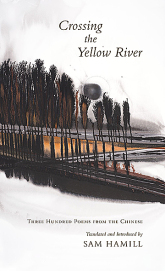

Three Hundred Poems from the Chinese

Three Hundred Poems from the Chinese

Translated and introduced by Sam Hamill

Tiger Bark Press ($24.95)

by John Bradley

“Every translation is a provisional conclusion,” Sam Hamill tells us in his informative introduction to this collection of Chinese poetry, which includes poems from 330 BCE to the 16th century. Later, he states again that a translation is “not a conclusion, but a provisional entryway.” It should come as no surprise, then, that Hamill is still revising his translations in this new and revised edition of Crossing the Yellow River, originally published by BOA Editions in 2000. Hamill wisely focuses mainly on the poets he most admires: Li Po, Wang Wei, and Tu Fu.

What is about Chinese poetry, especially the poetry of the T’ang Dynasty (618-907 CE), that has drawn so many translators over the years, such as Ezra Pound, Arthur Waley, Kenneth Rexroth, and Bill Porter, to name only a few? Here is W.S. Merwin’s explanation, from his “Preface”: “The great treasure of classic Chinese poetry is not composed of its variety of subjects nor even of a wide range of feeling, but of the depth and clarity and delicacy with which subjects—often familiar ones—and feelings are evoked.” Li Po’s “Questions Answered” offers a good example of that “depth and clarity and delicacy”:

You ask why I live

alone in the mountain forest,and I smile and am silent

until even my soul grows quiet.The peach trees blossom.

The water continues to flow.I live in the other world,

one that lies beyond the human.

Simplicity and clarity shine in this resonant translation of Hamill’s. As Li Po (701-762) attempts to answer questions about why he would shun human company for a solitary life in a mountain forest, his response points to the beauty of the wild, yet that “other world” also speaks of an inner realm, a world of deep solitude that he can’t begin to explain.

As a translator, Hamill avoids rhyme but achieves lyricism. He strives for resonance and conciseness, avoiding exposition. To fully appreciate his craft, compare the above translation with this one by David Hinton. It’s the same poem, though Hinton entitles it “Mountain Dialogue”:

You ask why I’ve settled in these emerald mountains,

And so I smile, mind at ease of itself, and say nothing.Peach blossoms drift streamwater away deep in mystery:

It’s another heaven and earth, nowhere among people.

Both poets break the poem into couplets, but the similarities end there. “Emerald mountains” feels exotic, and the phrase “mind at ease of itself” explanatory. Hamill’s translation embodies the mystery, rather than states it.

Some of Hamill’s translations stumble at times, such as this line from Wang Wei’s “Deer Park”: “Refracted light enters the forest, / shining through green moss above.” How can the moss be located above the speaker? Is this a figure of speech, comparing the green canopy to moss? Or is this odd phrasing supposed to reveal an altered state of mind brought on by deep meditation? Or is it a mistranslation—does the sunlight graze the top of the moss rather than shine through? The questions triggered by the translation distract the reader from the poem. A minor glitch such as this, however, hardly mars this fine anthology.

Anyone who wishes to learn the craft of poetry or simply find nourishment in well-wrought language will be rewarded reading these poems. Whether it’s lament (“fish traps catch nothing but the stars”) or desire (“if my skirt should open, blame the warm spring wind”) or sly humor (“But when we make love beneath our quilt, / we make three summer months of heat”), these poems show how to capture human emotion with subtlety and depth.

As Hamill reminds us, modern poetry owes its birth to classic Asian poetry. Ezra Pound’s translations of Japanese and Chinese poems are problematic, to say the least, but they introduced a new kind of poetic, a “shorter lyrical verse rooted in imagism.” The poetry of H. D. or James Wright or Jack Gilbert could not exist without the profound influence of ancient Chinese poetry. Sam Hamill has done a great service in keeping these poems alive. May they live on, blossoming in new translations yet to come.