by Roger Gilbert

Illustrated by Ahndraya Parlato

Some poets invite us into their homes. W. B. Yeats’s Thoor Ballylee and Robinson Jeffers’s Tor House figure prominently in their poetry while remaining coldly majestic edifices. Not so Gertrude Stein’s Paris apartment, whose rooms and objects spark the verbal fireworks of “Tender Buttons,” or W. H. Auden’s Kirchstetten cottage, lovingly displayed from bathroom to attic in “Thanksgiving for a Habitat.” James Merrill’s Stonington residence plays an intimate role in his work, especially the flame-colored salon in which the poet and his partner contacted the spirit world. Attentive readers of A.R. Ammons could practically draw a map of his backyard at 606 Hanshaw Road, though they’d be hard pressed to describe the inside of the house. Donald Hall’s Eagle Pond farmhouse is a vivid presence in his poems, helped along by copious prose sketches.

John Ashbery is not exactly that kind of poet. His poems contain little in the way of conventional description. When he does paint scenes, whether interior or exterior, the odds are good that he’s making them up (see “The Instruction Manual”). And yet touring the poet’s magnificent stone and clapboard house in Hudson, New York, one has an eerie sense of déjà-vu. It’s not that any of the objects or artworks on display appears in Ashbery’s poems. Rather, we feel we’re inside the imaginative space from which the poems issue. One might have to go back to Pope’s famous glass-encrusted grotto at Twickenham to find an environment so meticulously crafted to embody a poet’s sensibility. David Kermani has suggested that the house is a kind of “physical poetry. . . a three-dimensional Ashberian milieu,” and one can indeed find many points of contact between that milieu and the richly layered environment Ashbery creates in his poems.1 Above all the house shares the poetry’s ambidextrous spirit, balancing past and present, familiarity and surprise, sophistication and perversity, pathos and humor, all with the same off-handed elegance the poems possess.

Ashbery bought the Hudson house in 1979 but only began living there in the mid-eighties. Its establishment thus coincides with the emergence of what many critics have recognized as the distinctive aesthetic of his later work. Ashbery had always been preoccupied with inner spaces, but before Hudson those spaces often seemed to possess an oppressive sameness. His fullest expression of this claustrophobic mentality comes in “Self-Portrait in a Convex Mirror”:

I feel the carousel starting slowly

And going faster and faster: desk, papers, books,

Photographs of friends, the window and the trees

Merging in one neutral band that surrounds

Me on all sides, everywhere I look.

And I cannot explain the action of leveling,

Why it should all boil down to one

Uniform substance, a magma of interiors. 2

Nothing could be farther from the brilliantly tessellated surfaces of the Hudson house than this dull uniformity. The problem these lines describe is not merely one of poor interior decoration, of course; as Emerson says, “the ruin or the blank, that we see when we look at nature, is in our own eye.”3 A central project of Ashbery’s later poetry has been to train the eye to see and savor the infinite variety of its environment. For Ashbery that environment is predominantly cultural, not natural, a forest of symbols rather than trees. The house in Hudson can be seen as his attempt to create a space where differences are magnified, where things refuse to merge into a neutral band but remain exuberantly distinct.

Photo by Ahndraya Parlato

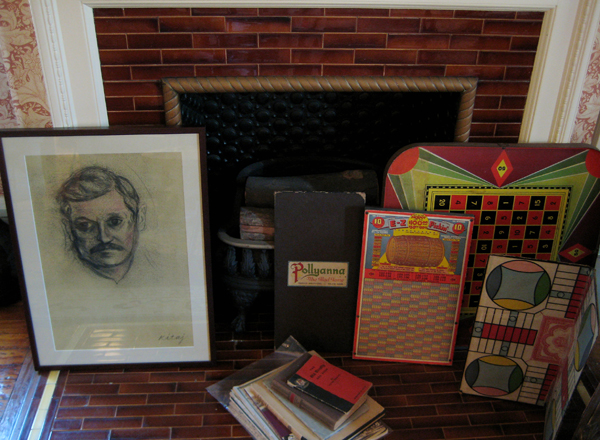

Earlier in “Self-Portrait in a Convex Mirror,” ventriloquizing Parmigianino, Ashbery declares that “the soul has to stay where it is, / Even though restless, hearing raindrops at the pane, / The sighing of autumn leaves thrashed by the wind, / Longing to be free, outside.”4 The soul here sounds suspiciously like a bored child stuck indoors on a rainy day, a condition Ashbery must have experienced often during his youth in Rochester, Sodus, and Pultneyville. Presumably it was during such long afternoons that he resorted to the amusements of comic books, board games, radio serials, and tomes like Three Hundred Things a Bright Boy Can Do, which furnished some memorable passages in “The Skaters.”5 One of Ashbery’s strategies for combating the “action of leveling” in Hudson is to liberally strew the house with reminders of such rainy-day diversions. In “Soonest Mended” Ashbery declared that “probably thinking not to grow up / Is the brightest kind of maturity for us,”6 and this sentiment seems to govern the aesthetic of the Hudson house, at least in places. Like Joseph Cornell, an artist with whom he has some clear affinities, Ashbery treasures old toys, dolls, and other childhood souvenirs. Like Cornell, he also enjoys juxtaposing such tchotchkes with artifacts of high culture and adult refinement. A nice example of this penchant can be found in the dining room china cabinet, whose elegant Willowware plates and cups rub elbows with a ceramic mug adorned with a portrait of Little Orphan Annie—presumably a prize acquired long ago in exchange for Ovaltine seals.

Much has been said about Ashbery’s fondness for conjoining specimens of high and pop culture—Ariosto and Happy Hooligan, Milton and Daffy Duck—and the Hudson house abounds in visual variations on this trope. In part, these reflect Ashbery’s insistence on “not growing up,” but they also stage Jamesian collisions between homespun Americanness and European sophistication. The house itself is a splendid Victorian, lovingly restored and filled with period furniture, wallpaper, and stained glass. Its dark wood-paneled walls and curtained windows create a crepuscular atmosphere that suits Ashbery’s introspective temperament well. Ashbery himself has said more than once that the house possesses “a gloom one knows,”7 and explained that he finds its nineteenth-century ambience comfortingly reminiscent of his grandfather’s house in Rochester.8 Those who regard Ashbery as a quintessentially postmodern poet might be surprised at how thoroughly his surroundings in Hudson evoke bygone eras. In fact, this too is a trait shared by his poetry. Ashbery often speaks of his fondness for nineteenth-century poets like Keats, Hölderlin, Baudelaire, Tennyson, and Whitman, along with ostensibly “minor” figures like John Clare, Thomas Lovell Beddoes, and Edward Lear.9 The extent to which his poetry draws on Romantic idioms and rhetoric in a spirit of homage rather than parody has still not been fully recognized. Yet his commitment to a wide range of avant-garde modes and techniques is undeniable as well, and shows itself throughout the house, most clearly in the many paintings by the likes of De Kooning, Katz, Rivers, and Kitaj that adorn the walls. The result is a heady layering of styles, traditions, and aesthetics, as bright patches of modernism vie for attention with Persian carpets and Chippendale furniture.

Photo by Ahndraya Parlato

At least two large principles of order can be discerned in the house; needless to say, they both inform Ashbery’s poetry as well. One is that of the collection, groupings of objects that visibly belong to the same category. Ashbery parodies his own hunger for “collectibles” in a poem called “Till the Bus Starts”:

And greened copper things

like things out of the thirties.

I must have one—no,

make that a dozen, all wrapped

fresh, at my address.10

Here likeness is the dominant aspect. Among the collections to be found in Hudson are American art pottery in the library, 1920s glassware in the guest bedroom, fish molds in the kitchen, and wax fruit in the dining room (the latter, I’m told, carefully chosen for its signs of imminent decay). If uniformity is a condition to be lamented, one might wonder why Ashbery seems to take such pleasure in gathering similar objects and putting them on display. Some lines from “Scheherezade” may shed light on this question:

But most of all she loved the particles

That transform objects of the same category

Into particular ones, each distinct

Within and apart from its own class.11

Under the right conditions, similarity can become a showcase for difference. Closely seen, things that at first appear interchangeable reveal a numinous specificity. Ashbery’s arrangements of like objects artfully point up subtle contrasts in form, texture, and color. This is the same logic that underlies his penchant for poetic forms like the sestina and the pantoum, in which repeated words and lines undergo minute changes of shade and resonance. Not all wax plums are made alike.

A second organizing principle in the house is that of the rebus. Again an element of nostalgia can be felt in Ashbery’s predilection for the kind of whimsical picture writing once popular in children’s books and magazines. The word “rebus” itself occurs surprisingly often in his poetry, as in these lines from “The Wrong Kind of Insurance”:

All of our lives is a rebus

Of little wooden animals painted shy,

Terrific colors, magnificent and horrible,

Close together. 12

The clustering of disparate objects to “spell” a cryptic sentence is a method hinted at in many of the nonce assemblages that grace the surfaces of cabinets and bookcases, especially in the upstairs rooms. These show a kinship with the work of one of Ashbery’s favorite contemporary artists, Trevor Winkfield, whose paintings are especially well represented in the house. In his introduction to a book of Winkfield’s dazzling acrylics, Ashbery writes:

The colors are those of brand-new but antique toys that have been randomly stacked together: intense pastel greens, banana-yellow, vermilion, chartreuse, Tabasco red, Kool-Aid grape: an assembly whose components ought to “scream at” each other, but which are instead intoning something ineffable, some music of the spheres, though the spheres appear to be rolling around on the floor of a nursery rather than in the heavens.13

This could easily describe many of the enigmatic arrangements to be found in the house, some of which do in fact feature “brand-new but antique toys.” Where the collections take similarity as a ground for the articulation of difference, the rebus-like gatherings use superficial differences of category to hint at deep affinities. Mass-produced toys and exquisitely fashioned objets d’art may at first appear utterly incommensurate, yet when placed in the right configuration they can be made to speak with a single voice. Needless to say, such improbable juxtapositions are everywhere in Ashbery’s poetry too. Here for example are the opening lines of his most recent book, A Worldly Country:

Not the smoothness, not the insane clocks on the square,

the scent of manure in the municipal parterre,

not the fabrics, the sullen mockery of Tweety Bird,

not the fresh troops that needed freshening up.14

What Kenneth Burke calls “perspective by incongruity”15 lies at the heart of Ashbery’s creative temperament, whether manifested in words, objects, or images (he has in recent years become a prolific collagist).

I’ve suggested that the house in Hudson mirrors a significant change in Ashbery’s poetry, beginning in the 1980s. This new style might be characterized as decorative, provided that word is stripped of the unspoken “merely” it usually carries. Where his poems of the sixties and seventies can often seem austere in their dense broodings on time and consciousness, Ashbery’s more recent poetry gives itself over to florid embellishment and exfoliation, taking delight in the endless capacity of language to generate pattern and surprise. In this respect the Hudson house feels like a concrete manifestation of the same energies that so vividly shape Ashbery’s work of the last two decades, as represented in his recent selected volume Notes from the Air. If the collections that Ashbery published from 1956 to 1984 resemble discrete dwellings or way stations, each with its own look and layout, the books that have appeared since are more like rooms in a single opulent mansion, distinct in tone and purpose yet united by a common aesthetic. The restlessness that made the first half of his career feel like a fascinating series of experiments, each turned in a new direction, has given way to a more stable and centered artistry, a kind of poetic nesting. Yet it would be wrong to suggest that Ashbery has settled down completely, even at eighty. He continues to travel weekly between Hudson and Manhattan, where he’s lived in the same Chelsea apartment building for over thirty years. The regular oscillation between these two utterly different milieus seems to be essential to his creative process, brisk infusions of urban energy followed by retreats to the rich artifice of Hudson.17 One might see in this circuit a topographical embodiment of the cycle between imagination and reality, fact and dream, that Ashbery inherits from Wallace Stevens. (Stevens found his version of that topography in his daily walks from home to the Hartford Accident and Indemnity Company and back.) As an artist too, Ashbery is still on the road, still trying new forms, taking new risks. For all of the care and ingenuity he has lavished on his Hudson house, it remains for him a place to venture from, a mooring of starting out.

1“IN CONTEXT: Created Spaces as a New Resource in Ashbery Studies,” LIT 12 (2007), p. 222.

2Self-Portrait in a Convex Mirror (New York: Viking, 1975), p. 71.

3 Essays and Lectures, ed. Joel Porte (New York: Library of America, 1983), p. 47.

4 Self-Portrait in a Convex Mirror, p. 69.

5John Shoptaw, On the Outside Looking Out: John Ashbery’s Poetry (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1994), p. 93.

6The Mooring of Starting Out (New York: Ecco, 1997), p. 232.

7John Ashbery in Conversation with Mark Ford (London: BTL, 2003), p. 64.

8“The Poet’s Hudson River Restoration,” Architectural Digest 51.6 (June 1994), p. 36.

9 See Ashbery’s lectures on Clare and Beddoes in Other Traditions (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2000). He praises Lear in an interview with Michael Glover in The New Statesman (May 23, 2005).

10And the Stars Were Shining (New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 1994), p. 14.

11Self-Portrait in a Convex Mirror, p. 9.

12Houseboat Days (New York: Viking, 1977), p. 49.

13Selected Prose, ed. Eugene Richie (Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 2004), p. 260.

14A Worldly Country (New York: Ecco, 2007), p. 1.

15 Burke first introduced the phrase “perspective by incongruity” in Permanence and Change: An Anatomy of Purpose (New York: New Republic, 1935).

16For a fuller discussion of this “late” style, see my “Ludic Eloquence: On John Ashbery’s Recent Poetry,” Contemporary Literature 48.2 (Summer 2007), pp. 195-226.

17Larissa MacFarquhar discusses the relationship between the Hudson house and the Chelsea apartment in “Present Waking Life; Becoming John Ashbery,” The New Yorker (November 7, 2005), pp. 87-97.