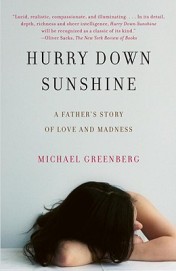

A Father’s Story of Love and Madness

A Father’s Story of Love and Madness

Michael Greenberg

Other Press ($22)

Vintage ($15.95)

by Jacob Appel

In an impatient era of loglines and blurbs, a memoir like Michael Greenberg’s Hurry Down Sunshine risks being pigeonholed as a narrative of mental illness. Such a response is unsurprising for a work that begins with the author declaring that on July 5, 1996, his fifteen-year-old daughter, Sally, “was struck mad” and then follows father and child through the ordeal of her hospitalization, outpatient therapy, and sedation with soul-effacing antipsychotics. So one can understand why neurologist Oliver Sacks, writing in The New York Review of Books, recently compared the volume to two other highly-regarded personal reflections on bipolar disorder, John Custance’s Wisdom, Madness and Folly: The Philosophy of a Lunatic (1952) and Kay Redfield Jamison’s An Unquiet Mind (1995). Yet while madness may be the warp that binds together the tapestry of Greenberg’s story, his bracingly forthright and intensely unsettling tour de force is no more a mere tale of insanity than is King Lear. Instead, Greenberg sieves the events surrounding his daughter’s “crack-up” to distill an eloquent disquisition on the fragility of daily living. In doing so, he reminds us that the genre of memoir, a form increasingly bogged down in the luridness of grotesque particularities, still has the potential to transcend the sheerly confessional and to engage with the larger mysteries of the human condition.

Three distinct elements compose the structure of Greenberg’s book. The first and most apparent of these is the family drama surrounding Sally’s breakdown. Stationed between descriptions of the girl’s summer-long confinement at Bellevue are portraits of the author’s failed marriage to Sally’s mother, Robin, a flighty, New Age creature who operates a bakery in Vermont; his turbulent second marriage with Pat, a moody, avant-garde dancer desperate for her step-daughter’s affection; and his older brother, Steve, whose thirty-year battle with mania has rendered him friendless and dysfunctional. Greenberg exposes his loved ones down to the bone. His sincerity is almost cruel when he describes Robin’s efforts to treat her daughter’s disease with “Polarity” massages and drops of “flower extract,” or when he says of Pat that she is not really Sally’s mother and never will be. However, the author reserves his most brutal candor for his own conduct: the matter-of-fact tone with which he writes of slapping Pat during an altercation, and later shattering their bathroom door in an explosive rage while she telephoned the police from the bathtub, reveals a willingness to share even his most intimate shortcomings. Unlike many other contemporary memoirs of psychiatric adversity—those of James Frey and Augusten Borroughs immediately come to mind—the revelation in Greenberg’s writing never feels self-serving or exhibitionistic, merely authentic. Ironically, the one glaring exception to his honesty is in his inattention to Sally’s sexuality; we never acquire a sense of whether Greenberg’s daughter is a physically attractive young woman, or if she is concerned that her disease might impact upon her choice of a mate, although it is difficult to imagine the American teenager who is not concerned with romance. When Sally finally does acquire a boyfriend, out of thin air on the second-to-last page of the memoir, one cannot help feeling that earlier yearnings and disappointments have been concealed from us. But that, I suppose, is a father’s prerogative.

The second component of Greenberg’s account is a far-reaching and nuanced series of historical and biographical anecdotes about bipolar disorder. This is the volume’s intellectual foundation, reflective of the author’s extensive reading in the field, but these asides—about Hemingway, about Schumann, about Robert Lowell—never feel intrusive. Writing in The New York Times Book Review, Rachel Donadio, who is particularly smitten by Greenberg’s take on the relationship between James Joyce and his manic daughter, Lucia, describes the author’s style as “The Talk of the Town as if written by Dostoyevsky.” But what distinguishes Greenberg’s prose from Dostoyevsky’s—or, for that matter, from the brilliantly erudite Kay Redfield Jamison’s—is that one never senses that one is reading a work of philosophical argument. This reflects an admirable restraint. Most authors who know a significant amount about an inherently fascinating subject feel an urge to share a large portion of their knowledge. In contrast, Greenberg flashes us glimpses of his gems—just enough to makes his point, but never a glimmer more. The result is a casual, almost fugue-like style that renders the chosen images and quotations truly indelible. For example, he sums up the entire history of modern psychiatry with the lone remark by Eugen Bleuler, the physician who coined the term schizophrenia, that “his patients were stranger to him than the birds in his garden.” One senses that Greenberg has mastered the literature of psychosis, yet has chosen this specific line—and this line alone—to express the comprehensive truth of entire libraries.

Few critics have commented at any length upon the third element in Greenberg’s story, a series of references to the news events of the day, possibly because these moments are far less conspicuous than either the family saga or the intellectual commentary. However, the punctuation of the author’s own tragedy with bursts of national disaster—the bombings of TWA flight 800 and the Atlanta Olympics, for example—reminds the reader that madness is not the subject of the memoir, but rather an example of the myriad ways in which we are at the mercies of fate. Greenberg announces this as his agenda at the outset. “It is something of a sacrilege nowadays to speak of insanity as anything but the chemical brain disease that on one level it is,” he writes in the opening pages, “But there were moments with my daughter when I had the distressed sense of being in the presence of a rare force of nature, such as a great blizzard or flood: destructive, but in its way astounding too.” The personal journey of this volume—and the source of its truth—is that it is not merely the story of a father coming to terms with his daughter’s illness, but of a man embracing his own vulnerability and impotence. Greenberg is like a veteran stage actor who, after having accidentally stepped into the orchestra pit, suddenly recognizes how many other times he has come close to such a mishap.

What Greenberg does have to say about madness is also refreshing. Much has been written about the relationship between bipolar disorder and creativity, a correlation argued anecdotally in Kay Redfield Jamison’s Touched With Fire and documented empirically in the innovative research of Claudia Santosa and Connie Strong at Stanford University. Hurry Down Sunshine makes no effort to discount these claims; in fact, although Greenberg expresses his reservations regarding the conventional belief that bipolar disorder is “the disease of exuberance, of volatility and magnetism and invention,” his mission in this work is not to disprove that mania was a necessary prerequisite for the poetry of Byron. Instead, his message is that none of this genius is particularly relevant to his own daughter. Much as Hannah Arendt wrote of the “banality of evil” in her account of the Eichmann trial, Greenberg offers us a window into the banality of mania. Sally Greenberg is quite ordinary, despite her illness. Her father’s goal is not for her to live an extraordinary life, merely for her to fit in. The author drives home this point with a reference to the Hemingway short story “Soldier’s Home,” in which a young doughboy named Krebs returns home from World War I many months after the fighting. Greenberg quotes Hemingway as writing, “His town had heard too many atrocity stories to be thrilled by actualities.” In his own narrative, Greenberg offers us the actualities: the hours of empty time waiting in the dayroom on Sally’s ward, the cost of filling her prescriptions without insurance, the need to balance her care with earning a living or purchasing groceries. As anyone who has witnessed the illness or death of a loved one understands, the world does not stop—it should, but it never does, not even for a moment of silence. I cannot help thinking of the anomic Meursault in Albert Camus’ The Stranger, who visits the beach shortly after the death of his mother. How can a man sunbathe, we ask, with the soil still fresh above a parent’s grave? How can Michael Greenberg write a screenplay—or a memoir—once his daughter has been struck mad? Are we not all mad for attending to our daily chores while our very existence hangs like a chad? The magic of this book is that it accepts this discordance without condemning it.

Not far from the surface of Greenberg’s memoir is an exploration of our culture’s schizophrenic attitude toward free will and personal responsibility. I have chosen the term “schizophrenic” with care—for our thinking on the subject is often loose, disorganized, contradictory, and characterized by both delusion and indifference. This is particularly true regarding our attitude toward the relationship between identity and mental illness. Greenberg emphasizes that while our society has embraced the disease model of mental illness, many of us still place some degree of blame upon the patient and her upbringing. (Even our language rejects full integration into the medical model: as Greenberg states, “One has cancer or AIDS, but one is schizophrenic, one is manic-depressive . . .” The Greenberg family initially conspires to keep Sally’s condition a secret, much as elderly couples sometimes whisper the word “cancer” in shame. As Sally’s brother, Aaron, explains, “There are people who if they find this out will see her as an eternal mental patient and nothing more.” In our smuggest moments, we may condemn such thinking. Yet our nation’s prisons swell with those who have committed bloodshed under the spell of psychosis, and our streets contain thousands of victims shunned by their kin. One cannot help reflecting that all that separates Sally from a life on the streets is a middle-class family who can afford the emotional and economic costs of protecting her. The “majestic equality of the law,” as Anatole France once wrote, “forbids the rich as well as the poor to sleep under bridges.” In comparing his daughter’s fate with his brother’s, and with the many victims who lack her unwavering support network, Greenberg reminds us that her survival, much like her affliction, is as much a matter of circumstance as of willpower.

Hurry Down Sunshine is one of those extremely rare works of literature that operates well as both a love story and a social indictment—without either aspect interfering with the dramatic force of the other. As a love story, the devotion that Greenberg feels for his daughter pulses on every page. It is also infectious. We see so much of Sally’s naked soul—and it comes across as a generous, witty, tender, and insightful soul—that we cannot help loving her ourselves. At the same time, Greenberg’s book is about social justice. If we abandon our mentally ill to their fates, or hold them accountable for their psychoses, we do so because it is convenient, not because it is just. As a civilization, we will be judged upon the manner in which we treat our most vulnerable: our impoverished, our prisoners, our mentally ill. Finally, Greenberg’s memoir is a reminder that, no matter how many precautions we take, any of us might wake up one summer morning with a mad child. Or on TWA flight 800. As the author warns his brother, who insists that schizophrenia can be detected in the womb, there is “no marker” and “no blood test”—not just for madness, of course, but for calamity. Every day, through every performance, we live in perpetual danger of stepping into the orchestra pit. Yet we enter, stage center.