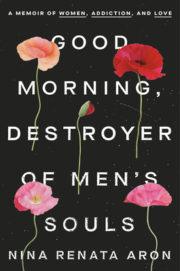

Nina Renata Aron

Nina Renata Aron

Crown ($27)

by Erin Lewenauer

“Living with a junkie involves a lot of effluvia. Everywhere, there are oozes that must be wiped away,” writes Nina Renata Aron in her gutsy, searing addiction memoir and first book. She dips and swoons through the darkness, freedom, and close encounters that add up to, for her at the time, a risk worth taking. Aron and her paramour K live together amongst their secrets in Oakland. He's always short on money and she can't tell if he's working at all. “His waking hours are careful calculus. To get from sunrise to sundown, he needs forty dollars—thirty for heroin and ten for crack.”

The timeline of Aron's story shifts as it does in many an obsessed mind. Her writing is verbose, harsh, and absorbed in place. With some pop psychology under her belt and in the throes of revenge, she’s intensely focused on portraying K’s "monstrousness" but also their shared passion. “It was an old-world romance, loud and lively—roaring with violent uncertainty—into which some tears and some lies were bound to fall,” she writes.

When K reappears in her life, she has a two-year-old and a two-month-old. He's sober when she leaves her husband for him—until, of course, he's not:

Sobriety, it turned out, was not a thing I could expect from him. The things I could expect, however, seemed to be the important things, to me, perhaps sadly, the only things—protection, fun, laughter, extraordinary sex. Drinking Slurpees together in my car on a street corner was pure joy. The once soul-deadening errands that defined my days—food shopping, dry cleaning—were, with him, extravagantly entertaining.

Her story then travels fifteen years earlier, before the blood, to when they met in 1997 at San Francisco's Tower Records where then-18-year-old Aron worked. She came to San Francisco in a fit of romance and to escape her parents' divorce with her three best friends from New Jersey: riot grrrls, into bands and piercings. She was busy crafting her image, as a young adult does. K waltzed in, in his twenties, “the tender tough guy” abused as a child. He’d had cancer and the opiates prescribed began his addiction. “I wanted to curl up in that warm coat pocket and be moved by the weight of him,” she writes, “all over this city I didn’t yet know.”

Aron details her long history of protecting addicts and codependency. Her older sister Lucia has "star quality" and a heroin addiction; “I carried her secrets around like a backpack full of body parts, guilty, angry, and exhausted.” She helped her parents by digging into her sister's privacy, but it came at a cost. “There was something intimidating about the way she held her secrets. Addicts are like celebrities or politicians in this way—the information they share is carefully controlled and you can never entirely trust it.”

Aron’s writing is gripping, filled with intricate loops of pain and anger. Despite her toughness, her "ironclad feminist politics", she asks, “Why did taking care of other people feel so good and hurt so much?” Even though she has educated herself on addicts and codependents, she's stuck in the spiral, alongside her tight-knit Jewish family and their house in emotional disarray.

Some of the more fascinating parts of Aron's memoir are when she ties in her graduate studies of Russian literature and feminism. "Love is women's work," historically, she notes, nestled between her descriptions of all the gory details of living in the shadow of an addict you're in love with, all the flashiness and danger. She never short-changes the freedom of youth and the deep knowledge that it's fleeting. It's enlightening to witness Aron claim her experiences and come to terms with herself: “Full-tilt me was crooked-faced, stormy, and dark. A slutty, sloppy Modigliani in sunglasses.”