Interviewed by Scott F. Parker

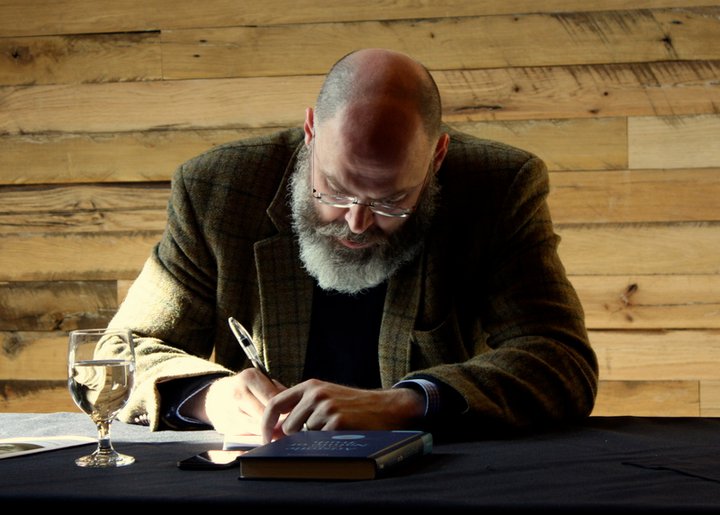

John T. Lysaker is a professor of philosophy at Emory University and the author of several books, including the recently published Philosophy, Writing, and the Character of Thought (University of Chicago Press, $35) and Brian Eno’s Ambient 1: Music for Airports (Oxford University Press, $14.95). I met John when I was a student and he was teaching 19th-Century Philosophy at the University of Oregon. As an unruly junior, I had blown off the first week of the term to take a long spring break visiting friends in the Midwest, but I regretted my brazenness severely as I came to appreciate what a committed and caring and good teacher John was. Eventually I got enough credits to graduate and left Eugene, but I kept reading John’s books, which run counter to much of what most people find frustrating about academic writing. John’s writing is scholarly, to be sure, but never merely so; he takes philosophy as we all should—personally. His prose is full of personality, wit, self-awareness, even self-doubt, and always good will. When I learned that philosophy writing was to be the subject of his new book, I sent him an email. The following interview should make clear why I’m glad I did.

Scott F. Parker: Let’s start right at the beginning. Tell me about your use of “character” in the title. A reader might expect “nature” there. But character has important implications for you, right?

John Lysaker: Let me start by thanking you for the opportunity to discuss the book, and for your thoughtful questions. Nature is apropos, but it lacks some of the resonances that character provides. Like nature (or essence), character names something like a general way of becoming or living, as in someone’s character as opposed to a passing reaction. I am interested in the character of philosophical thought, how it comes to pass, how it relates to others, and how it engages various historical situations. And a central claim is that different genres and logical-rhetorical operations influence that character, which is why we ought to be concerned with them. But a second sense also operates, that of dramatic character. I think the character of one’s writing stages or enacts philosophy, and in fairly definite scenes: voice, those cited and ignored, how those cited are engaged—carefully? generously? polemically? I think many are comfortable with reading Socrates as a character of philosophy. But the genre of the dialogue is also a way of characterizing philosophy, of exemplifying it. It suggests: philosophy comes to be in discussion. And if that flies, I think we should read other philosophical texts as staging something similar. Aristotle suggests that a tragedy is an image of an action (or two). The whole play presents an action in its dynamic unfolding. I now approach philosophical texts as images of acts of philosophy, and I wanted to write a book that imaged the character of philosophy in a very definite way even as it made that issue its principal, thematic concern.

John Lysaker: Let me start by thanking you for the opportunity to discuss the book, and for your thoughtful questions. Nature is apropos, but it lacks some of the resonances that character provides. Like nature (or essence), character names something like a general way of becoming or living, as in someone’s character as opposed to a passing reaction. I am interested in the character of philosophical thought, how it comes to pass, how it relates to others, and how it engages various historical situations. And a central claim is that different genres and logical-rhetorical operations influence that character, which is why we ought to be concerned with them. But a second sense also operates, that of dramatic character. I think the character of one’s writing stages or enacts philosophy, and in fairly definite scenes: voice, those cited and ignored, how those cited are engaged—carefully? generously? polemically? I think many are comfortable with reading Socrates as a character of philosophy. But the genre of the dialogue is also a way of characterizing philosophy, of exemplifying it. It suggests: philosophy comes to be in discussion. And if that flies, I think we should read other philosophical texts as staging something similar. Aristotle suggests that a tragedy is an image of an action (or two). The whole play presents an action in its dynamic unfolding. I now approach philosophical texts as images of acts of philosophy, and I wanted to write a book that imaged the character of philosophy in a very definite way even as it made that issue its principal, thematic concern.

SP: You offer The Republic as “a philosophical and literary masterpiece . . . with such a degree of integration that [it] resists the opposition.” Is that opposition typically methodological? How do you distinguish between philosophy and literature? Or how do you understand the relationship between them?

JL: This is a thorny question, and I can imagine a long road and shorter one, though neither would end satisfactorily. The longer one would return to the last essay in After Emerson, where I imagine different ways of receiving a thought, organizing it, and addressing it to another. Using that schema now, I would say that at each pivot, philosophy, poetry, the novel, the short story, and so on have a different character, and some could be better described as literary, others philosophical. Critique is a quintessentially philosophical way to receive concepts. One tries to locate their origin and determine the rules that govern their use. The lyric poet does not interrogate the muse. Emerson’s address favors provocation at the expense of demonstration, and that renders him more a poet in prose (his words) than a philosopher, at least at various points. And so on, working from paradigmatic examples. But that is a long road, and there will be exceptions at every turn.

The shorter road lies with thinking about how a text organizes whatever it offers readers. In the remark you quote, I have in mind how The Republic is a rhetorical whole whose parts relate to one another in modes other than the elenchus Socrates directs toward Cephalus and Polemarchus in Book One. But those other modes, and not just the allegory of the cave, but also the ways in which the dialogue discusses and enacts the making of a city in speech, or how the account of acceptable narratives in Book Three frames the Myth of Er in Book Ten, seem integral to the overall goals of The Republic. And so, at the outset, I am willing to call the elenchus or the theory of the soul in Book Four philosophical because of their explicit theoretical and inferential character and the other modes “literary” for their lyric trust and indirection. But I also want to take back that distinction at a later point because, at least in the context I’ve assembled, “literature” is such a loose and unhelpful term. It smashes together too many different genres and logical-rhetorical operations. Moreover, many hear “literature” and think it gives them a kind of license, and that is precisely not what I have in mind. The book is thus working through the philosophy-literature distinction from a standpoint of dissatisfaction, both for the distinction it seems to make and for all that it fails to distinguish. But, it—the distinction—is a way to get the ball rolling, so I provisionally employed it at the outset and chose to employ it in order to remind us that The Republic, a text at the heart of the philosophical cannon, relies on inferential demonstration and evidences extraordinary literary ambition, meaning it expects readers to pay attention to more than its thematic content and scenes of linear argumentation.

SP: More and more I’ve found myself thinking of philosophy as a branch of literature. I read its concerns as common with poetry, fiction, essay: what does it and what could it mean to be human? What varies are the conventions one follows, and who are the authors one responds to and is influenced by. But, then, as your book reminds us, philosophy is not a form of writing but perhaps a cluster of concerns that can inhabit all sorts of forms (the journal and the treatise, but also the poem, the story, the essay). Even so, I want to see philosophy as an aspect of that larger project of interrogating humanness.

JL: But art too, no? Isn’t that project shared across the humanities? To interrogate and disclose humanness, one moment curling back into the other? Philosophy remains the most radical form of interrogation I’ve found, but we are, fundamentally, beings of response, only one of which is interrogation, which leaves philosophy haunted by moments for which it cannot fully account. Moreover, philosophy is neither the only nor the most powerful mode of disclosure; that falls to . . . I’m not really sure. Different art forms run down different paths. (And this is why I am so inclined to run after them.) But when the interrogative mode (or mood, or manner) is let loose, I think we run into philosophy. And when we abandon ourselves to disclosure beyond what interrogation can secure, I think we run into art. Now various forms have settled near the end of both paths; critique in one pole, the lyric poem another. But Parmenides wrote a poem and meta-fiction has been around for long enough to leave us with a hybrid typography. Moreover, one text can do both. In fact, since the onset of the 19th century if not well before, both moments have been operative in high water marks of philosophy and art. I suppose that is why I now think of myself as a humanist before any other designation. I’m committed to the conversation, to interrogation and disclosure, and no one discipline or practice can carry that burden on its lonesome.

SP: Can you talk about your interest in literature as we usually understand the term. Your books are full of literary references. Your first book takes its title from Rilke and explores how poetry creates meaning. When you were at the University of Oregon you sometimes taught in the comparative literature department as well as in philosophy.

JL: I insist that we can learn from artworks, not just learn about them, and I have tried, at least since 1996, to write in such a way that I staged dialogues between philosophical and literary texts, particularly poems, and lyric poems at that. I keep turning to poems (occasionally paintings as well, and more recently Brian Eno’s ambient music) because they take me to thoughts that I would not have found otherwise, and I want to acknowledge the discoveries and the kind of discoveries that have propelled my thought. More generally, I have always resisted a complete embrace of Kant’s critical project and opted instead to allow myself to be claimed by what seems to be an insight and to follow its lead, testing it as I go, even essaying it, rather than, ahead of time, trying to secure safe passage for its operations and commitments. And this involves embracing a kind of lyric event at the deepest level of one’s thought, which leads to an unusual experience. One finds oneself less the author of one’s thoughts than claimed by them. This can be taken in a general way, of course, but in my case, poems have often been quite generative. For example, a somewhat recent piece, “In the Interest of Art,” travels a good distance with Adrienne Rich’s poem “Tattered Kaddish” after a shorter trip with Auden. And something I’m working on just now, an extended meditation on hope, is moved at various points by particular poems from Lucille Clifton, Anne Sexton, and Terrance Hayes, and Hayes helps me think through the multifaceted whiteness of Wallace Stevens’s poetic imagination. And my next project, which concerns friendship, will throw in with several poems. Maybe I could say something general at this point: poems are not ornamental in my work—they co-constitute the kind of conversation my work aims to exemplify.

JL: I insist that we can learn from artworks, not just learn about them, and I have tried, at least since 1996, to write in such a way that I staged dialogues between philosophical and literary texts, particularly poems, and lyric poems at that. I keep turning to poems (occasionally paintings as well, and more recently Brian Eno’s ambient music) because they take me to thoughts that I would not have found otherwise, and I want to acknowledge the discoveries and the kind of discoveries that have propelled my thought. More generally, I have always resisted a complete embrace of Kant’s critical project and opted instead to allow myself to be claimed by what seems to be an insight and to follow its lead, testing it as I go, even essaying it, rather than, ahead of time, trying to secure safe passage for its operations and commitments. And this involves embracing a kind of lyric event at the deepest level of one’s thought, which leads to an unusual experience. One finds oneself less the author of one’s thoughts than claimed by them. This can be taken in a general way, of course, but in my case, poems have often been quite generative. For example, a somewhat recent piece, “In the Interest of Art,” travels a good distance with Adrienne Rich’s poem “Tattered Kaddish” after a shorter trip with Auden. And something I’m working on just now, an extended meditation on hope, is moved at various points by particular poems from Lucille Clifton, Anne Sexton, and Terrance Hayes, and Hayes helps me think through the multifaceted whiteness of Wallace Stevens’s poetic imagination. And my next project, which concerns friendship, will throw in with several poems. Maybe I could say something general at this point: poems are not ornamental in my work—they co-constitute the kind of conversation my work aims to exemplify.

SP: How uncommon are attitudes and approaches like yours in philosophy today? And in addition to Hayes, who are some of the contemporary poets you’re into? I remember Simic was an important reference for you.

JL: Not too common but not unique, except in a narrow way, meaning, the book’s weave of the aphorism and essay, the aphor-essay perhaps, is mine. At the level of the sentence, Stanley Cavell opened a path for those who want to make words count above and beyond their grammatical position and definable intension (and intensity). John Stuhr’s recent Pragmatic Fashions (Indiana, 2016) offers essays in expressivist pragmatism that exemplify personal visions from various standpoints or what he terms “vistas,” stressing their situatedness (as opposed to simple subjectiveness). And John Kaag has experimented with philosophy through/as memoir, e.g., the recent Hiking with Nietzsche (FSG, 2018). (Maybe the banality of the name “John” drives one to act out?) Megan Craig has been writing essays that move in their own way, touching notes that are similar to mine, but her voice is so much her own that her pieces don’t remind me of anybody or anything else. I think too of Vincent Colapietro in this context, who is drawn to improvisation as a thematic focus and performative slant, though his solos are long form, punctuated by quotation.

Outside of academic philosophy “proper,” Fred Moten, poet and theorist, is on his own path, running down and against shorter lines of thought and expression. Black and Blur (Duke, 2017) is incredibly stimulating. But a generation ago, several French women were setting the bar, particularly Irigaray and Cixous. There have always been countercurrents, therefore, at least for those willing to swim. Regarding poets, I still swim in Wallace Stevens and some of his lines and thoughts have been integral to various essays, both by way of embrace and contestation. Simic was the subject of my first book, You Must Change Your Life, and he remains someone I read, both his new and old material, and there are traces of him in Philosophy, Writing, and the Character of Thought. Finally, Alice Notley’s Certain Magical Acts is also helping me think more about voice, and I just love the short lines in All We Saw, by Anne Michaels. Lyric concentration—it just draws me, in and thus out.

SP: You wrote somewhere that no one gets into philosophy because they want to write journal articles; they get into philosophy because they want to write like Nietzsche. While your writing has always demonstrated a literary sensibility, your books have moved increasingly in the direction of the personal and, by my reading, the ambitious (to draw a contrast with your characterization of most philosophy writing). You’re really going for it as a writer in this book, aren’t you? Do you feel freer writing in this style? Was this a fun book to write?

JL: It was a tricky book to write. I kept losing the life of it. At one point I thought, and this ended up in the book: what a mistake to write the book on the aphorism. But once it settled into its chapterless collusion of short essays, concentrated arguments, and the occasional aphorism (and all of the titles), it became fun to write, to worry about things that usually don’t come into play in professional articles such as rhythm, punch, just the right amount of learning on display. I often would prepare material for long discussions and keep condensing it until I had the roux just right. Or thought I did. I thus don’t know if it was or is freeing way to write. In a way, I find it an even more disciplined way to write. But I get what you mean and can answer affirmatively—writing this way has let me say things I couldn’t otherwise say. And those things do involve “really going for it,” the “it” being something Thoreau imagines for himself—a kind of writing that leaves rather than simply records an impression. Though this has always been a goal—to reach the thought of others where that thought lives, where they live. And to provide them with meaningful company in the selfsame place.

I suppose I also wanted to really write in English, not write in an English always looking over its shoulder toward German or Greek. Not in order to be “American” in some way, but to exemplify the labor of inhabiting a language with deep care, which is something Cavell’s writing impressed upon me. Also, a reading of Barthes’s A Lover’s Discourse helped me to see how an approach from many angles, and varied angles, might keep the complex objectivity of my subject matter front and center. I could go on. So many lines of influence, and so many possibilities other than Nietzsche, though his texts, particularly Beyond Good and Evil, remain near the heart of the project and of me. But I don’t want to hold Nietzsche up as the best alternative. I thus like your language of “go for it.” If you really went for it, how would you write? That is the question I’d like to press, and I suspect the character of each reply will unfold somewhat differently.

SP: Do you have any ambition to move farther in this direction? To write something that a reader might pick up and not immediately recognize as philosophy (with all the baggage that carries with it)?

JL: The current piece on hope may be like that, I don’t know. I sometimes think that a chunk of philosophers don’t consider what I do as philosophy whereas most non-philosophers do. I like to argue, to clarify and pass judgment in a considered and considerate manner, to employ “therefore” and, importantly, to have earned it. And I think it vital to stage examination in conversation, to show that one has learned and that one is still learning, and accounting for oneself along the way. If all that continues to characterize my writing, I think it inevitably tips my hand, particularly given that my learning, even in the company of poems, is still coursing through texts by Hegel, Beauvoir, and Aristotle, and with regard to very philosophical topics: the good life, justice, the nature of the self, etc. But I’m quite happy with that. I have never wanted to leave philosophy, only to find my own way into it and so better exemplify it.

SP: In thinking deliberately about how philosophy is written aren’t we led to bigger questions about what philosophy is and is for?

JL: Absolutely. In the book, I argue that once one begins to deliberate about one’s writing, the why clarifies the how. In fact, one can’t have a cogent how without a why. So again, absolutely, which is why I insist that writing is a praxis. Not that it should be; it is, even Kant’s Critique of Pure Reason. But there are many whys orienting the bearing of philosophical texts: truth, maybe just insight, personal transformation, social change, the refutation of another view, etc. I am thus less interested in settling the why of philosophy than in allowing one’s why, whatever it is, to organize the way in which one writes. (This is why the book’s beginning drones a bit with regard to “praxis”; a good deal hinges on making that turn.)

But hearing myself now, I sound coy, too neutral. A certain sense of ethics seems integral to philosophy, one that valorizes examination in the company of others, in conversation, as well as a politics that refuses to recognize authorities as genuine authorities if they do submit their rule to examination in conversation with those they govern. This is one thing (and only one thing) that is so troubling about the Trump Administration. Whether through silence, refusals to respond, or lies, the current president announces, with his conduct, “I am not answerable to the American people.” And this manner is only intensified by his tweets, which eschew all justification. From an ethical and political point of view—and I am always in that register—it is an outright shit show. No one remotely committed to the examined life can be heartened by it. But they might be called to intensify their own commitment to and enactment of it.

SP: I think it was during the W. years that you said in an interview that the U.S. is a “stupid country.” In this book you say that many Americans would consider philosophy anti-American. And you write, “Our moment is thoughtless, even in those corners where genuine discoveries occur. How does one converse in a public where an anti-science stance is political capital and sound bites seem to satisfy the desire to know? Where everyone has their button words?” (138) Yes, how do we?

JL: I wish I hadn’t said that back then. (Or maybe I wish you hadn’t remembered it.) In many ways, the United States is inhabited by millions of incredibly talented, smart people. But that intelligence seems to diminish when it comes to the kind of questions that compel me, and when it comes time to deliberate about political matters. We love slogans and are driven by anecdotes, and that doesn’t even include people who believe utterly fantastic things, such as with Pizzagate, which alleged that Hilary Clinton and Nancy Pelosi helped run a child sex ring out of a D.C. pizza parlor. That’s just bat shit crazy, and if one lets it drift into allegory, despair ensues. But that’s not the whole or even the largest part of the nation, so I now regret my earlier generalization. I should have been less arrogant and more nuanced.

Concerning the line from my book, the weight of the thought falls on “converse,” with the threat marked as “button words,” calling to mind having one’s buttons pushed as well as sloganeering as a mode of faux interaction. As a teacher, I have ways of slowing down and so empowering the conversation, which is key, I think, as is stressing the larger task at hand: finding the most compelling position as opposed to winning or losing arguments. So we ask: what are we actually saying? What reasons can we offer on its behalf? What reasons are offered on behalf of contrary and contradictory positions. What are the strengths and weaknesses of the more common positions? Are there other, less common positions we might consider or imagine?

But of course, I can’t and shouldn’t turn public discussion into a teacher-student relation. That’s a philosopher-king pose (or character), and that runs counter to the kind of positioning I champion in Du Bois’s Souls of Black Folk and Benjamin’s One-Way Street. So the question becomes—how can we slow down the exchanges that seem to push so many buttons, and can we cultivate the ability to view conversation as a practice of joint discovery and transformation? I think hosting exponentially more public conversations in K – 12 schools, libraries, bars, and coffee shops would open one route. And to do that, we would need to pry academics from the genre of the editorial and opinion piece, which is too close to the pulpit for my taste. I also believe that introducing philosophy into the K ¬– 12 curriculum would be wildly transformative and help establish certain habits of and capacities for reflection and dialogue. (Philosophy for Children is a movement with just these ends in mind.)

Of course, neither of those proposals valorize writing, and for broad scale change I think writing comes too late. Not that one can therefore quit the game when one writes, that is, the game of impacting the deliberative capacities and habits of one’s readers. But one should write with a sense of the weakness of one’s efforts. (I take the term from the philosopher and artist Megan Craig, who inherits it from Gianni Vattimo, I believe.) In this context, acknowledging weakness means acknowledging much of what underwrites author-reader relations, including learning, energy, and time. It also means recognizing that writing, philosophy, these are two-way streets. They offer possibilities to as well as operate on readers, and so they leave a great deal up to readers.

That said, weak thought is not powerless; one always has one’s example and the non-coercive force (or moral charisma) it wields, which brings us back to the character of thought. Each bit of writing, by way of tone, citation, quotation, example, etc., signals to readers a path of interaction. I find the polemic so troubling because it engages in order to wage war, and often in a total way. Similarly, I am troubled by texts that do not quote or quote poorly. They exemplify a kind of narcissism that undermines transformative conversations. And then there is disagreement; is it even imagined, staged in generative ways, or encouraged? What does writing do before push comes to shove? Such moments are telling and possible scenes of provocation, even instruction through exemplification. But thinkers of all sorts should spend more time in the community, and not in the role of the “expert.”

Universities, which present themselves as producers of knowledge, are inclined to favor public scholarship that better distributes the knowledge it produces. That model, a technical one (in a technical sense), serves philosophy poorly. Also, there are just too many talking heads. Rather than pour more “content” into the quickening circulation of purported facts, opinions, and histrionic performances, let’s find ways to slow cognition down, and to cultivate a capacity to face cognitive dissonance, endure it, and respond creatively.

SP: Early in the book, you write, “What is in doubt, however, is what I choose when I commit to a manner of writing.” Let’s talk about the form you use: short chapters comprising short (sometimes only a sentence) essays and occasional aphorisms, each with its own bolded title—I thought of Nietzsche first. You were greatly influenced by Benjamin’s One-Way Street. What considerations were you taking into account as you committed to this form?

JL: I committed to the form over time, so I more found my way into it then established it whole cloth. The form emerged because I wanted to preserve for the reader the intensity that the thoughts had in their occurrence and to acknowledge that my topic, writing philosophy (or just philosophy, and then, as we just saw, the examined life more generally) will not be found in a single form, manner, or bearing. Irony required a longer discussion, but some thoughts resonated best as aphorisms. And I needed to find a non-polemical way to take the polemic to task, and that required a more careful reading of a particular case. But not only subject matter determined the length. I often thought—who would still be reading after this many pages? And I mean genuinely reading, not skimming for the basic point. (In my first book, I spent about fifteen pages on a very short poem. Cool, I thought. Not so cool, I later heard.) I thus wanted to write in a way that not only held but also stimulated attention and might be worthy of rumination. But I wasn’t sure I had even managed the half of it (and I’m still not).

So, for the first time, I sent the book to two friends before submitting it for review: Michael Sullivan, my colleague at Emory, and Rick Lee, who teaches at De Paul. At a few points, Rick said: I could really use a few punctuated, incisive remarks here. And so I added them. As you can see, then, I followed my own deliberative model while writing the book. That is, the form reflects concern for how my thought might unfold, the kind of relations it establishes with readers, and how it might resound in the present. Concerning the latter, I wanted some discussions to employ sophisticated scholarship and to evidence careful reading because I find contemporary American life hostile to theory and reflection more generally. (Hence footnotes as well. Insight can flow from learning and should flow back into it.)

All that said, I also had examples, and Benjamin’s One-Way Street was certainly one, and a central one. It combines so many ways of objectifying thought, and it was while writing an article on One-Way Street that the idea for the book came to me, although I elected to omit dreams, which Benjamin records. Not because I object to his use of them, however. Rather, dreams simply have not been a generative part of my thought process (even after reading Michel Leiris, whose dream-record was more than worth my time).

SP: I don’t know of many philosophy books that situate themselves quite like your does. You’re not writing for a popular audience in a way that this book will likely end up in a lot of bookstores. But neither are you writing only for other professional philosophers. Some of your chapter titles—“Message in a Bottle,” “The Secret Addressee,” “Unknown Friends”—give a sense of who your audience might be. I read the book as an opening gesture in a mutual exchange between friends. There’s this heartfelt concern for your readers on the page and this trust that they are up to the task of doing philosophy with you. It’s frankly unusual for philosophy. I take it you’re following Emerson in this, that you’d rather provoke or entice than simply explain.

JL: I love this: “There’s this heartfelt concern for your readers on the page and this trust that they are up to the task of doing philosophy with you.” Thank you. I have always sought a kind of intimacy in my voice, in part because I hope to intimately address the reader, as I suggested above. And this requires a certain kind of vulnerability and trust on both sides. And as you note, this operates in Emerson, and Nietzsche too, which may be his biggest debt to Emerson, the intimacy of his address. I suppose this is also my way of saying: I’m not fucking around here and I expect the same from you. And that is very much a mode of provocation. But I stop short of Emerson’s de facto insistence on provocation over demonstration. I still embrace the latter, but not in a manner that tries to exhaustively address an issue, as if one were writing for the last word. I’m not, which is why I am so drawn to the image of the friend in your remark, and to Emerson’s sense that he writes for unknown friends. But I am offering them views and defenses for them.

I recently had the luxury of a scholarly session devoted to After Emerson, whose last chapter, “Emerson and the Case of Philosophy” I wrote as a passageway into Philosophy, Writing, and the Character of Thought (which was already underway). Because After Emerson is a book of essays, I had that form in mind, but the overall sensibility, which I inherited from Cavell, carried over into this book, and I hope to maintain it in future books. I have committed to a philosophy that aims at a certain kind of representativeness without assuming that it is representative, and without taking itself, once and for all, to have proven its representativeness, even after it says its piece. Such a philosophy thus commits in a manner that awaits a reply. It thus strives to render itself legible and plausible, even compelling. But it does not purport to speak for any and all rational agents, or even for some “those in the know.” It is provisional, but not just in a fallibilistic sense; it also provides food for thought, language to be taken up into further experiments.

In short, and somewhat unlike Cavell, I’m happy to offer theories, make particular claims, and to keep elaborating and/or defending them if questions or objections arise, and I hope they will. I want academics to engage the book. But not just them. I also wrote it for anyone who has found themselves in the grip of a philosophical question or text, to offer them some company and to cajole them into joining the fray.

SP: How does the interview as a genre relate to your concerns in the book?

JL: As I’ve said, one of my goals was to articulate a determinate space for considering experiments in genre. How will thought unfold in this genre (which is a way of asking, how will this genre enable me to address the issue that has claimed me)? What relations will this establish with addressees? And how will this resound in the contexts in which texts and addressees meet? One might be drawn to interviews in the interest of accessibility, that is, broadening the range of one’s addressees. But depending on the interviewer (and the venue), one might not be invited to work into the heart of various issues. And that may reinforce worrisome cultural trends, such as an over fondness for the authoritative voice, sound bites, “the big picture”—as if it weren’t full of several smaller pictures, each a bit smudged. To be clear, I am thinking as a philosopher here, by which I mean, someone pursuing questions and claims about the good, justice, truth, the nature of art, knowledge and error, and the basic character of existence, human and otherwise.

But all that said, I am drawn to the fact that an interview involves two, and if the questions are thoughtful, as yours have been, they can prompt new formulations, even thoughts. And there have been interviews that I regard as primary texts. One of Foucault’s discussions with Deleuze, “Intellectuals and Power,” comes to mind. In English it appeared in Language, Counter-Memory, Practice (Cornell, 1980). Their discussion concerns the intellectual as a social category, and to my mind, it is essential reading, particularly in the context of Lenin, Luxemburg, Gramsci, and Mao, though I would also include “Theory, Pragmatisms, and Politics,” by Cornel West, which was collected in his Keeping Faith (Routledge, 1993). Regardless, the interview with Foucault and Deleuze, which is also a dialogue, is both rich and engaging and it has stayed with me far longer than many other more polished bits of prose. And it offers some interesting exemplifications as well—both are acting there as public intellectuals. Thinking about that interview now, I wonder whether interviews aren’t always enroute, at least to some degree, toward the dialogue, meaning, I could pose you questions and you could take issue with how I reply to what you’ve asked. Would that realize more fully the capabilities of the interview? (Christopher Long explored this through his podcast, Digital Dialogues.) If not, I want to think more about what interviews enable along the three lines I indicated. I very much like how your questions have brought me back into my project from various angles and reanimated various thoughts. But I can’t help feeling like I need to shut up and return the favor. I thus wonder how you see the interview, whether at the points I’ve marked, or in other terms?

SP: Now that you’ve turned this question around on me, I’m appreciating what a big category “interview” is. Let’s take the case at hand. Most of my questions would have to be scrapped or drastically revamped if we were here primarily to promote you and move product. So, venue matters greatly. As the interviewer, I’m trying to balance several interests: mine as a curious reader; yours as someone whose time I’ve asked for and would like not to waste; Rain Taxi’s so they will want to publish this without trimming excessively (surely we’re pushing Mr. Lorberer’s word limit pretty far here); and, ultimately, the readers’, whom I very much would like to hang onto until the end of the interview. More practically, I orient myself by asking what are my curiosities about you and your work that Rain Taxi readers are likely to share. So the genre is lined with constraints.

But you asked a general question: What opportunities does interview afford? One answer is personality. You might read a poetry collection and ask yourself what it would be like to talk to the author. Interview gives the impression of more direct access to the consciousness behind the text and that that access is more immediate and less artificial than what comes across in the written text. I’m suspicious of the idea that a real self emerges more in an interview than in, say, a novel, but I’m susceptible to the impression even as I consider one of my favorite interview subjects, Bob Dylan, who excels at frustrating the search for the self behind the text. We can easily imagine (or possibly name) writers for whom the interview is their best genre. But good interviews bypass the trap of personality and stand as a form of public conversation. There’s something exciting about watching someone think out loud. An interview is like an essay in its ability to dramatize that process. But unlike the essay there’s someone else provoking (hopefully) the subject’s thinking. And I think that kind of intersubjective space tends to be more alive for the audience than subjective space, and very often for the principals too.

JL: Interviews as public conversation, very much so. And I agree that interviews can offer a kind of spontaneity and personality that goes missing in a lot of writing, and then in an intersubjective space, which, while always operative, is often buried. Foucault gave many interviews, and many were incredibly illuminating. They show him thinking, which is why I am draw to them, as opposed to getting at the consciousness behind what one reads elsewhere. They are their own thing, like Emerson’s journals and letters, and I want to read them as such rather than as keys to other texts. With the interview, I think we find thinking in response, and that is my attraction to them, thought venturing replies that are willing to be more vulnerable than any book can be given how many times it has been revised, edited, etc. (Of course, this has been revised; it is a matter of degree.)

Having said that, I realize that some interviews occasion evasions rather than responses, particularly with artists. It thus dawns on me that philosophy slides into the interview rather easily whereas most artists are jumping ship when they agree to be interviewed. And I can appreciate their frustration if questions drift into: what did you mean here? That question misses how artworks mean, I think, as does the common reply: it means whatever my readers think it means. But I think questions about the social value of art, meaning in music, or the nature of creativity, etc. are fair game and worth considering. One might reply, “Those sound like philosophical questions.” They do because they are. But philosophy percolates wherever any practice begins to interrogate its ends and basic character, and most folk are led to those corners at some time or other. And that’s what I would want to hear from Dylan, or the painter Anselm Kiefer, or comedians like Maria Bamford and Amy Schumer. I think Schumer’s television show, by including interviews, exemplified comedy confronting its own reliance on types. And Bamford inhabits language and the lingua franca with such an exquisite sense that it seems akin to philosophy and poetry. I would want to know: what does your work ask of people? How do you take up other modes of expression? Are there other modes you admire? Why? Is the commodity a threat to what you do? But maybe that’s not the most productive tack. Can one interview an artist and let them remain an artist in their reply? I’m not sure. As you can see, I’m hopeless; philosophy has me.

SP: There’s this horrible phrase that’s used all the time now that says we “consume content.” People who use it are usually taken with computer metaphors. They think of hardware, software, and downloading information. As long as you have the information and/or argument, the means of acquisition are irrelevant. But even “acquisition” makes a lot of assumptions. You consider writing (and I think reading) praxis. What do we lose by treating writing and reading as information exchange?

JL: In some ways, I addressed this above, and my impatience with “it means whatever you think it means” begins to reply, but further specifications are necessary. First, casting texts into an economy of information exchange reduces everything to content, and in a way that treats it as separable from form (or form from content). And that just flat misses the performative dimensions of texts, which is a loss for readers and writers. No Plato. No Montaigne. No Hegel. No Emerson. No Du Bois. No Beauvoir. No Luce Irigiray. No thanks. The medium isn’t the only message or even separable from some message, stated or not; the medium or mode of presentation is very much integral to whatever a philosophical text has to offer. Even texts that aspire to limit themselves to inferential forms offer more than information: That Y follows from Z is not just another bit of information, it is principally a way of justifying Z. Patterns of justification are obscured when we treat everything as “information,” so a particular form seems to sneak in—the opinion—which from an inferential standpoint is just an assertion. And when only assertions abound, a more general social pattern operates: consumption. Here is some content. Use it or not, however you like. You have your opinions, I have mine. It’s a coward’s détente. But what if an author and reader meet in a place where we’re not sure how things should be used or to what end, or if they should be used, or what “use” even means? More generally, what if the question at hand concerns the origin and limits of the idea that we are first and foremost consumers? How is that conversation going to get off the ground if the scene of reading and writing is already bought and sold? In the book, I wave at this with an aphorism: “The marketplace of ideas—the metaphor’s success proves its bankruptcy.” Validity is not a popularity contest.

SP: I’m thinking of realists like Steven Pinker and Sam Harris. They seem to have such a hard time reading someone like Nietzsche who isn’t simply making claims about the way things are.

JL: Nietzsche is a particular conundrum because he interrogates the will to truth, finds untruth as a condition of life, and expects that finding to transform the will to truth from the inside. Telling the truth about truth transforms what we take “truth” to entail and what value we place upon it. I’m not sure authors like Pinker and Harris can digest that kind of thought, one that ventures claims about the way things are with regard to claims about the ways things are. But that is the way in which Nietzsche is an experimental writer, meaning, he sets in motion inherited operations whose result cannot be completely foreseen. These experiments neither verify nor falsify, however, but generate new thoughts, e.g. that the self might be a multiplicity of souls. Moreover, they do so within a new way of receiving and measuring the validity of such thoughts, namely in terms of their ranked value. Does that mean I don’t want to read Pinker or Harris? No. But I approach their texts from a different position than the one from which they were written.

SP: How do you read? I don’t think you’re someone who reads straight through. I see you as keeping up a conversation, flipping around in a book, seeing how one part reads against another, and so on. I’m inclined to think you make texts meet you when/where you’re ready for them.

JL: I remain a slow reader because, as you surmise, I track part-whole and part-part interactions, and so read cumulatively rather than straight through. From the vantage point of a current word, sentence, paragraph, chapter, even book I am always circling back and marking congruence, tensions, repetition, omissions, etc., treating the whole as a vibrating, expanding web. (A good deal of re-reading thus transpires before I reach the end.) But webs are designed to catch flies, and so I also read for an author’s why. What prompted this inquiry? Is something being negated, defended, both? Wittgenstein is trying to liberate himself from a certain kind of philosophy, perhaps through the labor of another. Beauvoir is offering a version of humanity that could come into its own without a god and without dissolving the ambiguity that underwrites a term like “humanity.” And so on. If I have a sense of what orients the labors of a text I find it much more rewarding to read. And I want the orientation of this text not simply another version of my own. I thus don’t want a pragmatist Heidegger or deconstructive Adorno or the Butler who is more Foucault than less. Emerson says of the friend: I love him because he is not me. I thus want a chorus of texts that resist euphony. That is why there are so many voices in Philosophy, Writing, and the Character of Thought. I come into my own through the interaction of others and the friction thereby generated, which is a way of saying that a question about my reading will lead to my thinking even as a question of my thinking will lead to my reading.

SP: One of the writers I kept thinking about while reading your book was David Shields. His Reality Hunger shares some of your formal concerns, and his I Think You’re Totally Wrong (with Caleb Powell) is one response to your question, “But why don’t we write (or cowrite) actual dialogues?” Are there contemporary non-philosophers whose work has shaped your thinking about writing?

JL: There aren’t, but that’s on me. To the degree I have an excuse it lies with my own effort to keep expanding my philosophical education (and to renew my education in poetry). And of late I’ve been reading so-called Afro-pessimism, particularly Fred Moten and Christina Sharpe, and doing so in the context of the kind of Black Democratic Perfectionism being articulated by Eddie Glaude, Melvin Rogers, Chris Lebron, and Paul Taylor. But no doubt there are smart, smart books I’ve overlooked. For the recent piece on hope I read Rebecca Solnit, who is brilliant, concise, and engaging. And I have also read Lisa Robertson’s Nilling, although it eluded me. But that just led me to order some more of her work so I can try again. At this point, I want more to think about, not less. Since receiving your questions, I also began reading David Shields, and I see the point in your question (and not just because Emerson is all over Reality Hunger). So thank you for the introduction. I’m only halfway through Reality Hunger, reading in the manner we discussed above, tracking recurrent issues such as montage and Shields’s fact/truth distinction, which reminds me of Tim O’Brien’s “How to Tell a True War Story” from The Things They Carried, where he suggests that truths, maybe all truths, are only articulable through selection and omission, and thus contra fact.

Moving from thematics to performance, I found his voice casual, and in a way I often admired. That way of just saying it, a way that Solnit also has, leaves me feeling that my own prose is rhetorically overheated. But maybe those temperatures lead to something that would otherwise go missing; I don’t know. And I’m not above admiration and envy. Strangely, while reading Reality Hunger in the context of this discussion, I keep thinking of Kierkegaard, thereby situating Shields in an aesthetic mode and my text in the ethical. In the parts I’ve read, it seems like a kind of aesthetic truth is orienting him, which includes an honesty about how elusive it is, and a concerted effort to sort through what must be done (and avoided) if one works toward truth in this way. (Lukács’s long, early essay on Kierkegaard, “On Poverty of Spirit” seems apropos, particularly its exploration of the effort to bring life under the dominion of meaning-giving form). I on the other hand, keep returning to what one could regard as pedagogical matters—what will facilitate learning, for a writer as well as for readers, particularly under social conditions that frustrate such efforts, or insist that they conform to definite modes of being in the world. And that is why Philosophy, Writing, and the Character of Thought concludes with discussions of historical bearing, which returns us again to character and exemplification. That sense of representatives (rather than representation) doesn’t seem to concern Reality Hunger. But I’ve another half to go. I’m curious to see where it takes me. I know I’ll take it with me (O’Brien as well) into two papers I have going, one on error, the other on truth.

SP: You are the co-founder with Rick Lee of a journal, Circles. I take it the name comes from Emerson. What are your hopes for it?

JL: Still hopes at this point. I’ve been so busy writing my editing has floundered, though Rick has kept it afloat on-line. The journal aspires to be a home for philosophy written from any tradition and in any form, although Rick and I expect excellence in all cases. I think one should venture different genres and logical rhetorical operations because what called for one’s thinking needed something different than a journal article. But I suspect that we mostly will publish journal articles, although we hope to have an interview in every or every other issue. Regarding the Emerson connotation, it is in full force. Philosophers work in circles, conversing and progressing within those confines. That is not only inevitable but generative, and so we want work that situates itself in and advances some kind of conversation. But each circle is also bounded in ways that genuine thought will eventually rub up against and, if it’s strong enough (to paraphrase), thought will transgress that limit and think anew. The journal’s name thus conveys a commitment to established lines of questioning, the belief that there are a legitimate plurality of such lines, and an invitation to experiment in ways that contest what has, until now, seemed sufficient. I hope we can bring this about.

Click here to purchase Philosophy, Writing, and the Character of Thought

at your local independent bookstore

Click here to purchase Brian Eno’s Ambient 1: Music for Airports

at your local independent bookstore

Jindrich Štyrský

Jindrich Štyrský

Adam Tavel

Adam Tavel

Appearing with Keelan will be Minnesota poet Chris Santiago, the author of Tula, which was selected by A. Van Jordan as the winner of the 2016 Lindquist & Vennum Prize for Poetry, and was a finalist for the 2017 Minnesota Book Award. A 2018 McKnight Writing Fellow, his poems, fiction, and criticism have appeared in FIELD, Copper Nickel, Pleiades, and the Asian American Literary Review.

Appearing with Keelan will be Minnesota poet Chris Santiago, the author of Tula, which was selected by A. Van Jordan as the winner of the 2016 Lindquist & Vennum Prize for Poetry, and was a finalist for the 2017 Minnesota Book Award. A 2018 McKnight Writing Fellow, his poems, fiction, and criticism have appeared in FIELD, Copper Nickel, Pleiades, and the Asian American Literary Review.