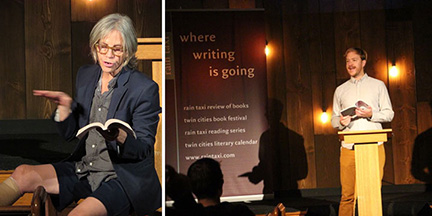

Dobby Gibson

Open Book, January 9, 2009

It was standing room only at the book launch celebration of local poet Dobby Gibson's second collection of poems Skirmish. Nearly 200 people gathered this chilly winter evening to hear Gibson read these finely crafted poems and then receive original fortunes written by Gibson at the reception afterwards.

Dan Beachy-Quick

Open Book, January 30, 2009

At this special event held in the Minnesota Center for Book Arts gallery, Dan Beachy-Quick read from his genre-bending book A Whaler's Dictionary, prodding the audience to dictate the course of metaphysical definitions inspired by Melville's Moby-Dick. Afterwards, everyone enjoyed a hearty rum punch and hardtack crackers!

Multiples Mall and Chapbook Lecture

Walker Art Center, February 21, 2009

The very first book fair at the Walker Art Center was a grand success! Minnesota artists who make book-related multiples set up shop for a day of merriment, complete with short presentations on the history of chapbooks, radical reasons for making multiples, and more. Also, Eric Lorberer presented a slide show lecture on the History of the Chapbook. View the lecture now at the Walker Channel.

C.A. Conrad, Aaron Kunin, and Magdalena Zurawski

Magers & Quinn Booksellers, March 8, 2009

In celebration of Small Press Month, three talented and entertaining authors read from recent works: Aaron Kunin read from his novel The Mandarin (Fence Books), C.A. Conrad read poetry from a variety of new and upcoming books including advanced ELVIS course (Soft Skull Press, 2009) and The Book of Frank (Chax Press, 2009), and Magdalena Zurawski read from her novel The Bruise (FC2).

FREE VERSE: The Collaborative Artists' Book

featuring Bill Berkson, Vincent Katz, and Lewis Warsh

Walker Art Center, April 16th, 2009

In conjunction with the Walker exhibition Text/Messages: Books by Artists, Berkson, Katz, and Warsh read and presented images from their collaborations with artists. Afterwards, they were joined by Eric Lorberer for a lively discussion on the process of collaboration. Vincent Katz read from his book Judge, a collaboration with Wayne Gonzalez as well as Alcuni Telefonini, a collaboration with Francesco Clemente; Lewis Warsh read his work Debtor's Prison, a collaboration with video artist Julie Harrison;, and Bill Berkson read from his work, Gloria, a collaboration with Alex Katz. You can view this event here.

Joanna Rawson & John Koethe

Common Good Books, September 11, 2009

In the acoustically-optimal depths of Blair House, Rain Taxi kicked off a new season with an intense double-header poetry reading. John Koethe read from his new book of poems, Ninety-Fifth Street, including the meditational and evocative title poem. Joanna Rawson read from her second volume of poems, Unrest, dark, challenging poems on this eighth anniversary of 9/11.

Kate Greenstreet & Norma Cole

Micawber’s Books, Tuesday, September 29, 7:30 pm

Those brave enough to face the gauntlet of traffic and highway construction were very lucky to catch this wonderful reading by Norma Cole and Kate Greenstreet. Kate read from her recent publication, The Last Four Things, and Norma read from her recent selected, Where Shadows Will: Selected Poems 1988-2008, along with new poems.

2009 Twin Cities Book Festival

Saturday, October 2009

Special guest authors for this one-day celebration of the written word included Diane Ackerman, Lorrie Moore, Nicholson Baker, Robert Olen Butler, Christian Bök, Adam Zagajewski, David Allen Sibley, Gabrielle Bell, and Ethan Gilsdorf. Click here to see more of the highlights from this great celebration of the book!

Dara Wier & Ed Sanders

Rogue Buddha Gallery, Wednesday, October 28, 7:30 pm

Poetry enthusiasts packed the gallery for this powerful, synergistic reading by two outstanding poets. Dara Wier and Ed Sanders, each employing a mesmerizing musicality, read from their respective (and newly released) Selected Poems to a wowed audience.

FREE VERSE: DIGITAL POETRY with Oni Buchanan & Brian Kim Stefans

Walker Art Center, Thursday, November 12, 2009, 7:00 pm

The audience was treated to a unique presentation of poetry in motion. Buchanan read from her organic and moving The Mandrake Vehicles, while Stefans beguiled with entropic fonts and Lovecraftian fish. See a video of this event HERE

Mickey Leigh & Legs McNeil

Nick and Eddie Restaurant, Friday, December 18, 9:00 pm

Punk rock fans got a glimpse of a legend's past as Joey Ramone's brother Mickey Leigh and "Please Kill Me" author Legs McNeil read from their collaborative new book, I Slept With Joey Ramone. After the reading, Mickey and a trio of Twin Cities rock musicians played a few Ramones tunes onstage! (Co-sponsored by Nick and Eddie.)

The international master of sound poetry Jaap Blonk wowed the crowd with his breath and breadth of talent, performing classic Dada sound poems by Kurt Schwitters and Raoul Hausmann, along with contemporary masterpieces by John Cage, including 4'33", and his own work on Cheek Synthesizer! If you missed it,

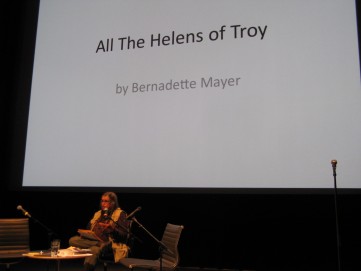

The international master of sound poetry Jaap Blonk wowed the crowd with his breath and breadth of talent, performing classic Dada sound poems by Kurt Schwitters and Raoul Hausmann, along with contemporary masterpieces by John Cage, including 4'33", and his own work on Cheek Synthesizer! If you missed it,  A wonderful reading from avant garde writer Bernadette Mayer who treated the audience to her new work The Helens of Troy, NY accompanied with a slide show of said Helens from Troy, NY. Then, along with poets Philip Good and Jennifer Karmin, proceeded to present poetry in a round-robin fashion. The audience was treated to the humorous yet deep "Untitled" poems of Good and the art-and-socially infused works of Karmin, including the Human Micropoem and a selection from Aaaaaaaaaaalice, complete with volunteers from the audience. All culminated with a collision of words as they read a poem about the higgs bosin particle! If you missed it,

A wonderful reading from avant garde writer Bernadette Mayer who treated the audience to her new work The Helens of Troy, NY accompanied with a slide show of said Helens from Troy, NY. Then, along with poets Philip Good and Jennifer Karmin, proceeded to present poetry in a round-robin fashion. The audience was treated to the humorous yet deep "Untitled" poems of Good and the art-and-socially infused works of Karmin, including the Human Micropoem and a selection from Aaaaaaaaaaalice, complete with volunteers from the audience. All culminated with a collision of words as they read a poem about the higgs bosin particle! If you missed it,  An amazing night at the Walker Art Center for the release of Dessa's poetry chapbook A Pound of Steam, published by Rain Taxi. A sold-out crowd was treated not only to Dessa's reading of the poems, but also to commissioned musical interpretations by three of her musical comrades—Aby Wolf, Sims of Doomtree, and Benjamin Burwell and Jake Pavic of Taj Raj. Afterwards the crowd gathered for a booksigning and reception, including a cocktail inspired by one of Dessa's poems, "The Bullet Rosette."

An amazing night at the Walker Art Center for the release of Dessa's poetry chapbook A Pound of Steam, published by Rain Taxi. A sold-out crowd was treated not only to Dessa's reading of the poems, but also to commissioned musical interpretations by three of her musical comrades—Aby Wolf, Sims of Doomtree, and Benjamin Burwell and Jake Pavic of Taj Raj. Afterwards the crowd gathered for a booksigning and reception, including a cocktail inspired by one of Dessa's poems, "The Bullet Rosette."

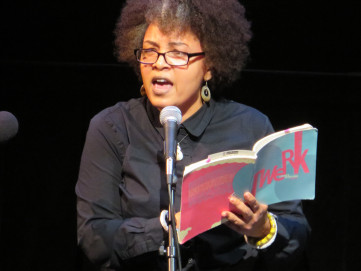

Nevada Diggs flexed her linguistic muscles with hypnotic musicality, humor, and verve, reading from her astounding book TwERK. Tapping into Michael Jackson's dance moves, animé, birdsong, and more, Nevada Diggs took the audience on a cultural ride through language and sound, race and ritual. If you missed this extraordinary experience,

Nevada Diggs flexed her linguistic muscles with hypnotic musicality, humor, and verve, reading from her astounding book TwERK. Tapping into Michael Jackson's dance moves, animé, birdsong, and more, Nevada Diggs took the audience on a cultural ride through language and sound, race and ritual. If you missed this extraordinary experience,  Beat legend Michael McClure roared in May with a mighty reading from his recent books, including the GAHRRRREAAAT Ghost Tantras, "BE NOT SUGAR BUT BE LOVE"—along with beautiful love poems to his wife Amy, a poem dedicated to Ray Manzarek and much more.

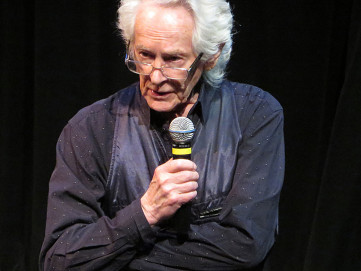

Beat legend Michael McClure roared in May with a mighty reading from his recent books, including the GAHRRRREAAAT Ghost Tantras, "BE NOT SUGAR BUT BE LOVE"—along with beautiful love poems to his wife Amy, a poem dedicated to Ray Manzarek and much more.

Some of the Twin Cities’ meowiest writers took the mic to unleash their cat poems in celebration of the third annual Internet Cat Video Festival.

Some of the Twin Cities’ meowiest writers took the mic to unleash their cat poems in celebration of the third annual Internet Cat Video Festival. Danish American Center, September 23

Danish American Center, September 23 Rondo Library, October 19

Rondo Library, October 19 Patrick's Cabaret, November 7

Patrick's Cabaret, November 7

Walker Art Center, November 20

Walker Art Center, November 20

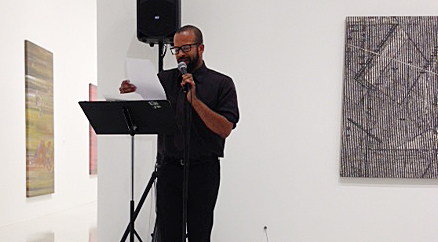

In this unique in-gallery program, poet Douglas Kearney, musicians Davu Seru and Pat O’Keefe, and dancer Deja Stowers responded to the paintings of Jack Whitten through dance, music, and poetry.

In this unique in-gallery program, poet Douglas Kearney, musicians Davu Seru and Pat O’Keefe, and dancer Deja Stowers responded to the paintings of Jack Whitten through dance, music, and poetry.

Blanchfield was joined by Minneapolis poets Juliet Patterson and Paula Cisewski, also both poets who are working on autobiographical prose books, for a conversation moderated by Rain Taxi editor Eric Lorberer and peppered with readings from their works. After the event the crowd enjoyed crostini during the book signing, and a splendid time was had by all.

Blanchfield was joined by Minneapolis poets Juliet Patterson and Paula Cisewski, also both poets who are working on autobiographical prose books, for a conversation moderated by Rain Taxi editor Eric Lorberer and peppered with readings from their works. After the event the crowd enjoyed crostini during the book signing, and a splendid time was had by all.

A lively and moving reading by poet great Laure-Anne Bosselaar wowed the audience at Plymouth Congregational Church. Bosselaar read from new and past work, as well as a poem by her late husband Kurt Brown.

A lively and moving reading by poet great Laure-Anne Bosselaar wowed the audience at Plymouth Congregational Church. Bosselaar read from new and past work, as well as a poem by her late husband Kurt Brown.

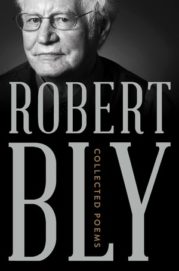

Bly’s Collected Poems was published in December by W.W. Norton and rapturously reviewed in the New York Times. The celebration will open with remarks by Bly’s biographer, Mark Gustafson, followed by favorite Bly poems read by family, friends, and representatives of the literary ecosystem Bly inspired and helped build over the past 60 years* A special guest is William Duffy, co-founder with Bly of the magazine The Fifties. Music will be provided by Zachary Cohen, principal bassist of the St. Paul Chamber Orchestra. A commemorative broadside printed by Gaylord Schanilec, the iconic Bly poem “Keeping Our Small Boat Afloat,” will be for sale at the reception following the program, and books will be available for purchase from Birchbark Books.

Bly’s Collected Poems was published in December by W.W. Norton and rapturously reviewed in the New York Times. The celebration will open with remarks by Bly’s biographer, Mark Gustafson, followed by favorite Bly poems read by family, friends, and representatives of the literary ecosystem Bly inspired and helped build over the past 60 years* A special guest is William Duffy, co-founder with Bly of the magazine The Fifties. Music will be provided by Zachary Cohen, principal bassist of the St. Paul Chamber Orchestra. A commemorative broadside printed by Gaylord Schanilec, the iconic Bly poem “Keeping Our Small Boat Afloat,” will be for sale at the reception following the program, and books will be available for purchase from Birchbark Books.