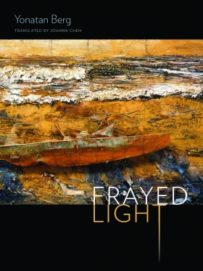

Yonatan Berg

Yonatan Berg

Translated by Joanna Chen

Wesleyan University Press ($14.95)

by Gwen Ackerman

Yonatan Berg’s book of poetry Frayed Light frames a slice of Israeli life rarely encountered by outsiders. The collection presents a personal story beyond and behind the news: the experiences of a young man who grew up in a West Bank settlement and served as a combat soldier before becoming a poet and bibliotherapist.

The snapshots of life offered in the poems are as clear as if shown on an LED screen: They are sharp, warm, compassionate and often breath-stoppingly awful. Don’t believe everything you see and hear, this book screams out; reality is the light that is frayed, and when looked at from different perspectives, may turn out to be the opposite of what was initially believed.

The book is divided into five sections; the first: “Hands that Once Held Manna” starts with a poem titled “Letter to the Reader,” in which Berg acknowledges the contradictions and horrors the book offers, and adds:

I apologize to each and every one of you

that I cannot touch, cannot reach out

to ease your pain, cannot hold you to me,

knowing I will ruin it all by saying something about the self—

something too flowery, too sophisticated.

The poems, originally written in Hebrew, come across beautifully in Joanna Chen’s exquisite translations. Read aloud, the melodies of the very different languages meld into one that is both multi-national and personal.

In “Ramallah Through the Window of a Bus,” Berg puts the reader next to him on a ride home through the Palestinian city of Ramallah, sharing the tension and ambiguity he feels as he stares at his Arab neighbors:

Perhaps they are remembering the old house,

the lost garden. We do not fall asleep on the bus.

Our fingers drum of their own accord

to that other rhythm—loose and wild.

Years later, I would be lying if I said

there was no contempt back then, no

creeping fear, but it came from outside,

never from within . . .

In “After a Night in the Alley of Worshippers,” Berg paints the monstrosity of war in what might seem like a mundane act: volunteering to collect the bodies of three Palestinian gunmen killed by his unit as they defended the Jewish worshippers under attack. While the reader recoils in visceral reaction to the scene described, what they don’t know is that four Israeli soldiers (among them Berg’s close friends), five Israeli policeman, three Israeli civilians, and three Palestinians were killed in that clash. Berg relives the trauma in affecting verse:

But when we got there I could not,

I simply could not. To this day I see Vish and a soldier,

shoving them into the armoured truck. They are dropped,

are dragged, I don’t have a better image for all this:

the bodies dragged, dropped,

over and over.

This is poetry that denies a label, written with such specificity that it resonates for us all. Nowhere is this clearer than in “To My Mother,” in which Berg speaks for every grown child who has left behind his family home and traditions:

You hand me a clean handkerchief,

ripe figs. I have been moving awayfor years, finding you before bedtime

tucking the blanket around me, singingof angels who watch over children.

Frayed Light offers a slideshow of conflict, family, and growing up, all seen through the lens of one man’s musings and illuminated by thoughts willingly offered up for inspection.