Lindsay Blair

Lindsay Blair

Reaktion Books ($24)

by Randall Heath

In the end the dangerous pleasures of the private world is, for those who can afford it, the only panacaea.

—Alan Pryce-Jones, “The Private Worlds of Youth”

Joseph Cornell lived deeply inside a world of his own making—a world of melodious atmospheres, charmed static universes, and midnight rendezvous in long-forgotten hotels. His work is animated with both a childlike sense of wonder and a profound sense of the interconnectedness of things. Lindsay Blair's fascinating and sensitive new study, Joseph Cornell's Vision of Spiritual Order, seeks out the method behind the man and opens the door into the secret realm of his art, offering a startling glimpse into the mind and process of one of the 20th century's most fascinating and original artists.

Cornell was a legendary wanderer. While his travels rarely took him beyond the confines of New York City, his compulsive habit of collecting ephemeral objects, memories, and images allowed him to visit places few people will ever see. Yet at times his impulses threatened to overwhelm him. The desire to control and manage the flood of impressions and objects led to his creation of files or "dossiers"—collections of found photographic images and impulsively scribbled notes arranged around particular themes. By analyzing the construction and content of these dossiers, Blair offers a cogent and revealing look into the basis of Cornell's art.

Blair takes as her starting point a dossier entitled "GC 44," begun in the summer of 1944 while Cornell was working at a nearby garden center. Cornell's obsessively reflective state of mind is revealed through "The Floral Still-Life" section of the dossier, which focuses on a specific experience he had: while riding his bicycle in rural Flushing, Cornell was passed by a truck bearing the logo of a meat and fish company. The convergence of the rural setting, the seemingly mundane logo, and his particular state of mind, created for Cornell a moment of poetic reverie or, as he calls it, a "metamorphosis of the sign into the more poetical." For Cornell, such moments took on mystical proportions, and more than 20 years later he was still musing on the experience and attempting to come to a fuller understanding of its significance. While the material in this dossier was never actually converted into a single work of art, Blair effectively shows how it offers crucial insight into Cornell's working method. Known for his frequent rambles through the thrift shops and dime stores of New York City, and for his voyeuristic crowd-gazing in such places as Grand Central Station, Cornell is revealed to be a "seeker of visions," a man in search of the state of mind that produces a momentary transformation of the mundane into the extraordinary. It was in the recollection of these events that Cornell found himself in touch with the creative impetus that led to the construction of his boxes.

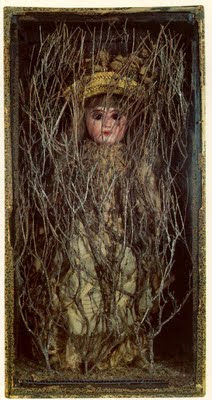

Untitled (Bebe Marie) early 1940s

Robert Motherwell's criticism of Cornell—that he was, in Blair's words, "attempting to fashion art from the stuff from his grandmother's attic"—is a statement that while intended to dismiss, in fact gets at the heart of Cornell's inspiration. Nostalgia is an ever-present sentiment in Cornell, one he unapologetically embraced for the associations with childhood that it created. As Blair writes in the most fascinating chapter of the book, "Origins of Selfhood," Cornell's embracing of the past was an attempt to recover an idyllic state of mind, one associated with the mind of the child: "Certainly, he wanted to see as a child, but then to advance and ally this vision to the sensibility of the artist and the skills of the craftsman." And yet as Blair's discussion of Bébé Marie—a large box containing a Victorian doll encased behind a wall of tree branches—indicates, Cornell's far reaching mind was also fraught with a paradoxical sense of confinement:

The idea of physical imprisonment setting free the creative imagination obsessed Cornell because this was the image he had of his own personal situation. Running like a refrain throughout his dossiers and diaries are comments about being in the cellar at Utopia Parkway confined by his domestic responsibility, and further confined by the chosen form of his boxed art. And yet, the situation seems to have encouraged him to find freedom in his art.

The idea of an artist creating from a place of restriction seems particularly radical given the modernist insistence on throwing off all restraint, be it moral, sexual, or traditional. Yet it is just one of the ways in which Cornell parts company with his contemporaries. His refusal to engage in the kind of disturbing and irrational indulgences associated with the Surrealists, with whom he is often linked, distances him from that group and places him completely in his own category. Not that his art isn't infused with an air of voyeurism, fetishism, and sexual repression, it's just that these forces remain forever suspended below the surface, creating a sublimated tension that fascinates as it enchants. Cornell was content to be repressed, to forever wander in his private world, finding there the understanding he needed to evoke what he called his "white magic."

Joseph Cornell was a true original who by using the artist's most profound gift—the ability to transform the surrounding world—created timeless works of provocative beauty. And with Joseph Cornell's Vision of Spiritual Order, Lindsay Blair has led us one step closer to a fuller understanding of this famously enigmatic yet essential figure.

Click here to purchase this book at your local independent bookstore

Rain Taxi Print Edition, Vol. 3 No. 3, Fall (#11) | © Rain Taxi, Inc. 1998