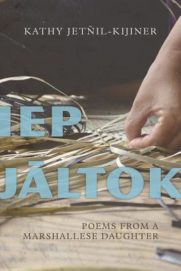

Kathy Jetn̄il-Kijiner

Kathy Jetn̄il-Kijiner

University of Arizona Press ($14.95)

by John Bradley

Two concrete poems entitled “Basket” open and close this engaging book. The arrangement of the words of each poem form the curved outline of a basket, which connects the reader to the book’s title. “Iep Jāltok,” we learn from the Marshallese English Dictionary, means “A basket whose opening is facing the speaker.” It also refers to a female Marshallese and to their matrilineal society.

Some may remember images of the Marshall Islanders from the era of nuclear “testing,” the euphemism employed by the U.S. for the explosions of nuclear bombs in the Pacific from 1946 to 1962. Jetn̄il-Kijiner evokes this period in “History Project,” a poem that narrates her attempt at age fifteen to confront the past:

I flip through snapshots

of american marines and nurses branded

white with bloated grins sucking

beers and tossing beach balls along

our shores

and my islander ancestors, cross-legged

before a general listening

to his fairy tale

about how it’s

for the good of mankind

Her use of lowercase for “American” indicates both a fifteen-year-old’s writing style and also the anger of those whose home was made into a nuclear bomb testing site.

“History Project” includes statistics on the death of the Marshallese from cancer due to radioactivity from the bombs. Ancient history, some may say. Surely we all know the consequences of nuclear testing in the Pacific and how those who were its victims feel about it. And yet when “three balding white judges” evaluate her history project, they somehow believe her project embraces the “fairy tale” told by the Americans. One judge says: “Yea . . . / but it wasn’t really / for the good of mankind, though / was it?” She abruptly concludes her poem: “and I lost.”

Jetn̄il-Kijiner’s losses include the death of her niece Bianca from cancer, as she relates in “Fishbone Hair.” The poem moves, in eight parts, from the discovery of two “ziplocks” of Bianca’s “rootless hair / that hair without a home” to a mythic conclusion in which Bianca’s “fishbone hair” becomes a net, echoing a Chamorro legend. In this legend, women used their hair to weave a net and preserve their islands from a “monster fish.” Over and over in the book, Jetn̄il-Kijiner weaves a net of language to heal and protect. Yes, there is an occasional cliché—“red as tomatoes”—but they are rare, and the language pulses with emotive depth.

Loss once again threatens the Marshall Islands with a terrifying future which Jetn̄il-Kijiner bravely faces: global warming. This means rising seas and the flooding of the Marshall Islands. She promises her daughter, in “Dear Matafele Peinam,” that “no one’s drowning, baby // no one’s moving / no one’s losing / their homeland.” We see this promise tested in “There’s a Journalist Here,” which describes the damage done to an island home by the rising ocean. Still, the author does not surrender. In “Two Degrees,” she tells us she knows that “if humans warm the world / more than 2 degrees” it will flood her home. She’s told at a conference on climate change how two degrees is “just a benchmark for negotiations.” Once again, we see how quickly the world forgets the Pacific Islanders, even those knowledgeable about climate change. The closing of “Two Degrees” suggests how to move the discussion beyond the comfortable abstraction of numbers:

remember

that beyond

the discussions

numbers

and statistics

there are faces

all the way out here

there is

a toddler

stomping squeaky

yellow light up shoes

across the edge of a reefnot yet

under water

Iep Jāltok reveals a poet who—in her first book—has already found her voice, who draws her poetic power from her islands, her culture, and her people’s history. Sometimes utilizing folklore or mythology and other times stream-of-consciousness, her poems change shape and strategy. However, they consistently demonstrate a clear focus. Whether sharing the folk beliefs of the islanders, or witnessing the terrible cost of cancer from nuclear testing, or recalling her own experiences as a mother, her poems educate and advocate on behalf of the Marshallese. At the same time, they speak for everyone, as climate chaos is not limited to islands in the Pacific. We are fortunate to have a poet confront a global issue with both craft and courage: “Maybe I’m / writing the tide towards / an equilibrium / willing the world / to find its balance.”