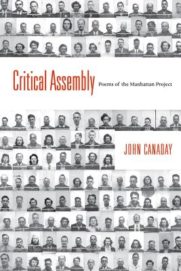

John Canaday

John Canaday

University of New Mexico Press ($19.95)

by John Bradley

“Longing to repeat God’s opening salvo, ‘Let there be . . . ,’ / they roughed out doomsday.” This is the voice of journalist William Laurence in “Medialog: William Laurence,” the opening poem of Critical Assembly, describing those who created the first atomic bomb. This poem, a ghazal, shows the skill of the author. John Canady, who won the 2002 Walt Whitman Award for his debut book The Invisible World, has not only done extensive research on a huge cast (forty-six characters deliver monologues in this book,) but he’s transformed the events and facts into engaging literary works, no small achievement.

Some readers might believe that we’ve already heard from the Manhattan Project’s major players, such as Albert Einstein, J. Robert Oppenheimer, Leslie Groves, and Edward Teller, among others. But Canaday shows us while we may know something about these figures, we most likely do not know the internal friction between many of those involved in the Project. Here’s physicist Edward Condon, for example, on the strict control of General Groves, who oversaw the physicists: “He would redact our very souls, friendships / and loves blacked out by censors’ pencil strokes, / our wives kept ignorant as aliens, / all of us thieves in his fiefdom . . .” Canaday’s Kitty Oppenheimer presents some of the most bitter lines, comparing General Groves’ stomach to “a pregnant sow’s” and asking at a party when she’s drunk, “’how does one get the come / stains off a nightie?’” Poetry has never given us a Manhattan Project quite like this.

Canaday also brings in many voices readers have never heard from before, such as Antonio Martinez, a lab assistant, who struggles with his identity: “How can I bear / a Spanish name and speak in English / yet keep my Tewa soul?”, the very breaks in the lines suggesting his inner conflict. We hear from Appolonia Chalee, a maid, who disapproves of the gadgets used by Mrs. Fischer, the woman she works for: “I tell her discontented / spirits live in these machines, but // Mrs. Fischer twists her husband’s arm / to buy more gadgets . . .” the word “gadget” reminding us of the atom bomb, which the physicists referred to with the same term.

Essentially a series of dramatic monologues, with each poem named after the speaker, the book can easily be imagined as a play. One of the more fascinating characters is Edith Warner, a woman who came to the Southwest in hopes the dry climate would cure her tuberculosis. She opened a tea room near the Rio Grande, where she offered food and respite for the nearby physicists. Her voice is the most connected to the land of all the speakers, and reading her poems, it’s easy to see why the physicists would go to her tea room for comfort: “I will pickle winter pears, tomatoes, squash, / and then lay out tobaccy Dukey, lemons, and sardines . . . . “ But she’s nobody’s fool: “I recognize / the conversation of atomic specialists; I know / the sound of German and Italian natives, what it means / when such men staff a secret Allied military base. / They think I disapprove. They’re right. But not of them.”

Another memorable character, due to his ominous tone, is that of Peer de Silva, head of military intelligence at Los Alamos:

Oppenheimer’s childlike trust’s

the worst. Milk and honey

for some egghead’s Eden

where bleeding-hearted

fellow travelers think trust

is “only decent.” Blind

faith’s poison, even

smacks of treason. Gimcrack,

geegaw sentiment at best:

cheap beads he’s set

to trade Manhattan for.

Ideology is war.

In a section of Biographical Notes that Canaday includes, we learn that after the war de Silva “joined the nascent CIA”—no surprise.

The speakers are not only critical about each other, however; many of them have misgivings about the “gadget” itself and their role in creating it. Rose Bethe, daughter of physicist Hans Bethe, tells us: “They [the Nazis] made us all commit our lives / to evil. Which, with a will, we did.” Brigadier General Thomas Farrell views humans as less than heroic: “Puny, / blasphemous things, we dare / tamper with forces heretofore / reserved to the Almighty.” Robert Serber, a physicist, offers these words, which could be an epitaph for the Manhattan Project: “Please God / we weren’t monsters. But we loved our work.” His honesty adds pathos to his plea.

These are heavily allusive poems, and while the notes at the back of the book help a good deal, this book will be a challenge for those unfamiliar with the Manhattan Project. However, an ambitious work of poetry like this—reminiscent of Campbell McGrath’s XX: Poems for the Twentieth Century, which also contains multitudes and monologues—should be celebrated. While Canaday’s book does not include the voices of those in Hiroshima and Nagasaki who experience first-hand the product of the labor at Los Alamos, these poems do allow us to hear the psychological toll that creating this bomb had on all involved, including wives and laborers.

Critical Assembly arrives at a crucial time, when we hear casual talk of using “strategic nuclear weapons” and staging a “bloody nose attack” on a nuclear power. Joseph Rotblat, the physicist who left the Manhattan Project after the defeat of the Nazis, refusing to do further work on the atomic bomb, offers this advice to himself: “Leave the lab. Seek /naïve work and save / the heart. Grieve.” His voice resonates now all too clearly.