Sigutė Chlebinskaitė, Mindaugas Kvietkauskas, and Nissan N. Perez, eds.

Sigutė Chlebinskaitė, Mindaugas Kvietkauskas, and Nissan N. Perez, eds.

Institute of Lithuanian Literature and Folklore, Vilnius (€34)

by M. Kasper

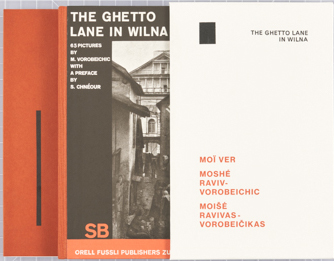

Exquisitely designed, printed, and slipcased, this two-volume set includes a hardbound facsimile of The Ghetto Lane in Wilna, a masterpiece of book art from 1931, along with a companion paperback of bilingual essays. Deservedly, it was on the shortlist for best exhibition catalog in Aperture’s PhotoBook competition last year.

The heart of the matter is the little facsimile. The work, still so fresh and original, first came out as one in a series of inexpensive photobooks issued by a left-wing publisher for middle-class and working peoples’ self-education. A total of 12,500 copies were printed, with the texts in three bi-lingual versions: English-Hebrew, German-Hebrew, and German-Yiddish. A slightly enlarged reproduction of the German-Hebrew version was published in Berlin in 1984. This new facsimile, of the English-Hebrew edition, is much more faithful, truly duplicating the size, binding, and feel of the original.

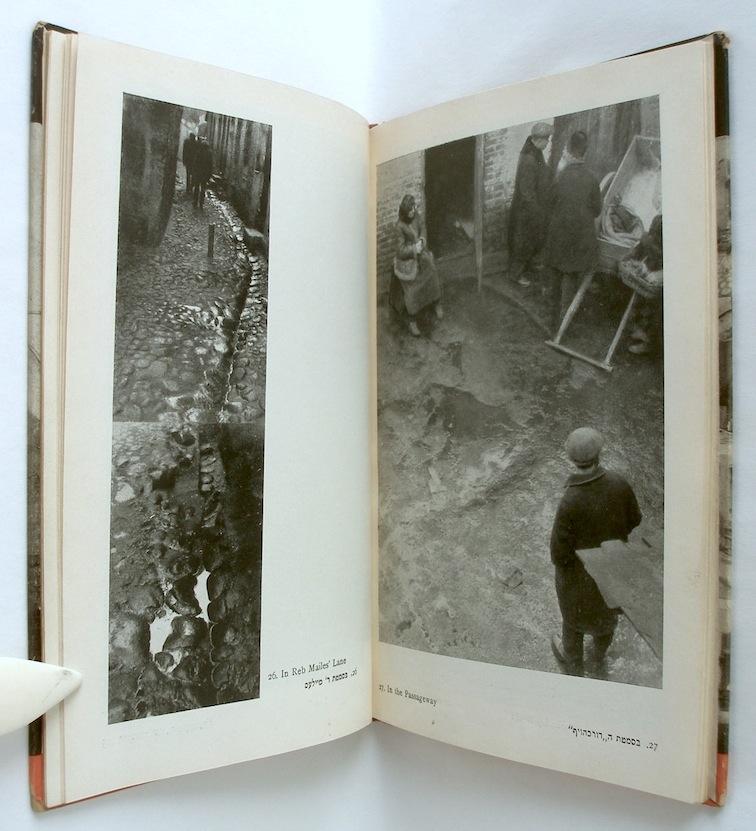

Both the original and this edition are modest in appearance and format, measuring just 7¾” x 5⅛”. Counting the cover, there are 65 black-and-white “pictures” (some with a single photograph, some with several) of streetscapes and people in the old Jewish quarter in Vilna, Lithuania. Each image is accompanied by a brief title or caption, usually simply descriptive, but sometimes grander (“Man and Architecture”). The work was inspired, probably, by the Yiddish playwright An-Sky’s project to archive the dying Jewish cultures of the Russian Pale, earlier in the century, but the Wilna photos were shot, cut, combined, and placed on the pages in ways that make it much more than merely documentary.

The sequence of images hints at narrative. It’s as though we’re strolling through the neighborhood, looking up at architectural details on the rundown buildings, then down into puddles on cobblestoned streets, and then observing people—mostly old, poor, and threadbare—as they go about their business. Ten years before the pictures were taken, 80 had died there in an anti-Semitic pogrom; the celebrated Yiddish author Zalman Shneur’s sentimental preface to The Ghetto Lane in Wilna mentions neither that, nor, indeed, much of interest about the images that follow. The pictures more than make up for any lost background, however. They include brilliant collages and montages in the manner of the times, but even more surprising and memorable are the photos cropped by the artist into geometric discs and slices, or curvy shapes, and laid out with lots of white space around them. Above all, this is unique and noteworthy page design.

Although The Ghetto Lane in Wilna is only occasionally mentioned in histories of photography and collage, it was widely admired in European avant-garde circles before World War II (when most of the print run was destroyed) as a vibrant, distinctive album of exotic imagery and innovative, cinematic mise-en-page. Leafing through it now, the cut up pictures have an even deeper, more sorrowful significance as an eerie prefiguration of the Nazi dismemberment of European Jewry.

The prefiguring artist was Moyshe Vorobeychik (1904-1995), a young Jewish Bauhausler then resident in Paris who was studying photographic technique. In 1929 he went home for Passover and took the photos with his new Leica. Emil Schaeffer, the adventurous owner of the publisher Orell Füssli Verlag, saw some on exhibit at a Zionist convention in Zurich, and brought the book out in 1931. It was credited to “M. Vorobeichic,” a variant transliteration of his name.

That same year, a second stunning photobook by Vorobeychik came out, entitled Paris. Larger in format than Wilna, with an introduction by the famous painter Fernand Léger, it’s another album of urban images, but different from its predecessor. The pictures are semi-abstract, almost tactile montages of places, people, and traffic, multiple exposures and sandwich prints mixed into an engrossing, evocative portrait of a big city on the go. Paris was credited to “Moï Ver,” a short form suggested by André Malraux so Vorobeychik’s name would be easier to pronounce.

There was a third album, Ci-contre (Facing Page), compiled soon after, for Franz Roh’s Fototek books, but, as Vorobeychik wrote laconically in a note to a curator at New York’s Museum of Modern Art in 1974, “it was not edited because of Hitler, etc.” The paste-ups, thought lost, resurfaced decades after World War II, but it took further years of effort by the artist and his family before Ci-contre was finally published, posthumously, in 2004.

Much information about the artist’s life and context is available in the elegant, illustrated companion volume to the new Wilna facsimile. In the first of two lucid essays of bio-criticism in both English and Lithuanian, Nissan Perez (who curated the Moï Ver retrospective at the National Gallery of Art in Vilnius, which this publication commemorates) summarizes Vorobeychik’s career and analyzes his artistic environments. In the other, Mindaugas Kvietkauskas digs deep into Vorobeychik’s early art education in Vilnius, before he left to attend the Bauhaus. Both scholars have mined family papers in Tel Aviv and Montreal, among other sources, for fascinating background details, to which they’ve added insightful commentary. These articles add a great deal that’s new and useful to the sadly meager literature on Vorobeychik.

Also included are a comprehensive chronology, as well as previously unseen photographs and copies of documents—including, most marvelously, Vorobeychik’s contract with Orell Füssli for The Ghetto Lane in Wilna. “The publisher hereby acquires the rights for all editions and issues,” it reads, “but if obligations remain unfulfilled, the publisher is authorized to find a substitute and deduct its cost from the publisher’s fee.” Thankfully for us all, the artist delivered.