Edited and translated by Theodoros Chiotis

Edited and translated by Theodoros Chiotis

Penned in the Margins ($15.99)

by John Bradley

“The [Greek economic] crisis was not simply financial,” writes editor and translator Theodoris Chiotis in his introduction to Futures: Poems of the Greek Crisis; “it was the dissolution of a fantasy of a world that perhaps never was.” The destruction of this “fantasy”—of a democratic society fully integrated with the European Union—understandably leaves anger and bitterness in its wake, as the poems in this anthology demonstrate. In work that varies greatly in style and structure, from prose poems to villanelles, forty-one poets offer seventy-eight poems on the psychological and emotional effects of the Greek economic turmoil.

Dissolution is an apt rubric for Chiotis to use, and it can be seen in many of the titles of poems in this anthology: “Incomplete Syntax,” “Poem to Be Recited at Protest Rallies When Riot Police is Twenty Metres Away,” “Small Poem in Memory of Suicide Victim Dimitris Christoulas,” “Homeless (Roof-less),” “The Chaos,” and “The Invisible Man or Plan for a Revolution.” Dissolution can be found as well in the imagery, as in “The Table,” by Vassilis Amanatidis. Once a symbol of coming together, the table now “gradually dwindled into a furniture, / that was imperceptibly torn to pieces.” And it can be found in fractured language, as in Steve Willey’s “Blood Poem”: “That half of my Greece is called blood is my poem.” Dissolution even threatens to unravel poems. In Yiannis Stiggas’s “The Road to the Newspaper Kiosk,” we learn: “—this is where a line with hammers is missing—.”

The dissolution of a nation leads to despair and violence. George Ttouli, in “Mutilated Images,” uses a litany to show social upheaval:

In Lefkosia they open fire

on politician’s motorcades.In Lefkosia I threw my passport

on the burning placardsWhat? What am I trying to say?

In Lefkosia I watched a cockroach

crawl beneath the barricades.

Often a dark humor emerges, as in A. E. Stallings’s “Austerity Measures,” one of two villanelles (both by Stallings) in the anthology: “Weep, Pericles, or maybe just get drunk. / We’ll hawk the Parthenon to buy our bread.” Absurdist humor also appears in three striking prose poems by Thomas Tsalapatis: “Transparent,” “The Nail,” and “The Box.” In “The Nail,” our narrator tells us how a nail grows from his forehead. Doctors eventually solve the problem: “They hung a painting on my forehead.” This absurdist solution has a drawback and an advantage—the narrator can no longer see anything other than the back of the picture, but the consolation he finds is “it’s not like that there is anything special to see.”

Social breakdown can also lead to defiance. “And if only death and nothingness are the only things left for us / Then in death and nothingness we shall find hope,” writes Nikos Erinakis, in “The New Symmetry.” In “Days To,” a poet who goes by the name of Universal Jenny offers advice, such as “Push over the cliff whatever’s moving your way,” “Neutralise the verb ‘to shock’,” and “Draw courage from zero.” Katerina Iliopoulou, in “In Heaven Everything Is Fine,” sums up why we turn to poetry at a time of crisis: “Words are a means of survival.”

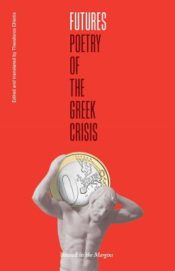

Much thought has gone into the creation of this book. Chiotis wrestled with the issue of “Greekness” and decided to include “not only Greek poets but also poets of Greek descent . . . and poets who have a personal connection or affinity with Greece.” The titles of each of the five sections of the book employ “financial jargon”: “Assessment,” “Adjustment,” “Implementation,” “Singularity,” and “Acceleration.” Chiotis also features, at the start of each section, a photograph of Greek street art; one shows us an image of Cupid, with the message: “fuck February 14th” and “Make Love & Class War.” The cover art is also arresting, displaying a marble sculpture of Atlas bearing on his back not the world, but a large Euro coin with the value of “0.”

There is one problem, however: Most of the poems in Futures are translated by the Greek poets themselves. And many of these self-translated poems contain badly worded lines. For example, in Emily Critchley’s “Protest Song, 11th December 2010,” she states: “Police are people too— / have so much feelings to give—” In Constantintinos Hadzinikolaou’s “The Adelaides,” he writes, “She goes and find him . . . .” In Yiannis Stiggas’s “In the Style of Y. S.,” Stiggas offers: “it is poetry to that kicks at the stool.” It’s unfortunate that these problems weren’t caught because when writers experiment with breaking grammar and syntax for effect, as many of the poets here appear to do, errors leave the reader wondering what fractures are deliberate.

This minor issue, however, does not dim the power of these poems. “I want to gatecrash history,” reads the graffiti in one photo. This impressive anthology does just that.