presented by Rain Taxi and Mizna

Wednesday, May 17, 2023, 7:00pm

East Side Freedom Library

1105 Greenbrier Street, Saint Paul

Free and open to the public! Books will be available for purchase.

Please note this is an in-person event only; virtual attendance is not available.

East Side Freedom Library requires masks to be worn in their building.

Two boundary-pushing Minnesota orgs, Rain Taxi and Mizna, are proud to team up to present an evening with renowned Palestinian writer and human rights activist Raja Shehadeh, who will discuss his new book We Could Have Been Friends, My Father and I. At this special event, the author will be in conversation with Joseph Farag, professor of Asian & Middle Eastern Studies at the University of Minnesota who specializes in Palestinian Literature and Culture. We hope to see you there!

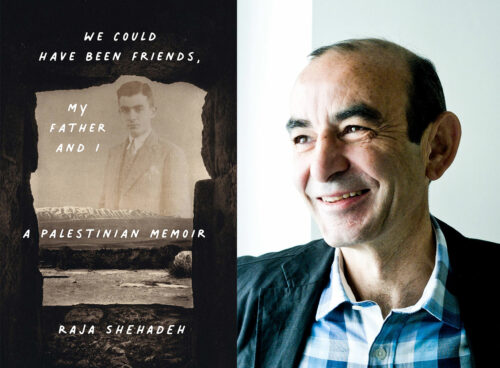

About the Book

We Could Have Been Friends, My Father and I is in part the story of Palestine’s ongoing fight against multiple foreign powers, but it also presents a poignant unraveling of a complex father-son relationship. Set against the backdrop of continuing political unrest, Raja Shehadeh describes his failure as a young man to recognize his father’s courage as an activist fighting for Palestinian sovereignty and his father’s inability to appreciate Raja’s own efforts in campaigning for Palestinian human rights. Then in 1985, Aziz Shehadeh is murdered, and Raja undergoes a profound and irrevocable change.

About the Author

Raja Shehadeh, winner of the prestigious Orwell Prize for his book Palestinian Walks: Notes on a Vanishing Landscape, is widely regarded as Palestine’s leading writer. He is also a lawyer and the founder of the pioneering Palestinian human rights organization Al-Haq. In addition to this new work and Palestinian Walks, Shehadeh is the author of many acclaimed books, including Strangers in the House, Occupation Diaries, Where the Line Is Drawn, and Going Home, which won the Moore Prize in 2020. He has also written for The New Yorker, The New York Times, and Granta, among many other periodicals. Shehadeh lives in Ramallah in Palestine.

About the Moderator

Joseph R. Farag is Assistant Professor of Modern Arab Studies at the University of Minnesota–Twin Cities where his teaching and scholarship focus on the intersection of politics and modern Arab literary production. His first book, titled Politics and Palestinian Literature in Exile (2017), addresses Palestinian short fiction in the wake of the Nakba of 1948; his current book project explores narratives of imprisonment and confinement in novels and memoirs from across the Arab world. Farag's scholarship has appeared in the Journal of Arabic Literature and Middle East Literatures.