by Chrissy Kolaya

Writer, publisher, and community builder Ryan Rivas is a familiar face in the Florida literary community. As the founder and publisher of Burrow Press, Rivas has focused not only on developing a press devoted to taking artistic risks, but also on working to cultivate literary community by launching and supporting an impressive number of fun and creative literary events in and around Orlando. As Coordinator of MFA Publishing at Stetson University’s MFA of the Americas creative writing program, Rivas is working to inspire a new generation of students to develop their own literary activism. Rivas’s own writing has appeared in The Believer, The Rumpus, and Best American Nonrequired Reading 2012, and has been recognized with a fellowship from the Macondo Writers Workshop, which supports writers engaged in activism.

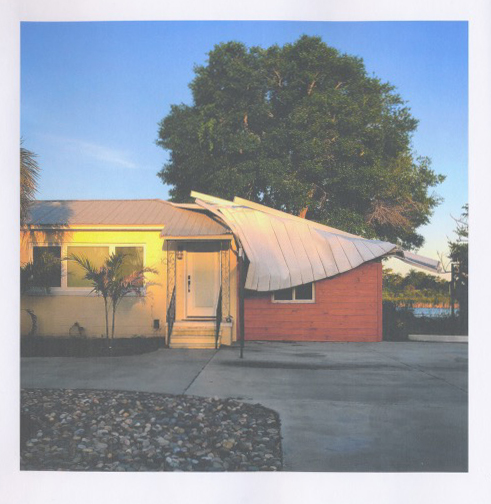

Rivas’s debut book, Nextdoor in Colonialtown (Autofocus Books, $26), is an innovative pairing of photographs of Orlando’s Colonialtown, the author’s neighborhood for the last decade, juxtaposed with text from the area’s Nextdoor.com posts. The book is at once an exercise in examining one’s home and a powerful commentary of the role attitudes about land, property, race, and fear have played in the development of many of our country’s suburban communities.

Chrissy Kolaya: What can you tell me about where the idea for this book came from?

Ryan Rivas: During the worst of COVID and while I was at work (still am) on what I think of as a “suburban gothic” novel, I started taking pictures of my neighborhood on my phone while I was out running. I am preoccupied with aspects of the gothic in relation to Whiteness, and maybe this led me to stop and document these innocuous and strange things. (Also, as a begrudging runner, I appreciate a good excuse to stop.) I started posting these photos on Instagram as a kind of series, but it was Autofocus Books publisher Michael Wheaton who prompted me to think more conceptually about what I was doing—to think about how the photos were related, and what it might mean to add text and present them as literary nonfiction.

Most of the photos are of houses, and so I began thinking about the people who might be looking back out at this sweaty bearded fellow taking pictures. And of course, it turns out there’s an app for that. I was aware of Nextdoor and the general suburban surveillance state, but I’d until then abstained. I borrowed a neighborhood friend’s account and discovered all the joys and horrors of the app, and I realized these are the people looking out—I’m going to let them speak, in a way, in relation to the photos.

CK: In the Acknowledgments, you mention the paintings of Ericka Sobrack as an inspiration, specifically for helping you “re-vision my residential surroundings.” Are there any particular paintings of hers that especially resonated with you? Which of the photos in the book do you see as most directly influenced by her work?

RR: A long time ago I was in a local café and saw an almost photo-realist painting of a single streetlight illuminating a grassy traffic median, and ever since then I was a fan of Sobrack’s paintings. Many of them are of houses at night. Shadow, light, and subtle details play a primary role in creating what I think of as suburban gothic moods. While much of her work is inspirational, maybe the best examples are clustered in her 2019 paintings: “Beacon,” “Reveal,” “Séance,” “Fortress,” “Threshold.” These are probably why I first stopped to take a photo, because I saw scenes that looked strikingly like her paintings in my own neighborhood. Then I couldn’t stop seeing that way.

You’ll notice there are more day shots than night shots in the book. That was me in part trying to carve out my own space, which (as I eventually realized) was a way of exploring what is gothic and ominous about the daytime. It was important to push against the trope of darkness being negative, scary, a threat.

A couple friends have also pointed out similarities between my photographs and the work of Todd Hido and Gregory Crewdson, who, in addition to Ericka Sobrack, I highly recommend. I’m not a trained visual artist, so there was a lot of anxiety of influence going on! I don’t think I’d have published the photos beyond social media without the addition of the text.

CK: I’d love to hear about your process for arranging the images, for pairing the images with the text, for choosing titles, and for dividing the book into four distinct sections.

RR: The process was really fun most of the time, very intuitive, which is not the norm when I’m writing straight prose. I started by browsing Nextdoor and snagging posts or comments that stood out. After a while I’d search for certain keywords that had thematic relevance and browse those posts. Over time I started piecing together conversations into a massive Word doc.

A lot of the work was free association, especially pairing the images and the text. I’d look at a photo and see what words or ideas it evoked, and if there was an existing conversation that fit, or if I should search Nextdoor for those evoked words, and so on. The process was circular and self-perpetuating in that way. Sometimes a photo-text pairing would help me revise a given text.

I had a lot of material to work with, so I ultimately limited myself to thirty-four total pieces because that’s the number of neighborhoods Orlando was divided into during the period of “urban renewal” that occurred nationwide in the mid-twentieth century, that phrase being code for the destruction and displacement of thriving, primarily Black urban communities. Structurally, I wanted a certain circularity or repetition to happen in places, so the four parts helped spread out some recurring themes and patterns. The photos also, I hope, have a certain kind of movement and resonance within each section, as well as across the book.

CK: Do you know anything about the people who live in any of the homes you photographed?

RR: No. Or at least not yet!

CK: I’m curious to know whether anyone ever stopped you to ask what you were doing. Getting into the spirit of Nextdoor here, I’m guessing that during this process you showed up on a lot of Ring cameras! Did you ever find that your photography was the source of conversation on the app?

RR: No one ever stopped me, and I haven’t seen any posts about an ethnically ambiguous bearded guy in running shorts taking pictures in the neighborhood. This says something about my legibility as White, despite also being Latino, and maybe it also says something about White guilt, because much of this photo-taking period overlapped with the murder of Ahmaud Arbery by racist vigilantes and the June 2020 uprisings. I was more aware than usual of my privileged mobility, while also being nervous about a potential confrontation, especially when I was photographing at night. One thing that’s clear from Nextdoor is that a lot of people are armed and perpetually half-cocked.

But if you’ll indulge a tangent here: There was also something gothic about the Black Lives Matter signs that emerged around this time in my mostly White neighborhood. Eight years before Arbery, almost to the day, Trayvon Martin was murdered by a racist vigilante not far from here. Amid the 2020 protests, though under slightly different circumstances, Salaythis Melvin was shot in the back by James Montiel for running away from Orange County sheriff’s deputies. And just last month in Kissimmee, deputies murdered Jayden Baez for shoplifting. And literally as I type this, Titusville police officer Joshua Payne was charged with manslaughter for murdering James Lowery, who had nothing to do with the alleged crime being pursued. The examples are everywhere and ongoing across the U.S.: Police kill roughly 1,110 people a year and injure thousands more! The racist logic and rhetoric around these killings is not much different than it was a hundred years ago. It’s become cliché to cite Emmett Till. And yet here is history repeating itself over and over.

I felt something terribly uncanny about how suburbanites react to these “reckonings” was present in those yard signs. The conditions in this neighborhood have not changed to make a tragedy of racist boundary policing any less likely. Part of the texture of this historical moment I wanted to capture in the book is a sense of slippery time, time overlayed, time collapsing. I nod to this in the short essay at the end of the book about the relationship between suburbia and colonialism. Suffice to say, when I’m out taking photos, I’m just as wary of “good liberals” in my neighborhood as I am about gun-toting nutjobs. Just as I try to be healthily wary of my own thoughts and actions.

CK: In terms of structure, I’m curious about the choice to end each section with Coyote section titles. We move from “Coyotes (Reason)” to “Coyotes (Solutions)” to “Coyotes (Humans)” to “Coyotes (Encounter).” What were you thinking about with this choice?

RR: The coyote pieces are the most explicit recurring structural element. People post about coyotes a lot on Nextdoorand they’ve really turned the animal into a symbol, a projection of their fears—which left room for me to play, with an obvious nod to the trickster Coyote of Native American storytelling. For these neighbors, the coyote is a problem that won’t go away, and a problem that most don’t fully understand as one of their own making—so for me at least, the recurring coyote pieces signal that this neighborhood is stuck in a kind of gothic White time.

This is related to what I was saying about recurrences in history that feel uncanny precisely because they are forms of Whiteness, which is an identity invested in concealing an understanding of its construction and roots in white supremacy. If there were infinite sections to this book, each would end on a coyote piece, again and again, for eternity.

CK: Do you have a favorite photograph or quotations? Mine, for sure, is on page 25: “We cannot let small dogs be virtual prisoners while letting gangster coyotes run the show.” It so perfectly captures the breathless, infuriated tone of the kinds of messages we encounter on this app, while also conjuring this hilariously cartoonish image of a neighborhood being “run” by “gangster coyotes.”

RR: So much of what people post is almost unbelievably, perfectly absurd. I could imagine some of these lines spoken by characters in Kafka or Joy Williams or Percival Everett or Tom Drury. It’s very hard to choose a favorite, but I think I gravitate to the minute quirks. The woman who says she likes to “sit out in her little area” when talking about her porch. Or “My former neighbor just alarmed me with news of . . .” The use of “alarmed” as a verb is perfect.

Then there are the truth bombs that I’m not convinced the poster always understands the implications of. My favorite among those is: “The police cannot be there to protect you, but they can exact revenge after the crime.”

CK: What’s going to be in the supplemental book content?

RR: This is publisher Michael Wheaton’s bright idea, which is to have a QR code at the end of the book that links to a page that is kept updated with author interviews and other supplemental goodies. I plan to include some photo/text “outtakes” there. This interview. Who knows what else!

CK: You end the book with other resources too, including alternatives to calling the police in your community, information on transformative justice, and a brief history of the land that now makes up suburban Orlando. Why were these important to you to include, and how do you see them contributing to the way a reader will encounter this book?

RR: I think some of these pieces can be easy to consume and laugh at. The book can be read and enjoyed uncritically, or even cynically, as in “I’m in on the joke and look how dumb all these Nextdoor people are!” So I felt the Orlando history and resources from transformharm.org were an important acknowledgement of how the city’s (and country’s) white supremacist origins are directly related to where we find ourselves now. There is an extremely unfunny reality behind many of these pieces, particularly some folks’ constant calls for police intervention.

As Aimé Césaire (who I quote in the epigraph) points out about colonialism, we are all being harmed by racist systems. I wanted to present readers with our innate complicity in the systems that are the legacy of colonialism, but also begin to imagine ways out of them. Many people have been doing this work for decades, so in addition to the above link, I’d point people to the work of Angela Davis, Ruth Wilson Gilmore, and Mariame Kaba, to name only a few.

Click here to purchase this book at your local independent bookstore:

Rain Taxi Online Edition Winter 2022 | © Rain Taxi, Inc. 2022