Edited by Walidah Imarisha and adrienne maree brown

Edited by Walidah Imarisha and adrienne maree brown

AK Press ($18)

by Jane Franklin and Folake Shoga

Walida Imarisha and adrienne maree brown’s AK Press anthology Octavia’s Brood: Science Fiction Stories from Social Justice Movements feels like a distillation of the times—an anthology of dystopias and apocalypses, protest, resistance and revolution. Inspired by the work of the brilliant and innovative Black science fiction writer Octavia Butler, this book seeks to center writers and worlds of color in its visionary fictions.

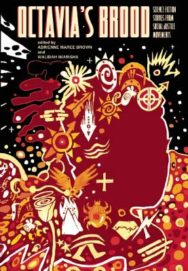

Octavia’s Brood assembles twenty stories, four short essays and a handful of illustrations, bound in a striking cover. Imarisha and brown bring together both well-known and upcoming writers, including a foreword by advisor and collaborator Sherry Renee Thomas (editor of the pathbreaking Dark Matter: 100 Years of Speculative Fiction from the African Diaspora), essays by Tananarive Due and political prisoner Mumia Abu-Jamal, a story from Minneapolis poet and activist Bao Phi, and many others.

Mainstream science fiction has often written out people of color, ordinary people, and the work of liberation struggle, creating futures that are a faster, shiner version of an unequal present. Theorist Mark Fisher uses the concept of “science fiction capital” to convey how predictions of the future work to consolidate power, to exclude, and to coerce—science fiction capital is the power to set the future’s agenda. “We believe it is our right and responsibility to write ourselves into the future,” say Imarisha and brown. Octavia’s Brood strives to put science fiction capital in the hands of the people.

Jane Franklin: These stories are all very immediate—some in the first person, one a television script (the quietly hilarious “Sanford and Sun” in which everyone’s favorite interstellar jazz composer visits a sitcom), and with much emphasis on bodily experience. Some expository passages are a bit longer and rougher than would be ideal, but I found myself intrigued enough by the worlds being built to continue. I was especially excited about these stories as continuations of Octavia Butler’s work—she is such an important figure, but her work is undertheorized and its importance to contemporary SF is often overlooked.

Folake Shoga: I remember one of the first things we discussed is how the stories in the anthology relate to Butler herself. Butler is accurate and scary about power relations to do with race and gender in a way that’s not really mitigated by optimism (unlike for example, Margaret Atwood at the end of The Handmaids Tale), or by sentimentality, or by a conviction that moral right will guide you through a rational universe. Instead she looks at the human condition in a way which, for a change, recognizes the unnumbered lives of the majority, freighted with loss, waste, and pain, ending with no meaning and no progress and no lessons learned. To have achieved what Octavia Butler did, with the difficulties she faced—systemic racism, mental health issues, crippling shyness, and inability to conform to gendered and to genre expectations—and to have been an absolutely original writer and thinker, is truly inspirational. I think a community of sympathetic minds has formed around her writing, found her and each other, and do see her as a role model. It's not about the pessimism. It's about permission to be in your own imaginative space. Letting your imagination go where it naturally would, not where dominant Western literary culture would usually send it. This is the very real way those writers see themselves as “Octavia's Brood,” engendered by her.

JF: And yet both Butler and Octavia’s Brood have this funny kind of optimism—stories like Bao Phi’s “Revolution Shuffle” and Autumn Brown’s “In Spite of Darkness” are set against backgrounds of racism and genocide, but the focus is on the characters’ relationships to each other and to liberation struggle. Lately I’ve been thinking about how this contrasts with dystopian and apocalyptic work by writers like John Brunner and Margaret Atwood which is very despairing and emphasizes total social collapse. I find myself wondering if this is because writers of color and writers who are engaged in liberation struggle see that the apocalypse is already here, already happening to marginalized people, and so they’re able to recognize how people survive and transform under these conditions of extreme stress.

FS: I can't say that I find Butler's work optimistic; in fact I find it grueling to read because the horrible things that happen are so personally wounding to the characters and also so very likely given the established context. Exquisitely expressive and filled with poetic logic, yes—these things are characteristic of Butler and make the stories bearable. But she is bleak. I did find the stories in Octavia’s Brood much more generally hopeful even though many of them take place in blighted apocalyptic landscapes. That's apocalyptic, not post-apocalyptic: any reader of color with the least bit of political consciousness will recognize some of the more over the top details are referring to real things in the contemporary world (okay, maybe not Black people being kidnapped to supply skin grafts to White skin cancer patients). The Black child penalized for cheating after scoring highly on a test, the prisoners fined to pay for their own upkeep: instances of oppression that are not purely fictional. Speaking in April 2015 to the Portland Mercury, Imarisha said, "When we talk about horror stories, living as black folks is a horror story. Michael Brown is a horror story . . . It's a horror story that happens almost every day in the United States, in the black community. So for us, we don't have to imagine horror. We live it every day."

The editors state the purpose of the anthology is “social change and societal transformation” and adrienne maree brown also writes that creatives “can either reflect the society we are part of or transform it.” This has been a guideline to develop the set of practices and workshop methodology from which the anthology grew. It has worked to provide a different common ground in which the stories could root themselves, countering the deafening conventions of Western literary culture in which minorities are hardly even legitimate protagonists. It has given the writers space to breathe and imagine fresh worlds, running on a different logic. The effect has to be cumulative: as more voices are nurtured, they join a larger chorus. The hope has to be that these writers develop and find peers, publishers, and audience, adding to a growing literary culture whose roots lie in the 19th Century, greatly enhanced later by the notion of Afrofuturism. With the growing security of that culture comes the confidence to inhabit the imagination fully, undistracted by disempowering influences.

JF: The book is more than a collection of stories—it’s a matrix for growing a social community, and it’s a place where social justice activists can see themselves and their experiences reflected. As such, it is difficult for me to choose favorite stories from Octavia’s Brood. I like adrienne maree brown’s Detroit fable “the river” for its lyricism, strong sense of place, and ambiguity. An excerpt from Terry Bisson’s 1980s novella of an alternate, radical Civil War, Fire On The Mountain, links these contemporary SF stories to earlier work. Kalamu Ya Salaam’s “Manhunters” made me long for an entire novel and seemed extremely Butler-like in structure.

Alixa Garcia’s “In Spite of Darkness” has really stayed with me, partly because of its illustrations and in spite of its occasional awkwardness. In it, the survivors of a series of genocidal attacks try to preserve the last of their young, hoping against hope for the return of the Sol-gatherers who bring light to their remote and dark planet. On first reading, it seemed slightly heavy-handed, but I found myself thinking again and again of the story’s firelit and dying world and the struggle which blossoms there, and of what it might be to live through the genocide of a people.

FS: The stories reflecting Black diasporic cultural trends resonated with me the most, because I find that little spark of recognition heartwarming. (I find it heartwarming when I get it from Butler too.) The Swahili names in “Manhunters”: Family, Faith, Art, Spirit (Ujamaa, Imani, Kuumba, Nia) recall for me not just an ideal African past of ancient trade routes and cattle droves across the high savannah, but also consciousness-raising groups and Saturday schools and painstaking work around recovery and self- image by dedicated lay people.

I really liked “The River.” It's constructed with craft and precision, using non-hierarchical language to reference a long tradition of vernacular speech. The writing honors the orality of Black diasporic culture in an extraordinarily literary way, producing a clash of sensibilities and a great deal of tension. Formality and abandon are in play, with reticence set against one devastating statement. The abiding emotion is caution but another thing I like about this story is the rage it also expresses, which, like the rage in Walidah Imarisha's “Black Angel,” is entirely appropriate.

JF: “In Spite of Darkness” is characteristic of how this book works, almost requiring a new kind of reading. If you go into this book expecting conventionally plotted stories written in a consistent, conventional science fiction voice that will reward a quick, plot-driven read, you won't find what's best in it. If you go to the book with the desire to engage with the worlds they depict, you’ll find them very rewarding.

FS: The anthology has a second function as a marvelous introduction to contemporary activism around issues of violence, disability, literacy, and participation. I challenge anyone to go through the bios listed in the book and not be overwhelmed by the sheer hard work, creativity, and ethical seriousness of these writers. As a non-USAian, I find it important to overtly and explicitly include Mumia Abu Jamal in that assessment.