by Paula Bomer

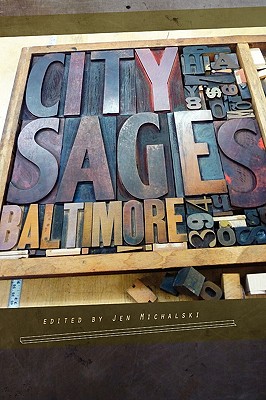

Jen Michalski is the author of the short story collection Close Encounters (So New Media Press, 2007) and the editor of City Sages: Baltimore (CityLit Press, 2010). In 2010 her novella May/September won Press 53’s award for best novella and was subsequently published in Press 53 Open Awards Anthology 2010 ($16). The story of a very young woman and a distinctly elderly woman embarking on an unexpected love affair, May/September is emotionally touching, but it’s not without edge. Straightforwardly written yet with beautiful attention to language, this is a work that is truly radical rather than clever or sensational. In the following interview, Jen was kind enough to talk to me about May/September and discusses what constitutes pushing boundaries in subject matter in 2010, among other things.

Paula Bomer: When you started May/September, were you planning on writing a novella?

Jen Michalksi: This is actually the second novella I’ve written in two years. They don’t start out as novellas, but I guess I have this preconceived notion of novels being long and complicated, and the novellas I‘ve written are just very long stories. I have to wonder, though, because I’ve been involved with the small presses for so long, which publish so many chapbooks, whether the shorter form just evolved from that exposure (and their expectations). I do feel more comfortable writing a novella than a novel. I hope, in the age of Twitter, it catches on.

PB: When one thinks of a May/September romance, one generally thinks of an older man and a younger woman. An older woman and a younger man even seems shocking. But you take it one step further in presenting the relationship between a quite old woman and a woman in her twenties. Were you aware when writing it how far you were pushing the boundaries of conventional subject matter?

JM: I was more aware of the ageism part of it, the Harold and Maude, than the lesbian part. I should add the disclaimer that this story came to me as a fully formed dream, and I woke up and struggled with whether to actually write it. Even though you don’t write for anyone but yourself, you don’t want to waste months or a year on a story that you’re just going to put in a drawer. It wasn’t something that I thought anyone was interested in reading, and yet the dream really affected me and intrigued me. When the “voice” of the story came to me, I sat down and wrote it over the course of a few months. But even then I didn’t know what to do with it. It was a sincere story, but I struggled with the idea of people responding to some sort of “shock” value associated with it. But the response hasn’t been like that at all—people who have read it have responded to it in the gentle, sincere way that I wrote it.

PB: Alice, the young woman who has been hired by Sandra to help her blog/write about her life, is openly gay, and I love the way this doesn’t shock Sandra, whose sexual identity is less defined. Even though she grew up in a time when being gay wasn’t openly accepted, Sandra understands that things have changed. She isn’t bitter, but she’s contemplative. The backbone of this novella is Sandra, at the twilight of her life, looking back—sometimes calmly, sometimes with intense emotion. What inspired that? Did that sort of structure come organically?

JM: The novella for me really is Sandra; I wanted to tell her story honestly, with anger and fear and longing. She says to Alice early in the novella that no one writes about old people, that “no one cares about us.” But she is all of us. The structure came about for me to be an impartial observer, to be entirely in these women’s heads, with the flashbacks mingled with present-tense conversations, even mingled with each other’s thoughts. I wanted the reader to become part of their narrative.

PB: Irony can be—and in the case of this novella, really is—a subtle tool, a way to show how life often doesn’t work out how we intend it to. Sandra’s daughter wanted Sandra to write about her life, but when she finds out Alice and her mother are sexually involved, she’s angry and worried and hurt. Sandra, though likable, isn’t very appreciative of her daughter and it struck me that the elderly rarely are of their children. It’s just so hard to grow old and need help, it’s lonely and frightening. Is Alice sort of a final gift to Sandra?

JM: Sandra and her daughter have never been close, and it’s a concern for both of them, in a way, because Sandra is slated to spend her older, vulnerable years with her. And so Alice is a gift to Sandra in that she shows her that she can be vulnerable, that she can love, but it’s a slap in the face to Sandra’s daughter, who wonders where this Sandra was all her life. But she’s always been there—neither of them wanted to find her. But I hope that the reader is hopeful for mother and daughter in the end.

I think both the young and the old tend to underappreciate the other. Neither thinks the other understands their unique challenges, but we all sort of go through the same things. It was sort of a challenge to me, coming from a close-knit family, to write about a mother and daughter who aren’t close, and to write it from the mother’s point of view. But I understand their fear and pride in not extending the olive branch. I’ve seen so many broken families operate on this principle. And I feel so sad for them. It was hard to write Sandra and her daughter without wanting to make them kiss and make up at some point, but they never do.

PB: Let’s talk about Alice a little bit. The way you structure the novel, in the third person omniscient, we get to see what she’s thinking about as well. Her feelings are protective of Sandra, but genuinely loving. She also seems a little tentative though, and overwhelmed by the distance between them. When writing from her point of view, how complicated did you want to make her feelings for Sandra? Do you feel these emotions are largely because of the age difference or just because people are complicated?

JM: I think Alice may have welcomed the diversion a little since she’s clearly mourning the loss of her girlfriend in the beginning, but the realization that she cares for Sandra is shocking, and the fleetingness of it hits her even harder because she will be the one watching her lover disintegrate. She will be the one left behind. She‘s already lost her father at a young age, and she knows how devastating it was for her. But, to her credit, she decides to pursue the relationship anyway. And she is hurt in the end, but not in the way she expected.

PB: In May/September, there are few to none of the power structures (sexual, social, economic) usually seen in such romances. Alice does get paid by Sandra and taken to a concert, but it's not the tie that binds. Were you intentionally avoiding talking explicitly about these structures?

JM: I didn't think about it as much as one might for a more typical relationship, I have to say. I felt like, when creating Sandra and Alice, I viewed their power struggle in terms of their deficiencies. Instead of people who wind up exerting power over each other (Sandra because she is rich, and Alice because she is young and beautiful), they are broken people who wind up completing the other in unique ways. I also think, that because neither come into the arrangement expecting the relationship to happen, their guard is down a little in that aspect. The real problems for them occur when they try to visualize themselves together in space, and all sorts of problems happen—the uneasiness at brunch, the problem of access at the hospital, perceptions of Alice's coworkers and ex-girlfriend and Sandra's daughter.

PB: When I think of lesbianism in literature, writers like Jeanette Winterson, Djuna Barnes, and Alice Walker come to mind. I wonder if they employed experimental or modernist techniques because the radicalism of their subject matter made it hard for them to write straightforwardly about gay women. In that regard, is the fact that your novella is written in a more conventional narrative form in some ways an advance for gay writing?

JM: I felt that I wanted the story as bare and straightforward as possible, even with the stream-of-consciousness parts. I’m so glad you’re more of a comparative lit person than I—I don’t usually think about which writers I am responding to as a writer, although I did think for when I began that the voice had a very Mrs. Dalloway feel to it, maybe because it’s a similar story. And another writer, Tara Laskowski, compared May/September to Woolf and to Alice Munro, who is very contemporary. I guess I don’t agree with your premise because I don’t view it as a “gay” story—I think of it as a love story. I also think about it as a life story; what happens when someone stops living and then starts again? I think of it as a story about regrets but also risks.

Click here to purchase 2010 Press 53 Open Awards Anthology at your local independent bookstore

Click here to purchase City Sages: Baltimore at your local independent bookstore

Rain Taxi Online Edition, Summer 2011 | © Rain Taxi, Inc. 2011