Interviewed by Anne Kniggendorf

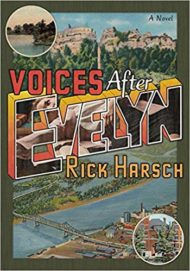

Although known as a master of Midwestern noir, Rick Harsch is adamant that his most recent publication is not a crime novel. The author of the acclaimed “Driftless Trilogy,” he recently released his ninth book, Voices After Evelyn (Maintenance Ends Press, $19.95)

The story is firmly planted in the aftermath of a kidnapping in La Crosse, Wisconsin—real-life teenager Evelyn Hartley disappeared on October 24, 1953. Hartley was babysitting when someone broke in through a basement window. Harsch imagines the girl “unversed in panic simulating a scream no louder than the radio” after hearing “a foot slide across the basement’s floor . . . her uncivilized grasp of danger distorted by a cultivated belief that fails to destroy the hope riveting her to her chair as the wolf charges up the stairs in its death rush.”

Harsch taps into that community’s collective feelings and mostly unspoken thoughts about the crime, which is assumed to have been a murder. In his telling, one classmate, Adele, appears to split in two, going by the name Stella for most of that year even as she dives deep into a relationship with Bobby, a man more than fifteen years her senior. As an adult, Adele gains local notoriety for imprisoning a man in her basement. Speaking by phone from his home in Izola, Slovenia, Harsch says these poignant plot-points are unintentional, making the ones that were all the more electric and thought-provoking.

Anne Kniggendorf: What would you say your new book is about?

Anne Kniggendorf: What would you say your new book is about?

Rick Harsch: It’s about what people really lived like in the United States in a small river city in the 1950s. And to some degree, about the rippling effect of a generational type of crime, the type of crime that makes people stop and take a look at how things have changed in their town.

AK: What do you mean by “a generational type of crime”?

RH: The kind of shocking crime that happens rarely. But it’s not a true crime novel in the sense that most people who want to read a true crime novel hope it will be. It’s not about solving the crime, it’s about the ways that people react to the crime and the thematic importance of the crime—when the town realizes that they can no longer save their babysitters from their wolves.

AK: I heard that you’re categorizing this book as an oral history. Who did you talk to? How do you think of it as an oral history?

RH: I don’t think of it as an oral history—I think of it as a novel. It’s a novel presented as an oral history, but the voices are all mine. However, I talked to a lot of people—I did a lot of research, and got a lot of stories from people who grew up there. If you look at every single event in the book, from minor things in a coffee shop to major things like the wife who sleeps with whoever shows up first, about half of them are probably literally true. From what I know, all of the bars actually existed. The train station bar, called The Spot, that would deliver the drinks on a toy train? That existed. The Coo Coo Club existed, and it had the air vent in the floor to blow ladies’ dresses up and had the dildo in the bathroom to humiliate women who grabbed it. That’s all true.

AK: Why did you have to tell this story?

RH: The first novel that I published was the fourth one I’ve written. I was really happy because the third one I’d written, which still hasn’t been published, had been finished and came out just how I wanted it, but I was still at the Iowa Writers’ Workshop and I had all this time left. So I came up to La Crosse and talked to a friend of mine, a guy I used to drive a taxi with, and he was telling me a bunch of typical taxi stories, and in a couple of months I wrote The Driftless Zone. The stories were just overwhelming, and all these stories were piling up and were all connected. But more specifically, the father of a friend of mine was alive during that time, and we talked about how he went a couple of times on searches for clothing or body parts or whatever—he was a really whacky old guy about the age of [the character] Bobby. So he turned into a character and that’s what did it more than anything. The background, or the environment, was built through all these stories.

AK: So the book was more character-driven than driven by the plot point of the murder?

RH: Yeah, but the murder comes with . . . It’s all like a bad joke. My favorite is the “My car is okay” business. That really happened. I knew a guy, and he’s in there, Gerard—he’s maybe ten years older than me—and he remembered with great pride being taken with his entire family to a gas station, and he said he never forgot how proud he was that they got his sticker. Their car was “okay”—they had nothing to do with the crime, and a gas station attendant proved it. I have no idea what that has to do with character . . . It may be the whole reason why Bobby worked at a gas station, I can’t say for sure. You’ve got to think about what would you do if you were working at a gas station, and they told you, “Check the trunks for blood and any other evidence, and if it’s okay, put this sticker on there.” How would you have felt at the age of 17 or 25, you know?

AK: I don’t know. That’s a weird thing.

RH: I would have been drunk with power. There was that, and then the decision to give every single adolescent of university age male a lie detector test. They really did hire a crazy outside investigator and didn’t fire him until he’d already done a horrible job. There’s a nonfiction book about the case with even more stuff I didn’t know, but a really good book remains to be written.

AK: I can’t help but ask about the structure of the book and your decision to include a chorus. What made you decide that the chorus was necessary?

RH: I think that’s a gut thing—instinct, intestinal. There are so many things that radiate from that crime, and a lot of strange things involved. For one, for a town its size, La Crosse produced two great film directors: Nicholas Ray and Joseph Losey. So there’s one thing, the cinematic connection. Then there’s Ed Gein. You know Ed Gein?

AK: No, I don’t.

RH: Oh, okay. Well, he’s the guy who Psycho was based on; he was Norman Bates. He was from La Crosse, but he lived in Plainfield, Wisconsin when he was caught. I don’t know how many people he killed, but he dug up bodies, and he had a mother issue. He would actually wear his mother’s hair and a dress and dance in the moonlight. Know your mass murderers! Ed Gein was probably one of the first nationally known killers. He used to live in La Crosse and when he was caught, two detectives from the Hartley case were sent to Plainfield to interview him. They were back the same day, so whatever clues they had, they were able to eliminate him immediately. There are still some people in La Crosse who believe that it was him.

Another part of the chorus, this is what this leads to, is that many, many people believe that they know where Evelyn is buried—at Losey Boulevard and Jackson, because it was under construction at the time. Or that Ed Gein did it. In the air in La Crosse there’s a chorus, there are all these beliefs about what happened. Then there’s the imagination, and I think it’s the second chorus that gets at this—envisioning Evelyn from the killer’s point of view, seeing her in the house and watching her. When something like that happens, it’s such a vivid event. A town where, as soon as this happened, people who couldn’t afford drapes put newspapers up. Nobody worried about their windows at the time, and then you have something like this, a very stark, simple visual crime—people imagine what happened. The combination of all these things made me put in a chorus.

AK: In a lot of places you have somebody saying that a disaster is either diverted or forestalled by hope, and so there’s this collective feeling—I don’t know if it’s disbelief, or ignorance, or wishful thinking, or what it is exactly, but what does that choral sense of hope say about this world you’ve created?

RH: I don’t see the hope.

AK: Oh, really?

RH: In my own feel for the book, the hope is in the transgressions of the characters, their freedom.

AK: That they’re continuing to live and do as they please, you mean?

RH: Not all of them, no. They’re going on with their lives, but it’s not as opposed to doing something about crime. It’s not set up that way. For instance, you have the relationship with Bobby and Stella, which is transgressive. There’s hope in that—hope in flaunting, so to speak, the rules, and behaving freely. That’s where I see hope. Also, I guess, in the manic joyful moments that people actually had in the ’50s. We probably have a similar notion of the ’50s—these very powerful images from one or two television shows, the Father Knows Best type of thing, that probably you’ve never seen. Neither have I. It’s the Eisenhower dull ’50s, just as the United States kind of collectively went to sleep and made money off the interest. It actually was a pretty vibrant time with also a great deal of social difficulty. There were still problems with the enormous number of people back from the war and trying to make lives for themselves. The ’50s were a complicated social decade, but you know, in any particular place that you’d go, you’d find people of lesser means having a hell of a time whenever possible, which may be just the way life is anyway.

AK: Part of the transgression business that you’ve mentioned . . . Is there guilt in that? Anybody could be guilty of killing Evelyn, right? And there’s so much guilt over the transgressions as well. Does it feel to you like everybody’s implicated?

RH: On one level, yes; what Steve says on page 70-71 (that “everybody is fucking guilty”) is more or less how I view it. What he’s talking about is how the people of note, the people of power, the people of hand-wringing, the people of conventional thought, don’t question what they’ve done, as we don’t question what we’ve done with civilization. I think what he says is “Why leave the forests if this is the best you can do,” you know, we can’t even protect our babysitters. And so, it’s a criticism of the entire civilizational structure. I’m always interested in how women read the book, because in my mind, it’s a nice stick in the patriarchal eye. But I don’t always get that response. For some—and it doesn’t seem to matter in terms of gender—Stella is the favorite character. In the end however, Stella fails; as a fifteen-year-old, she acts like a high school girl for a moment, gets caught up in the high school fight. Yet that’s the worst she does. Otherwise, she’s rather wise and strong. So is she guilty? She has her one-night stand, and she revels in it, and she has, to my mind, the sanest view of it. Maybe better not to tell Bobby, but Bobby would probably be okay with it anyway. What’s been hurt? Nothing, it’s been a great night. Does she want another night with Louis? Maybe in a couple years. She puts it all in perspective and sees nothing but the beauty in it.

AK: Why is the character Adele only referred to as “Stella” when she’s younger? I know Bobby nicknamed her that . . .

RH: That’s why.

AK: It seems so pointed, as if they’re two different characters. She’s so young . . .

RH: That’s inevitable. She really is two different characters, and mainly because of . . . This would be sort of a book secret, I guess, but to me, she’s the one who embodies the change wrought to the town. She’s the character who’s the most clearly affected by that time period.

AK: Adele is a pretty creepy woman—the business of keeping Larry in the basement. It looks like that has something to do with sort of retroactively taking control of what happened to Evelyn by locking the ghoul in the basement rather than allowing it access to the house like Evelyn’s killer.

RH: That’s nice; I never thought of that.

AK: I also wondered about Stella’s scream. She says she was able to suppress that scream only until Bobby was dead. There’s a lot about the scream in the text. Going back to the idea of generational crime, this seemed like a generational scream, and I wondered what your intention was with that.

RH: I think that’s the kind of thing you’re not supposed to ask writers.

AK: Oh, damn.

RH: To me, if the utter horror of the horrible is going to be expressed by anyone in that book, she seems like the most qualified.

AK: Is it generationally appropriate? Is that what you mean by her being the most qualified—her age and her gender and her proximity to everything?

RH: Yeah that, and that despite her age and her gender she’s the most free, her and Bobby also—they’re comrades in petty crime, but she’s precociously so. And we don’t know what Bobby was like. There’s a hint that he was in the war, but we don’t know what he was like when he was fifteen. But she’s ahead of the game, and she’s the most free, the most transgressive. What happens when the babysitter is taken is that they solve the crime or they don’t, but they never get to the underlying cause of it. That’ll never happen. It is a scream against life and civilization, and she’s got the most right to that.

AK: And by the underlying cause you mean the societal ill?

RH: Yeah, civilizational nonsense. Community makes a great deal of sense. It all makes sense. Two families get together because they can work a little less and earn a little more. That’s the start of it, and it ends up with what we’ve got. It’s horrific on every human level. There are those who, from early on, see or intuit that there’s just something wrong with these rules that we’re given, and violate them just by instinct— but with intellect. That’s why she has the conversations with her friends. That’s why she likes Evelyn, because Evelyn just happens to be someone who let her cheat. Of course, her friends are going to hate everybody on that economic divide. But she says, “Wait a minute, that’s unfair. She was nice; she let me cheat.”