Peter Richardson

Peter Richardson

St. Martin’s Press ($26.99)

by Ryder W. Miller

The Grateful Dead seem to be calling it quits again, having announced that their last show will be this summer in San Jose following three concerts in Chicago at Soldier’s Field—the last place they played with frontman Jerry Garcia, who died in 1995. They will be bringing it back home to the Bay Area where it all started, and where most of the band members have their roots. This year happens to also be the 50th Anniversary of the band, and it is unlikely that anybody who has seen them live will ever forget them. They have created a fandom that is unmatchable, and they are now old rockers who didn’t burn out or fade away—they still pursue creative ideas and ideals.

Gone, however, is Garcia, who was central to the creative output of the band. There was a time when there was something akin to a religious fervor about this man, who had lost a finger but could still strum a guitar like a genius. Like Bob Dylan, he declined the position of authority and just wanted to play music. The psychedelic experience for some, though, was more than entertainment: it could also be transcendental for those willing to take the risk. The partying was not for everybody, though, and the Grateful Dead could be fun and profound even without altered states of mind. They were also improvisational, so one did not know exactly what to expect from each show—some say they never played a song the same way twice. There have also been new band members over the years that brought new energy and creative ideas with them.

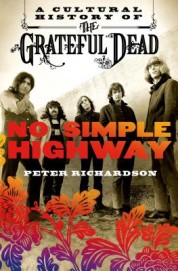

No Simple Highway: A Cultural History of the Grateful Dead from San Francisco State University scholar Peter Richardson is one of at least three books about the band published this year. (Other books include So Many Roads: The Life and Times of the Grateful Dead by Rolling Stone writer David Brown, and Deal: My Three Decades of Drumming, Dreams, and Drugs with the Grateful Dead by Bill Kreutzmann, which is a personal firsthand account.) No Simple Highway gives a broader cultural history of The Dead, who were influenced by many of the famous icons of the 1960s and were bohemians before the term “hippie” was widely accepted. There are many famous people in this tale about who and what inspired the band members. Although they lasted well beyond the 1960s, for many they were representatives of that time, a way to remember that cultural forces that brought an end to the Vietnam War and created new art forms and styles.

Richardson’s book explores the key elements of The Dead’s enduring appeal, including ecstasy (transcendence), mobility (nomadism), and community (tribalism and utopianism). One could find these things by going on tour with the band. As Richardson shows, going to a Dead concert was more than just an evening out—for many it was religious. (Bassist Phil Less called it “A pretty far out church.”) The show could be a place to disappear into a different world and return the next day a little wiser. Richardson explains:

Like most forms of shamanism, the Dead’s version emphasized four broad themes: The universe’s interconnectedness, altered states of consciousness, sharing those experiences through ritual and symbolism, and employing the insights gained after returning to ordinary consciousness.

Like most rock & roll narratives, the story of The Grateful Dead also has its tragic parts, but most of the members have survived to see Richardson’s assessment, which also offers a great deal of information about the time and place in which the Dead began. The book can be slow going in parts, but it is an astute exploration of what has survived from the 1960s and why. The Dead would argue that they are not solely a 1960s band, having continually adapted to the times—a high point being their reaction to Ronald Reagan in the 1980s. They needed to be on their toes to survive in a complicated world. As a group they took on that challenge, and Richardson shows how they fit into the bigger American picture.