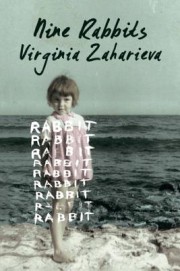

Virginia Zaharieva

Virginia Zaharieva

translated by Angela Rodel

Black Balloon Publishing ($16)

by Chris Beal

Virginia Zaharieva’s Nine Rabbits, translated from Bulgarian, gives English-speaking readers a chance to sample literature from a part of the world about which most of us know little. Straddling the lines between literary genres, the book is classified as fiction, reads like memoir, and at the same time is chock full of recipes suitable for a book on home cooking.

The narrator, while bearing the fictional name “Manda,” seems but a thin disguise for the author. There is no defined fictional persona here; instead, the narrator doesn't seem to know who she is, and hopes to find out by writing. Thus, Nine Rabbits reads more like a memoir than a novel or series of stories.

Each chapter—usually just two to four pages and often ending with a recipe or two—centers around a theme, which might be abstract, concrete, or metaphorical. Examples are “Corset,” “Turkey,” “Exodus,” “Nobody,” “The Mad Hatter.” Usually some event has generated an idea, which is then teased open. The recipes—an eclectic mix of mostly East European dishes with natural, fresh ingredients—sound delicious, and they may also have the purpose of grounding the writer and the writing. It is as though she were saying that we need our connection to the physical world, and food best serves that purpose.

The story is told in two parts; the first explores Manda's childhood while the second records her adult thoughts and feelings. In the childhood section, no adjectives are spared in describing the cruelty of the grandmother who raised her. When things get really bad, Manda seeks solace and help from the nuns at a nearby monastery. Sometimes one or the other of her parents, whose work lives make it impossible to keep her with them, makes a rare appearance:

“My dearest, sweetest little girl,” my mother whispered. “What has my crazy mother done to you? Does it hurt?”

I snuggled up to her. My whole body shook with sobs. I begged her not to leave me with Nikula, to take me with her. But she couldn't. . . .”

If Zaharieva actually suffered abuse to the extent portrayed—and the description of it certainly rings true—she has transcended whatever temptation to ax-grind she may have had: while not excusing Manda's grandmother, she seeks to understand her. This is powerful, controlled writing.

As Part Two opens, years have passed and the narrator has become an adult with an abusive husband; she divorces him with much difficulty, taking her son and eventually making a life with a much younger lover, Christos. A selection from the chapter “Diary” gives a sense of the tone:

I am afraid of life. Writing helps me bear it. I open up space. I pour out onto the pages, so as to free up a place. As I write, I forget living, I watch it from the outside, giving the slowest part of myself a chance to catch up with me. Some people call it soul.

Eventually, Manda becomes a prominent writer in Bulgaria. Still, she feels like a failure, so she studies psychoanalysis and body work. In fact, she explores nearly every avenue for self-discovery open to a modern person. The last chapter finds her at a Zen retreat.

One of the longest chapters describes a trip to Russia with a writers' organization. Manda feels so claustrophobic that she becomes ill as all of the repression during the Communist regime in Bulgaria comes back to her. She writes:

My head is spinning from this kaleidoscopic inversion of values. Here they're again telling me what to do and what not to do. With no choice. They drag me around to some monuments in Kaliningrad, plug my mouth with flowers when talk turns to their problems. They simply turn off the translator's microphone at mention of Chechnya. Poverty, destruction, absurdity, and lies. I feel like I'm caught in a trap.

This chapter is probably powerful for Bulgarian and other East European readers, but for Western readers there isn't enough development of the suffering endured under the Soviet regime to understand Manda’s extreme reaction to being in the “homeland” of this repression, now a thing of the past. Manda was a child during the Communist period, and the main act of the Communist government that she describes was to close down the monastery where she, as a small child, had often sought refuge. Yet her reactions in Russia seem to stem from other events, never mentioned.

Unfortunately, Part Two—which comprises more than two-thirds of the book—never gives the reader the sense that Zaharieva has integrated her experience as an adult. A lot of themes are explored, and yet there is nothing firm to grasp here, no defined sense of who Manda is. While writing Nine Rabbits may have been therapeutic for the author, the reader needs more.