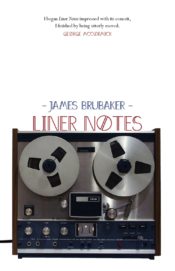

James Brubaker

James Brubaker

Subito Press ($18)

by Alex K. Hughes

James Brubaker’s Liner Notes, a collection of thirteen stories, explores a fascination with music and pop culture. A jazz musician who has lost memory of his musical talents, a museum curator who habitually acquires the wrong historical items, and the renowned Brian Wilson make appearances. To the protagonists, music is more than a hobby; it is the way they understand the world and try to protect themselves from inevitable pain. However, their successes are often only temporary.

In “Four Walls Won’t Hold You,” Derek is caught in the middle of parental disputes and abuse. Torn between acceptance and futile action, he escapes into the world of Michael Jackson’s Thriller, the songs of which parallel his life: “The lyrics are simple and urgent. . . . about being trapped and needing to escape so bad that walls can’t hold him. . . . You don’t understand how a city can wink, or sigh, or have a heartbeat, but you know about the four walls.” And yet the cassette can only last so long, the ribbon can only stretch so far. The story reminds readers that reality always encroaches. This knowledge could be devastating, but music exists beyond the tangible. It can be carried in memory or produced in hums. The destruction of the object can never destroy the positive impact.

The best stories in Liner Notes pair the melancholy with manic energy. Take “Flavor Flav Travels Through Time and Reads About Himself on Wikipedia,” where the titular hype man and reality TV star finds himself unstuck in time. An unlikely Billy Pilgrim, Flavor Flav relives missed opportunities in childhood, untapped musical prowess, and his seventy-fifth birthday—trapped in a nursing home, but loved by his daughter. The story, a prime example of Brubaker’s reality-bending fiction, rises beyond satire and science fiction, even while it balances absurd humor and space captains. The utterly human portrait of Flavor Flav takes center stage, and the easy caricature associated with so many reality TV episodes is ignored.

While having a deep knowledge of obscure music and popular culture may enrich the reading experience, Liner Notes largely succeeds on its own merits: crafted human figures and a spiraling use of dove-tailed language. At the end of “Haunted Resonance: A Memoir”—a hypothetical story wherein Brubaker tries to pick his wife’s eulogy song—he confronts the terror of having “nothing. No wife. No song.” Each sentence builds, twisting the ones before. When the final words run down the page, a crummy pop song becomes a landmark throughout his life, a tune now impossible to hear without the flooding memories of emotional decades. Brubaker’s exploration of the meaning that could be incites us to consider what is arguably the point of a good song or a good story: to feel connected.