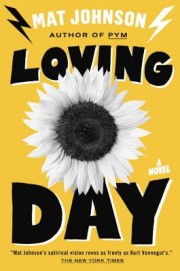

Mat Johnson

Mat Johnson

Spiegel & Grau ($26)

by Elizabeth Tannen

“Race doesn’t exist, but tribes are fucking real.” So declares Warren Duffy, the middle-aged, recently divorced comic-book artist who narrates Mat Johnson’s Loving Day, a novel as richly entertaining as it is smart. Warren, like the author, is mixed-race, born of an Irish father and African-American mother. Also, like the author, he appears mostly white. “I am a racial optical illusion,” Warren tells us. And: “I don’t like feeling white. It makes me feel robbed. Of my heritage. Of my true self. Of my mother.”

So powerfully has this tension driven Warren’s life that it’s led him to Wales, and marriage with a Welsh woman, because surrounding himself with whiteness has reinforced his blackness. When the novel opens, Warren has come home to Philadelphia, where he is grieving not only his failed marriage and comic book store back in Cardiff, but also his father—whose dilapidated Germantown mansion is now his.

Johnson has described this book in an interview as his “coming out as a mulatto,” and above all the novel’s arc chronicles Warren’s slow embrace of his mixed-race identity. He’s spent his life consumed by the fight for admission into the black tribe, of which his light skin marks him as an “asterisked” member. He rejects the concept of biracial, and the notion of a mulatto tribe; in the novel he states, “Mixed people are just a kind of black people anyway.”

Generous use of that antiquated word, mulatto, is one way in which Loving Day subverts our usual framework of discussion around race. Another is its celebration of tribalism itself—a value that is, essentially, un-American. We like to imagine ourselves immune from the needs to belong, to depend. We prefer post-racial mythologies in the same way we prefer post-historical ones: we use the past as ornament, not as identity.

At the center of Loving Day is a pair of love stories: between Warren and the newfound teenage daughter that surfaces soon after his homecoming, and between him and a love interest, Sun, whose physical resemblance to himself is so striking that he observes on sight she could be his twin, and who serves as his foil when it comes to views on race. He and Sun first encounter one another at a comic conference, but she resurfaces as a teacher at Melange, the utopian, militant mixed-race arts and educational center that holds together the novel’s characters and themes.

Johnson has a knack for pulling off the semi-surreal, and Loving Day does a deft straddle between the realistic and the bizarre. He also has a gift for comedy. Some readers might be turned off by Warren, immature and openly sex-crazed, irresponsible and often self-loathing. But others will be charmed by his relentless, self-deprecating humor and brutal, vivid sense of self—as complicated and contradictory as that self might be.