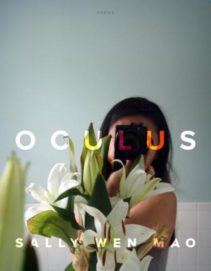

Sally Wen Mao

Graywolf Press ($16)

It’s one thing to discuss the implications of the gaze in a strictly academic style; it is another to force the reader to recognize their complicit role in the act of looking by centering the voice of the one being gazed upon. Sally Wen Mao’s collection Oculus sets out to examine the connections between the gaze and how technology has blurred the definition of sight, making it possible to see without truly seeing. While the speaker in her poems may wonder whether it is possible to break such toxic cycles of prejudice, Mao’s collection has an optimistic underbelly, asking how we can collectively grow and learn.

The question of identity and Western preconceptions of race are the external forces exerted upon the speaker in Oculus, creating the burden of expectation and bias. Mao situates writing at the crossroad of this dilemma in “Occidentalism,” where the speaker expresses worry that

One day,

a girl like me may come across [the tome of hegemony] on a shelf,

pick it up, read about all the ways her bodyis a thing. And I won’t be there to protect

her, to cross the text out and say: go ahead—rewrite this.

The Anna May Wong poems, making up two sections of the collection, discuss this same problem through the historical lens of ongoing failures in cinema. “Anna May Wong Makes Cameos,” chilling in its brevity, conveys the refusal of the dominant, white, patriarchal society to acknowledge the existence of others for more than a brief and convenient moment. In “Anna May Wong Has Breakfast at Tiffany’s,” the speaker laments:

I’ve often pined for them. My progeny. Girls with tar-black

widow’s peaks, who stumble across spotlights in purple tights,taught to be meek. Girls who inherit my warnings, victories,

and failures too.

Creating a hybrid diary-critique in the voice of Anna May Wong, Mao shows the past is not antique or irrelevant, but an ongoing excavation that is always revealing new layers. Mao explores familiar recent works such as Ghost in the Shell and Memoirs of a Geisha, meshing the past and the present in a way that forces the reader to reflect upon the concept of time, to seek out patterns of oppression and injustice. She creates literary and cinematic case-studies that stir up renewed anger as the speaker addresses both the reader and the collective body:

Hacker,

Puppet Master of the laws that govern film—

let this message be clear: I do not comply.

Mao explores the obstacles Western society has placed to prevent people of other cultures from truly belonging—the central issue in Oculus. From the notion of the spectacle as entertainment in “The Toll of the Sea” and “The Mongolian Cow Sour Yogurt Super Voice Girl” to the sense of negligence and passive sight in “Dirge with Cutlery and Furs” and the title poem, Mao’s collection is a sensorial and emotional overload that will disturb the reader in provocative ways.