Edited by Steven Huff

Edited by Steven Huff

Tiger Bark Press ($16.95)

by Cindra Halm

From the beginning, Bill Knott and his poems survived his life and his death. When a young Midwestern poet calling himself Saint Geraud (1940-1966) (a "virgin and a suicide," as described on the book jacket) came onto the scene in the mid-1960s, the literary community was startled, swept, prodded, even electrified/electrocuted by his stark, capacious voice—one that crafted intense, syllable-conscious, emotional truths of "sleep, death, desire." In an astonished tone, Paul Carroll writes a preemptive homage in his Foreword to The Naomi Poems: Corpse and Beans (Big Table, 1968): "Lyrical poets of this order speak all but exclusively of the business of the heart—its fetishes, obscure needs, nostalgias, angers, rituals, longings for oblivion, masks, miseries, and its splendors . . . This is that lyrical voice which speaks over centuries to all men and women regardless of culture or race or time."

Fast-forward to 2017, to a collection of essays in which both mortal writer and immortal words are parsed, contextualized, puzzled over, and elegized. Bill Knott, the earthly inhabitant of the otherworldly pseudonym, inspired, perplexed, maddened, and blessed those he touched in his seventy-four years as a complex, often acerbic personality; a brilliant, driven, self-deprecating poet; and a nurturing, exacting teacher. Knowing Knott: Essays on an American Poet, edited by Steven Huff, gathers fifteen friends, colleagues, students, writers, editors, publishers, and collectors, after his unexpected death of 2014, to try and make sense of their sometimes uncomfortable, always unconventional, relationships with Knott's dissatisfied body/mind/incarnation and deeply affecting art. What emerges is overarching acceptance and awe, even amid recountings of childhood traumas, social awkwardness, self-sabotaging & self-ostracizing behavior, and unusual generosities. Knott, whose impassioned, often irreverent poems and theater of personas created a loyal following in contemporary literature's post-confessional, Vietnam War-wracked surrealism, was loved by these intimates. The memorials function as spoken eulogies do for any eccentric, often dysfunctional family member: they don't spare difficult truths, but tender them with humor, with the speakers' own foibles, and with ballasting acts of beauty in order to render a full humanity.

One of the most consistent and common anecdotes among the essayists involves the wheres, whens, and hows of encountering Knott's poems for the first time, most often through the aforementioned debut, The Naomi Poems: Corpse and Beans (Big Table, 1968) or the same publisher's The Young American Poets (1969). If you are a Knott fan, you know these crisp lyrics and indelible, startling/stalking image-insights, so it's fun to read how others in the club became initiated. Paul Carroll's early praise and declaration of promise rise again in the voices here as well. One oft-cited, Zen-koan-like poem has traveled not only in the memories of Knott’s admirers but with the poet himself over the arc of his career and life/lives; part of it was placed, by poet and executor Robert Fanning, on his gravestone:

Death

Going to sleep, I cross my hands on my chest.

They will place my hands like this.

It will look as though I am flying into myself.

Stephen Dobyns writes about Knott's famous wit and wrung out, carefully chosen language and affect: "He used puns and especially liked the pun on his name: ‘The way the world is not’ is the first and fourteenth line of a love poem . . . He liked the denial of not, liked the negative; he liked erasure and disappearance; he liked the contradiction of being not. As he wrote in a poem called ‘Poem:’ ‘Nothing has its own niche.’" This collection both honors the poet with his name-punning, and erases the erasure: "Knowing Knott" becomes "No-ing Not," and the double negative transmutes into a resounding and heartwarming affirmation, collectively summoned by his community and proclaimed on the cover for all.

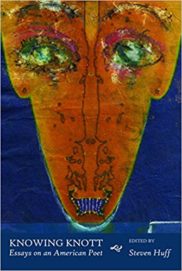

The cover also features one of the poet’s unnamed paintings (a presumed self-portrait?)—a floating, bony face with glittering jewels for eyes that nonetheless drift slightly away from the viewer and seem to indicate the poignancies within both the face and the pages. That the collection gives us this as well as six paintings in the book's center is a gift that includes and extends Knott's imaginative gestures as well as the pathways for knowing them and knowing him.

Necessary and welcome are two women's perspectives. Star Black, long-time student, friend, collaborator (more of Knott's paintings appear in their Saturnalia 2010 poetry/art book, Velleity's Shade) and sometimes live-in partner, offers domestic life and work habit insights with a sense of traveling through various literal and figurative geographies:

Bill was easy-going and content at home when focused on his activities: writing and revising, ordering poems, printing poems, making his own paper or paintings or drawings or artist's books. He kept telling me, when teaching me how to assemble and to bind a hand-made book via Japanese stab-binding, a patterned sewing process using waxed thread, that making anything “is a thousand little details,” and that “tiny faults are part of it.” . . . We both had weird, hobbling flaws. He was, in many ways, more healthy than the distracted emptiness behind my drawn curtains of yin. He had energetic impatience.

Leigh Jajuga, a personal assistant and presumably the last friend to see him alive, writes, "There was a quiet understanding that we were not to discuss poetry together, despite his request for a student in the poetry department for help to organize his books and go to the store. I never questioned it, and in fact, it gave me a great ease to avoid these conversations. I didn't want to constantly feel myself measuring my intellect, going back over the conversations day-by-day, worrying that Bill had doubted my competence." Over time, as trust and friendship developed, Knott encouraged her to self-publish and start a small press, giving her his Mac laptop, refusing any money for it. These quieter reflections counterbalance many more strongly opinionated remarks about his work and career.

John Skoyles: “I miss Bill Knott. I foolishly thought he'd always be around—I think many of us did—because he had always been there to remind us of some folly taking place in the world of literary favor-trading and blatant careerism. Always there to heckle the poetry establishment with high wit and devastating humor."

Timothy Liu: "Bill Knott's genius has/had something to do with subversion, both in the way he wrote his poems and in the way he published them. Rather than play by the rules that were handed down by rote, he changed the game, raging against the dying of some primordial light, his inner orphan unwilling to kowtow to rampant cronyism run amok. He not only put his money where his mouth was, he also bit the hands that fed him, and in many ways, paid a heavy price. Idiot-savant outlier and/or cautionary tale for recent MFA grads? In my own incredulous eyes, he was a Trickster/Maverick sine qua non the likes of which I'd never seen before and haven't seen since."

Acquaintances will grieve and marvel alongside these faceted voices of anecdote. Aficionados of his work will sink more deeply into the man of masks behind the piercing images and ideas. Curious students of poetry will meet a deeply wounded human whose profound talents and inner convictions and compulsions carried him, ever lonely but reaching, battling the edges of private and public, into the literary canon.