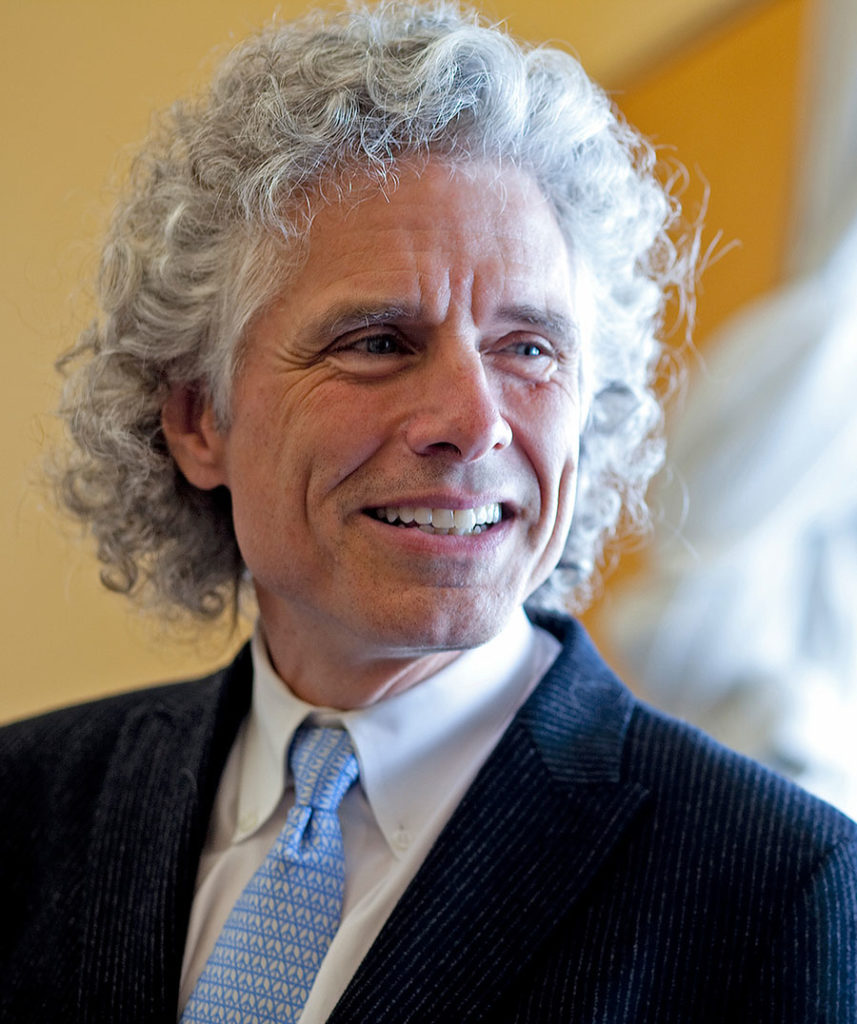

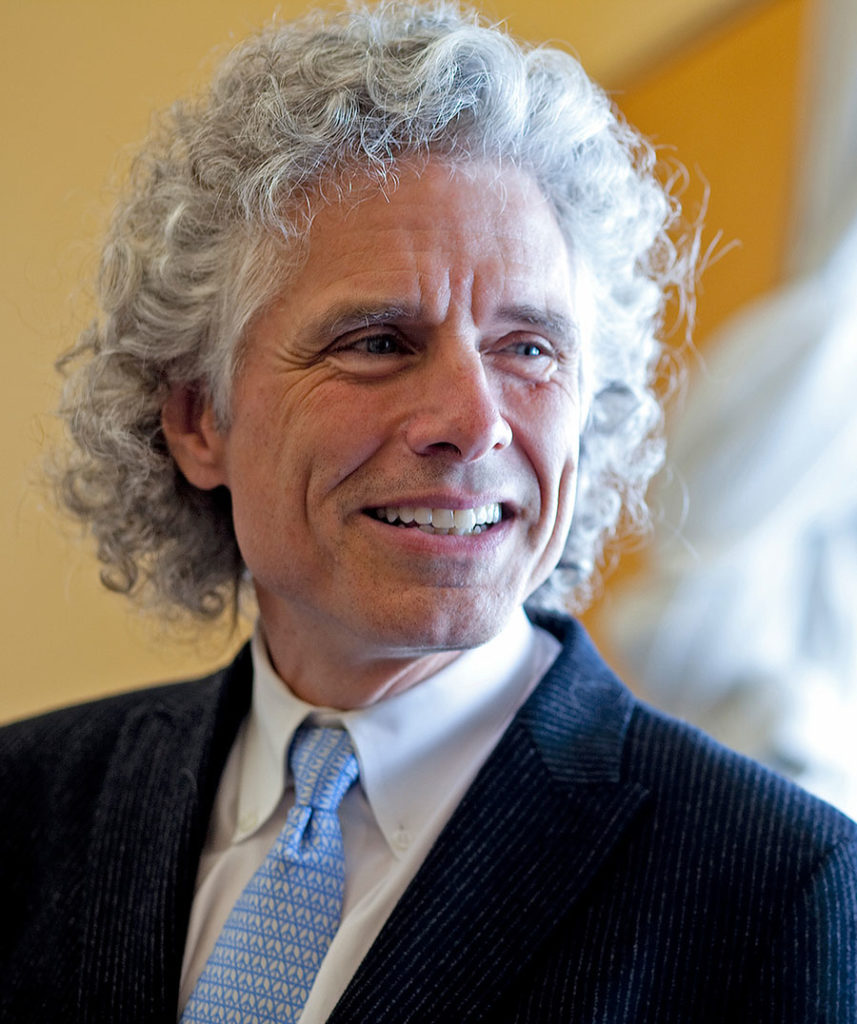

photo by Rose Lincoln

Interviewed by Allan Vorda and Shawn Vorda

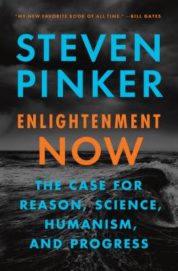

One of the most popular and widely read cognitive scientists of our era, Steven Pinker is the Johnstone Family Professor of Psychology at Harvard University, where he conducts research on cognition, language, and social relations. Pinker received his B.A. in psychology from McGill University in 1976 and his Ph.D. in experimental psychology from Harvard University in 1979. He later did research at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, where he taught from 1982 until 2003. He is the author of over a dozen books, including How the Mind Works, The Better Angels of Our Nature, The Sense of Style, and most recently Enlightenment Now: The Case for Reason, Science, Humanism, and Progress (Viking, $35).

Pinker was named one of Time’s 100 most influential people in the world in 2004, has been twice named to Foreign Policy’s list of top global thinkers, and was elected to the National Academy of Sciences in 2016; he has won many awards both for his books and his research, and he chairs the Usage Panel of the American Heritage Dictionary. Known for his long curly locks as well as for his impressive intellect, Pinker was voted in 2001 as the first member of the Luxuriant Flowing Hair Club for Scientists.

The following interview took place at the ZAZA Hotel in Houston on March 9, 2018.

Allan Vorda: What was the genesis for writing Enlightenment Now?

Steven Pinker: One source was my coming across data sets that showed the world had improved in areas beyond those I had documented in The Better Angels of Our Nature. That book, which came out in 2011, was itself inspired by my surprise at data that showed many measures of violence had been in historical decline, such as crime, war, and violence against women and children. That surprise led to me to the conviction that it was an underappreciated story waiting to be told, and it set the challenge to me as a psychologist to explain it. Why has there been so much violence throughout human history and how have we managed to tame it? Enlightenment Now came from a similar epiphany, namely the realization that it wasn’t just violence in which the human condition had improved, but measures of hunger, disease, child mortality, maternal mortality, literacy, work hours—pretty much every aspect of human flourishing has shown an improvement. Once again the vast majority of literate, educated people are unaware of these improvements and once again they demand an explanation. I suggest that the overarching cause for this human progress consists of the ideals of the enlightenment: reason, science, humanism, and progress.

Steven Pinker: One source was my coming across data sets that showed the world had improved in areas beyond those I had documented in The Better Angels of Our Nature. That book, which came out in 2011, was itself inspired by my surprise at data that showed many measures of violence had been in historical decline, such as crime, war, and violence against women and children. That surprise led to me to the conviction that it was an underappreciated story waiting to be told, and it set the challenge to me as a psychologist to explain it. Why has there been so much violence throughout human history and how have we managed to tame it? Enlightenment Now came from a similar epiphany, namely the realization that it wasn’t just violence in which the human condition had improved, but measures of hunger, disease, child mortality, maternal mortality, literacy, work hours—pretty much every aspect of human flourishing has shown an improvement. Once again the vast majority of literate, educated people are unaware of these improvements and once again they demand an explanation. I suggest that the overarching cause for this human progress consists of the ideals of the enlightenment: reason, science, humanism, and progress.

AV: Can you briefly describe these four major ideals?

SP: The commitment to reason amounts to our not trusting sources and claims to knowledge other than reason, such as dogma, sacred texts, authority, tradition, intuition, gut feelings. Every belief should be justified by reason. The companion value of science holds that the world is intelligible, that we can understand it by forming possible explanations and testing them empirically against the world. And the value of humanism is the commitment to human well-being and flourishing as the ultimate moral good, as opposed to the glory or preeminence of the nation, tribe, or faith, as opposed to obeying divine commandments, as opposed to achieving feats of heroic glory, as opposed to advancing some mystical force or struggle towards a messianic or utopian age.

Shawn Vorda: In Part II of Enlightenment Now, you explain how these ideals have led to progress in just about every single measure of human well-being. Bill Gates recently cited five of his favorite facts from this section, ranging from time spent doing laundry to a global increase in IQ. Gates also declared Enlightenment Now is now his favorite book of all time. Are there any facts regarding progress that you consider particularly promising?

SP: Certainly the rise of global literacy is promising. The fact that 90% of the people in the world under the age of twenty-five can read and write is unprecedented in human history. The decline of extreme poverty is also promising; the level of extreme poverty is less than ten percent, and the UN has set as one of its sustainable development goals the elimination of extreme poverty everywhere by the year 2030. Lifespans continue to rise and life expectancy at birth is increasing. Also the many technological innovations in the pipeline promise additional improvements in human well-being; these include energy technology, recycling technology, synthetic biology and rational drug design, genomics, and many others.

SV: Despite an increase in the literacy of the world, recent Pew results indicate an overall decrease in literary reading. Do you have any thoughts on these results? Have you considered producing your work through other media, such as podcasts or YouTube, where they might reach a wider audience?

SP: It seems these are happening at opposite ends of the literary spectrum. The increase in literacy pertains mainly to the children in the developing world who formerly could not read at all, as opposed to the literary elite who might be reading less fiction or literature. I have been struck by ideas I want to share, and how the world of non-text media has exploded. There are hundreds of podcasts, and YouTube videos seem to get greater circulation than text interviews and articles. People recognize me on the street because they’ve seen me in a YouTube video, and impressionistically that does seem to have increased. I suppose I would need numbers to know whether the increase in YouTube viewership came at the expense of people who would otherwise read, or if it consists of people who would otherwise be watching television programs or playing video games.

AV: In the chapter “Reason” you state: “People affirm or deny these beliefs to express not what they know but who they are.” In a polarized political society it seems we have come to a point where a political party puts their agenda ahead of the best interests of America. Essentially, a person might identify himself by saying, “I am a Republican” instead of saying “I am an American.” What can be done to limit this trend?

SP: I don’t know what can be done, but certainly identifying it as a prime source of public irrationality would be the first step; especially if a larger community of people can think about what can be done about it. I don’t have a prescription for turning around an entire society from the trends that have been following for the past twenty years. At least being aware of it would mean that some portion of the intellectual community, those that are not ideologically or tribally committed, are at least aware that all of us are vulnerable to it. Whether that can proliferate, go viral, or reach a tipping point, I don’t know. But there have been inroads against other forms of irrationality. People don’t believe in alchemy or unicorns or miasmas. There is an increasing number of people who are aware of the data revolution and insist on metapolls like 538.com, or sabermetrics in sports, or evidence based policy and medicine. It is nowhere close to a consensus, but it has certainly penetrated the awareness of many elite professions. Political tribalism as a source of irrationality is a new idea and I think it’s largely unknown. I think if it becomes better known, it sets the stage for us to take measures against it.

SV: Also in “Reason,” you discuss “The Most Depressing Discovery about the Brain, Ever” or “How Politics Makes Us Stupid.” Can you briefly describe the studies related to these articles?

SP: These were studies done by the Yale legal scholar Dan Kahan, who was a big influence on that chapter. The studies presented people with data from a fictitious study in which the first impression of the data contradicted the actual message of the data. That is, if you looked at the absolute value of the numbers but didn’t do a simple comparison of ratios, you could misinterpret the results. Kahan varied whether the content of these studies were politicized (the effect of a concealed carry law on violent crime) or politically neutral (the effectiveness of skin cream treating a rash). He post hoc divided his subjects into numerate, more numerate, and less numerate groups based on tests of mathematical ability. In the case of politically neutral content (the skin cream study), the more numerate subjects scored better than the less numerate subjects, regardless of left or right leaning tendencies. But when it came to political issues (the gun control study), each faction fell back on their primitive, innumerate impulses. The subjects were seduced by raw numbers and made mathematical errors if the results didn’t agree with their ideology’s favored position. It suggests that we’re apt to ignore evidence when it presents a challenge to our favored position, and we’re all too ready to accept evidence when it confirms it.

AV: Recent studies have shown that twenty-three percent of people are non-religious and the numbers are increasing every year. Nevertheless, when there is a political discussion on cable TV networks, they often talk about the religious right and the evangelical vote, but they virtually never mention the non-religious vote, which is almost a quarter of the populace. Why is this?

SP: In part it’s because religious groups are organized and they form effective voting blocks. They’re emboldened by their coalition and encouraged to vote in large numbers. Many of the so called “nons”—people without a religious affiliation—are not necessarily rational, secular atheists; rather, they’re people who have just dropped out of all institutions. They’ve not only dropped out of organized religion but also out of engagement with the entire political process. This is a regrettable development because it’s an example of how democratic politics is often pushed by the most energized interest groups, as opposed to the interests of the population as a whole. Perhaps it also speaks to the lack of political shrewdness of non-evangelical movements since they have not had the same success in mobilizing their forces and getting their faction to the polls. I also suspect a reason for the disengagement of so many center and left-wing voters is the left has joined in the Trumpist denunciation of mainstream institutions and his dystopian vision of American society. If you agree with Trump that the country is a cesspool of inequality, crime, police shootings, and racism, then you’re apt to figure there is no difference in the major party candidates. So it doesn’t matter if your president is Hillary Clinton or Donald Trump, because they’re both presiding over equally dysfunctional systems. One of the reasons I think it is essential to take note of the progress that has occurred, is so people don’t become cynical or fatalistic about our existing institutions, or perhaps tempted towards radical or nihilistic alternatives.

AV: Every day we wake up to news that is generally depressing. Your book is the opposite, since it presents a very positive outlook for our species, especially over the last couple of centuries. This seems to go against the grain of the “modern apocalypse” in regards to concerns of overpopulation, resource shortage, pollution, and nuclear war. What is the greatest existential risk now facing us and is there an existential risk that concerns you in the far future?

SP: I don’t know that the risk is existential, but climate change certainly poses a serious risk of disruption and perhaps human misery. If climate change disrupts the growth of food, forces wide-scale migration, and results in catastrophic tipping points like the diversion of the Gulf Stream, there could be wrenching changes. I doubt they would be existential, but they don’t have to be existential to cause great amounts of misery. The chance of nuclear war is something we should be concerned about, although I think the chance is small, but the consequence could be catastrophic. Again it’s too easy to leap to something being horrific to something being an existential threat. In the most extreme nuclear winter scenario, the threat could be existential, but that would require the exchange of hundreds of weapons. A single nuclear exchange would be far short of an existential threat.

SV: In a recent event we attended in Houston, both Sam Harris and Geoffrey Miller expressed concerns over the existential threat of Artificial Intelligence. Miller was specifically concerned with an ongoing “arms race” between China and the U.S. to develop AIs for defense systems. You explain in your book why you don’t share concerns regarding AI, but you do mention concerns regarding nuclear war. If newly developed AI is linked to our defense systems, is that not slightly concerning?

SP: I don’t think it’s more concerning than the systems we have now. In fact we have AI in cruise missiles and it’s a cliché of computer science that once a system starts to work we no longer call it AI. AI is reserved for computational challenges at the frontier of knowledge. So there isn’t even a clear line between AI and computer programming. There is a fantasy of a godlike artificial general intelligence that would be omnipotent, omniscient, and have the power to solve any problem instantly, and in some scenarios has a thirst for infinite power and influence. I think that’s fanciful. There is no evidence that current AI is on such a trajectory. It’s not clear that the concept of artificial general intelligence is even coherent, because intelligence requires knowledge in the domain in which one is reasoning. There is no reason to think that merely being intelligent is tantamount to seeking power and domination. The fear an AI system hooked up to vast infrastructure might be given a vague goal that would include collateral damage to humans is utterly fanciful, like giving an AI a task of curing cancer where it turns us all into guinea pigs for lethal experiments. I think if we were smart enough to design a system that could cure cancer, we would not be so stupid as to give it a blanket goal without programming in the various tradeoffs and considerations. Any system that is intelligent enough to accomplish anything of interest would be intelligent enough to consider all the tradeoffs and potential for collateral damage.

In general I think apocalyptic scenarios are accepted with too much credulity, whereas the reasons that apocalyptic scenarios don’t occur are boring and people don’t like to write about them. The previous apocalypse scenarios haven’t happened. We have never run out of a resource, and population is likely to plateau in the second half of the 21st century. The apocalypse makes for too enticing theatre to be evaluated rationally. The AI scenarios assume an utterly implausible handover of control to the systems, or an equally implausible megalomaniacal designer of the system, or a lack of control of the system despite the fact every interface with the real world has to be mediated with humans to make it happen.

SV: In “The Environment” chapter, you discuss the dangers of climate change and William Norhaus’ concept of a Climate Casino: if there is an even chance the world will get worse and a five percent chance of catastrophe, it would be prudent to take preventative action even if the outcome is uncertain. However, you seem less concerned with issues regarding resources. Could the same logic of the Climate Casino also be applied to concerns with resources, or other concerns in general.

SP: Yes, it could be applied to other concerns in theory. When it comes to resources, I think the concern is misconceived, because the model in which we successfully extract more and more of a resource until it depletes violates the way resources actually are exploited. Namely, as the more plentiful deposits are consumed, it becomes more and more expensive to get at the remainder, and that incentivizes economies to develop more efficient ways to extract the resources that remain, to conserve existing resources, or to switch to some substitute. Long before a resource is exhausted, the world typically does find a substitute. to quote Jesse Ausubel. The reason the world switched from wood to coal at the advent of the industrial revolution is not that we ran out of wood, just like the reason we switched from coal to oil is not because we ran out of coal. It’s because the new resources turned out to be more efficient with fewer negative side effects than the older one.

SV: In “Safety” you explain that we are safer in basically every aspect of life: in the workplace, from natural disasters, from homicide, etc. Gun control and safety is at the forefront of political discussions given the recent events in Florida. You briefly state “neither right-to-carry laws favored by the right, nor bans and restrictions favored by the left, have been shown to make much difference.” Do you have any further thoughts regarding gun control?

SP: I’m in favor of tightening gun control. It should be regulated like any other kind of dangerous technology, the way we regulate cars. The interpretation of the Second Amendment which nullifies controlling guns like we control cars is erroneous. It’s a tragic mistake the Supreme Court upheld that interpretation. I think it’s unlikely stricter gun control would make much of a difference in homicide rate, though. There might be fewer mass shootings, but there are so many guns already out there. The U.S. has such a well-developed culture of retaliation, intolerance of insults, and “culture of honor,” as anthropologists call it, that whatever the number guns we do have, we’re still going to have a higher rate of violence than other European countries. I do think these regulations are worth implementing and I think we need to acquire more knowledge about the effects of gun restrictions. The acquisition of such knowledge has been impeded by an absurd gag order on the Centers for Disease Control which prevents studies on gun violence. Being ignorant is always worse than being knowledgeable, and the policy of not studying something is always the worst conceivable policy.

AV: A common argument is with the increase of automation and A.I.s, there will be fewer jobs for humans. Can you explain your thoughts on this sentiment? Could there ever be a second Luddite revolution? Do you have any thoughts on universal basic income?

SP: I don’t have a confident expectation with what will happen with growth of AI or automation. On one hand they will clearly eliminate many jobs, but that doesn’t necessarily imply new jobs won’t materialize to put idle hands to work. Every challenge for robots has turned out to be much harder than we originally anticipated. We don’t even have cars that are allowed to drive automatically from point to point; there is some skepticism as to whether we’re going to see them any time soon. We may have trucks and cars that can change lanes, slow down or speed up on the highway, but we will still put a human behind the wheel to get it to the last couple of miles to the loading dock. Driving is a relatively easy challenge compared to ones that require a lot of tactile feedback, such as laying bricks, changing a diaper, or emptying a dishwasher. Even these tasks turn out to be harder than we thought. I’m skeptical of scenarios in which AI will revolutionize life because the problems AI have been set to solve are really hard problems, harder than one might think. I think this is a near consensus from people who are actually working in AI, at least ones I know. It may be as some jobs go the way of telephone switchboard operators or wheelwrights, the gains from automation could be redirected to other fields. We could perform more healthcare needs, hire teachers that instruct in the developing world over the Internet, or plant forests to suck CO2 out of the atmosphere. We just don’t know whether the economy will be supple enough to find new lines of work for the people that have been displaced from their old lines of work. Indeed, in the stats thus far, there hasn’t been the leap in productivity unemployment one might expect from rapid advances in AI or automation.

We also know that economies can expand employment opportunities in response to the supply of workers. This is what happened in the 1970s when massive numbers of women entered the workforce. Each woman that received a job did not necessarily take a job from a man; rather, the total number of jobs increased. For all we know this could happen again. If not, and if there is widespread unemployment or underemployment, it might increase pressure to adopt a UBI (Universal Basic Income) or at least a negative income tax. We already have one, the income tax credit, but it could be expanded to discourage Luddites. It would allow the economy to adapt dynamically to opportunities made available by technology and not be dragged backward by Luddites. That alone might be a reason to encourage that kind of income transfer, so the entire society can benefit from the obvious gains in productivity that AI promises, even if it hasn’t delivered it so far. Many of the jobs rendered obsolete by robots aren’t particularly desirable jobs anyway. It’s kind of perverse to romanticize the job of a coal miner, or a forklift operator, or a truck driver—professions that not so long ago were the subject of woe and pity and concern.

AV: Since people are living longer, what impact do you think this will have on our health regulations and the possible legalization of euthanasia?

SP: It’s possible that the ability of medical technology to keep people alive in a state that isn’t worth living, that is in pain or disability, could increase pressure for physician assisted suicide. I personally think this would be a tremendously humane development, assuming it came with obvious safeguards so you don’t have daughters-in-law wanting to do in their mother-in-law to accelerate their inheritance. States and countries that have adopted physician-assisted suicide, as far as I know, don’t have an epidemic of sons and daughters-in-law knocking off granny.

AV: In Enlightenment Now, you state C. P. Snow “never held the lunatic position that power should be transferred to the culture of scientists.” Why not? Wouldn’t it be interesting to see what scientists, engineers, and humanists could achieve if they were appointed to positions in the Cabinet to the President?

SP: I certainly think individual scientists who develop the expertise to run for office deserve our support, and I personally support a number of them. Not least to change some of the culture of the legislative process from the one that is second nature to lawyers, where the goal is to win, and replace it with one that is second nature to scientists, where the goal is to seek the truth. These are very different objectives in debate, and I don’t think we’re very well served by the lawyerly one. What I was referring to is the fear among many intellectuals that C. P Snow’s arguments and my arguments that suggest we should all think more scientifically is just a power competition among the elites. I certainly don’t think just because someone is a scientist that their positions on all issues should be taken seriously. I list a number of crackpot opinions that are often popular among scientists—not scientists that actually have the discipline and knowledge to run for legislative office. For example: we should have mandatory licensing for parents who screw up their children and harm society; we should seek the ability to colonize other planets in case we foul the earth so much that it’s unfit for human habitation, or the only way to prevent war is through a world government, or the only way to eliminate poverty and hunger in the developing world is to let them die of hunger or disease. I’ve heard all of these ideas from scientists now and again, and they’re all cockamamie ideas that should not be indulged just because they’re from scientists in some other field.

AV: They wouldn’t necessarily have to run for office, but they could be appointed, so you wouldn’t have people like Ben Carson saying things like the worse thing since slavery is Obamacare.

SP: On the other hand, he’s a neurosurgeon. I agree scientists who engage with the political process would be both an asset to the Cabinet or to Congress. I think a better example might be the contrast between Rick Perry as the Secretary of Energy, who is an utter ignoramus and buffoon compared to Ernest Moniz or Stephen Chu. It’s heartbreaking.

AV: Since the time of Freud psychology has become an influential science, and it really seemed to take-off in the 1960s. Its popularity with the masses may have tapered off, but there are expanding fields of psychology led by yourself and others such as your sister Susan Pinker, Jordan Peterson, Geoffrey Miller, and perhaps Gad Saad might also be included. What is your opinion about the importance of psychology in the world we live in today?

SP: I think psychology is tremendously important as a reminder of our limitations, our biases, our fallacies, and our illusions. Here I would point to cognitive psychologists like Daniel Kahneman, Richard Thaler, Tali Sharote, my colleague Dan Gilbert, and Dan Ariely, who have brought into the public sphere an awareness of our cognitive limitations. We should not be so fooled by our intuitions and gut feelings. An awareness of our moralistic biases is highly relevant to discounting our own moral outrage and trying to put our ethics on a more defensible basis. Here I would point to people like Jonathan Height and Joshua Green—those are two examples, but similar to my discussion with scientists, it doesn’t mean we should trust everything psychologists say. Rather, the field of psychological research should be integrated into our understanding of politics, persuasion and behavior change, and the judicial system so that our best understanding of us as humans is brought to bear on the desire of our institutions. I have to add this is an idea that very much came out of the Enlightenment—that there could be a science of human nature and that it should inform the design of our institutions. That was at the forefront of the design of the American democracy, in The Federalist Papers and in comments by John Adams, Benjamin Franklin, and Thomas Paine. They all alluded to their own intuitive psychology and their observations of what makes us tick, in order to design instructions that would lead to greater well-being.

Click here to purchase this book

at your local independent bookstore

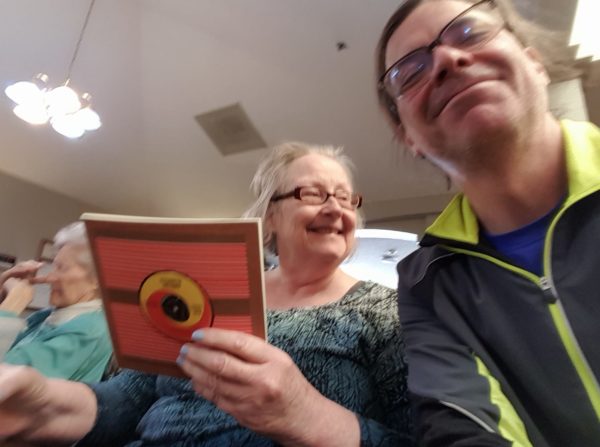

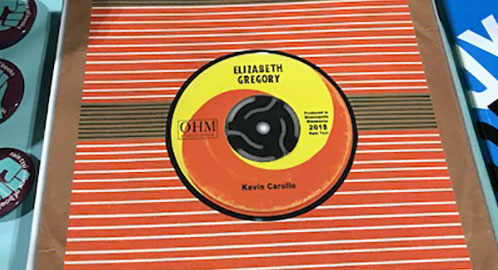

Kevin Carollo (pictured here with Elizabeth Gregory) is a poet and translator living in Fargo, ND. He is an Associate Professor at the University of Minnesota, Moorhead and editor for New Rivers Press. Kevin is known to birth cardboard critters and play guitar.

Kevin Carollo (pictured here with Elizabeth Gregory) is a poet and translator living in Fargo, ND. He is an Associate Professor at the University of Minnesota, Moorhead and editor for New Rivers Press. Kevin is known to birth cardboard critters and play guitar.

Yuta Uchida is a portraiture/figurative painter, born and raised in Hiroshima, Japan. After finishing high school, he moved to Superior, WI, where he found a passion for painting while he participated in several local art shows and exhibitions. He completed BFA in visual arts at University of Wisconsin-Superior.

Yuta Uchida is a portraiture/figurative painter, born and raised in Hiroshima, Japan. After finishing high school, he moved to Superior, WI, where he found a passion for painting while he participated in several local art shows and exhibitions. He completed BFA in visual arts at University of Wisconsin-Superior.