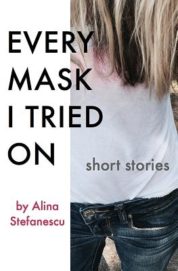

Alina Stefanescu

Alina Stefanescu

Brighthorse Books ($16.95)

by Ralph Pennel

In Good and Evil, Nietzsche argues that, “All great things must first wear terrifying and monstrous masks, in order to inscribe themselves on the hearts of humanity.” In her debut fiction collection, Every Mask I Tried On, author Alina Stefanescu does just that by means of critical analysis of the personal through the interpersonal, and by exploration of the self as an articulating component of literary craft, all in order to give shape to the “unshapable.”

In “My Name is Not Rita,” the third story in the first section, the author takes a discerning look at the creative process, especially the manner in which we render representations of ourselves. Immediately, we catch the narrator on the defensive, reclaiming herself against those close to her, those who profess to know her better than she does: her lover, the assistant at the radio station where she works, even the author herself. The lover, it is revealed in the first few lines, is writing a book about the narrator. The assistant at the radio station exclaims the narrator is two people, intimating the person she is on air is stronger than who she is off, that she “came across confident—bluegrass this, bluegrass that—but in the studio [she] looked tired and less full of life.”

It is in these renderings that we find the author struggling with representations of the self, though they resist such narrow definition at every breath. The author, of course, is all these characters (as the narrator was in the lover’s book), and is in conversation with herself about what the creative process reveals about how little we know ourselves—except, perhaps, in a character’s constant refusals of ever being known precisely, toiling on and on in the persistent ambiguity of discovery.

At the very end, the lover has moved to Maine and finally published his book. In the book is a dedication to Rita, whom he claims “inspired all of the characters,” a desire he expressed earlier, saying, “he wanted to spread me out into various characters” and that “you’re too much for one woman.” As the title informs us, however, the narrator’s name is not Rita, asking us to examine the failings of intentionality in process. From here, a blueprint is set for how to navigate the stories that follow.

In the fourth section, “There Was No More Blood than A Period,” Stefanescu takes on the approximations and distortions of language, how we rely on it to keep ourselves from disappearing all together. In “Wind Words,” for example, the narrator, a young girl, is translating the world as defined by her parents’ interpersonal communications, especially the ways they make meanings based on failures. Stefanescu sums up this experience at the bottom of the first page through the narrator’s own method of navigating gaps between the meanings of words; her voice, when attempting to speak her mind, “comes up just a tad shy of a somersault and no one but me is spinning.” How easily we take meaning for granted, that what we are attempting to communicate will be understood as we meant it to be.

The wind slips itself around the way we allude, the way we infer, the way we inflect. As it turns out, all words are wind words, “the way the wind rambles through all the words regardless,” even words as tightly wound as “knots.” All are porous. All mere reflections. All have room to squeeze more meaning through and from. But, as the mother of the narrator assures us near story’s end, “It’s okay when the boat rocks . . . It’s okay, we are at anchor.” No amount of wind will blow us so far off track that we will be lost to vast horizons, we will find common ground in a common language.

In the final section, “Not Without Some Pain,” the author reflects on the art of art in the story “The Romanian Part”—how we are art’s meaning’s messengers, and how, “What we see becomes the thing we can’t see past.” But what happens if what we can’t see past is the mask itself? “The Romanian Part” is smartly broken up into different sections with titles like “Her Best Romanian Child” and “The Kitchen Saudade,” in order to show the author’s intersecting identities as Romanian, American, mother, wife, author, subject and object, vehicle and mode. The perfect way to illustrate how, “What we make of a thing is the story of us. . . . If I weren’t dying of every symptom I google, I might find time to save this story.” Identity is fluid, layered, and complex, a myriad of masks we don’t even see until we remove them for the next, each story a thread in the fabric of the visage.

Alina Stefanescu’s debut collection of stories is a triumph of highest order, at times both “monstrous” and “terrifying” in its honesty. Every Mask I Tried On is a collection each of us must try on for ourselves in order to see more clearly the scaffoldings of our own invented artifices.