyond recognition. Brewer’s untouched meal was discarded, prompting Texas officials to terminate the last meal tradition.

S: Do you ever have the urge to make a more abstract list, like a list of all the times you doubted the existence of God, or a list of every time in your life you’ve gotten lost?

bp: I DO. And sometimes when I am hopelessly lost I go through a few of my tower of journals from years gone by and discover lists of some speculation or trepidation that seem so alien to me I cannot imagine having written them. But there they are in my journal, in my own handwriting.

S: Are the “Journals to Subscribe To” real?

bp: No, they—The Proceedings of the Retired Circus Dwarfs Federation, Papercut Survivors of Wilmington, Delaware Bimonthly—were composed with my friend Brad Lay in a riffing moment of temporary unhingedness with no intent to include it in List Full, which, at the time, did not yet exist. But this kind of exercise of trying to out-absurd our absurd reality usually comes back to haunt. Originally, we think we’re pretty clever—humorous even—only to discover there ARE titles like this in the new world of hyper-minuscule niche marketing. The conundrum: the more absurd our concoctions, the more likely we are to discover they already exist and that there are acolyte-members living by their credos.

S: Most lists we make are entirely rational: things we want to do, foods we want to buy. Taken out of context, they become quite strange—especially since we tend to read texts before looking at the titles. Some of the ones in List Full don’t even have contexts. We never know exactly what they are.

bp: Yes, nice that you noticed this. This may be one of the key raison d’etres of List Full. The lists gain sustenance—I hope—by the broad leaps of faith, the wide gaps in meaning from line to line, which forces our brains to create meaning and that is exactly what we do. And so the poems are composed with the help of the suspension-of-disbelief reader. There was no meaning until ascribed by necessity. This is known as apophenia. Apophenia is fascinating: it’s the tendency to (mis)perceive connections and meanings between unrelated things. A kind of Rorschach test, maybe.

S: Are there any you wish you’d put in, that you left out?

bp: A scoop: I will be adding a new list to an update of List Full that’ll consist of a selection of all the odd Dutch names I’ve collected over the years. It all began with a Frenchman, Leopold Fucker, discovered in the Columbarium in Pere Lachaise when I lived there. The list doubled with my first Amsterdam job, painting the offices of a filmmaker named Ruud Monster. I’ve added some 200 since and will use about 50. A few others: Fake Krist (an NSB—Dutch fascist—officer during WWII), Henk Leegte (Emptiness), Harry Cock, Tiny Cox, Tiete van de Laars (Tits of the Boot), Jan Rotmensen (John Shitty People), Joke Butter, Constant Dullaart (a young artist)… See, here I go, the mere listing and reciting of these names brings me great oratory delight.

S: One big question with lists is whether to number the items. What’s your opinion on this? Most of yours are unnumbered.

bp: I like numbered lists because they express an extra level of ranking control—#1 should be performed first. In a situation where that control may have been difficult to secure, the number acts like an anchor. Numbering can also add an extra dramatic countdown element. Ultimately, the number, like the bullet point, is just another tool in the list’s toolbox.

S: Let us confess that we are both members of The Unbearables, a ragtag group of poets and shameless novelists who formerly met in dive bars of the East Village (of Manhattan) and are now spread throughout the world, you in Amsterdam, me in Phoenicia, New York, etc. Do The Unbearables influence your work?

bp: If inhabiting is influencing, then YES. I am a cannibal of the misremembered past, and so many of The Unbearables have appeared in thinly disguised or barely recognizable forms in my stories over the years. Many of the lists are also inhabited by their Pac-Man-like presence. Hint: The Unbearables tend to a kind of enlightened buffoonery and often renounce their own identities, taking on the forms of avatars in their own image. An index matching fictional to actual Unbearable characters is available for a steep price, although a discount is offered for those offering genuine-sounding praise.

S: Has anyone written a poetry book of lists before?

bp: There are a lot of list poems out there. In most cases, they seem quite unconscious and are deemed poetry after the fact. Those are probably the best. The documenters or “authors” tend to be fine with filing them in the category of “amusing things you can do with words.” There are several books out there too, but they seem to be mostly instructional and geared towards the notion that lists are a relaxed-fun way to get kids over their fear of words or poetry. So that’s revealing right there: lists as propaganda for the joy of words.

Click here to purchase this book

directly from the independent publisher

Jenny Qi

Jenny Qi

by bart plantenga

by bart plantenga