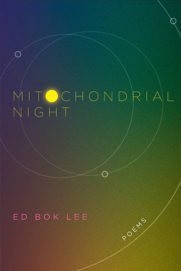

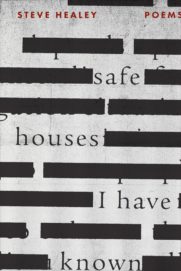

Poets Steve Healey and Ed Bok Lee both live in the Twin Cities and have known each other for over a decade. Both have published a number of poetry books with Coffee House Press, their most recent ones coming out in 2019—Healey’s Safe Houses I Have Known (Coffee House Press, $16.95) and Lee’s Mitochondrial Night (Coffee House Press, $16.95). Both collections were named finalists for the Minnesota Book Award.

There are intriguing overlaps between these books. They both explore fatherhood and family experience in starkly personal ways. They consider how past trauma haunts the present, and how imperial and colonial brutality has continued to manifest new forms through the Cold War and into our twenty-first century.

But these books also come from radically different social positions. Lee writes through the lens of his Korean ancestry, his parents’ experience of physical and cultural displacement as refugees and emigrants, his life growing up in the U.S. with its uniquely insidious ways of marginalizing Asian Americans. In contrast, Healey’s book dissects his white suburban childhood and complicity in his father’s covert professional life as a CIA spy—how that same culture of secrecy infected their family and caused large-scale devastation around the globe.

This conversation was conducted prior to the onset of the Covid-19 pandemic and the killing of George Floyd by a Minneapolis police officer. Of course, the social inequities and atrocities spotlighted in recent months have deep histories and contexts, so it is our hope that readers will find this conversation even more relevant for our current moment.

Steve Healey: Congrats to you, Ed, for publishing Mitochondrial Night—such a powerful book with so many layers. One pervasive theme I find in these poems is how the past, memory, history, ancestry, ethnic identity, all continue to emerge in our present lives and bodies (our mitochondria). Can you talk about how this theme became so important for this book, for you as a poet & person? Is there something empowering and healing about this accessing of the past, tracing these continuities? Is there also something dangerous and destabilizing about it?

Ed Bok Lee: Thanks. And congratulations to you on the incredibly poignant, thought-provoking, formally playful Safe Houses I Have Known. The Cold War as a ghost that has moved so quietly through so many families is chillingly felt in your new book. As the child of immigrants from the two Koreas—my mother from what is now the communist North and my late father having haled from the (capitalist) South—your book makes me think about how the Cold War has affected my own family. Maybe we’ll get more into that. But, to your question, I’ve spoken before about how our cellular mitochondria, with their own “invasive” history and specific DNA, seemed like an apt, centralizing metaphor for Mitochondrial Night. My book explores what it means to be a migrant, a refugee, an immigrant, by looking at certain commonalities not only between all humans, throughout history, but also fundamental commonalities between all seeds, stars, cells, and ancestors.

One thing I haven’t touched on before is the Korean cultural patriarchy. This is changing slowly due to #metoo and other social injustices coming to full light in the digital age, but bloodlines on one’s father’s line are still to this day immensely important, especially to the classes that have the most to maintain in terms of power. Becoming a father for the first time, as well as becoming very aware that my mother doesn’t have much time left on this Earth, catalyzed something very deep in me. I wasn’t taught by any culture to think this way, but often when looking at my daughter, it’s very clear to me that I’m literally half my mother, half her genes and in many ways, also half her physicality. I see myself more wholly through my daughter. I see my mother more wholly as a human being through my daughter. I think I can also see certain glimpses of all of humanity through my daughter. A lot of men grow up identifying more physically with their fathers—that is, we often look for our wholeness as a man through our fathers—yet we’re half our mothers, and partly their mothers, their mother’s mother, and so on, ad infinitum, back to what biologists term “Mitochondrial Eve.” (Mitochondria, the energy factories in each of our living cells, is inherited solely matrilineally.) The book is dedicated to my mother, a refugee three times over before she was ten years old, and also was written with my daughter’s future questions about who she is and where she comes from in mind—questions that I realized I can't truly ever hope to answer until I satisfactorily pose those questions to myself, and not just as a current member of the human species.

One thing I haven’t touched on before is the Korean cultural patriarchy. This is changing slowly due to #metoo and other social injustices coming to full light in the digital age, but bloodlines on one’s father’s line are still to this day immensely important, especially to the classes that have the most to maintain in terms of power. Becoming a father for the first time, as well as becoming very aware that my mother doesn’t have much time left on this Earth, catalyzed something very deep in me. I wasn’t taught by any culture to think this way, but often when looking at my daughter, it’s very clear to me that I’m literally half my mother, half her genes and in many ways, also half her physicality. I see myself more wholly through my daughter. I see my mother more wholly as a human being through my daughter. I think I can also see certain glimpses of all of humanity through my daughter. A lot of men grow up identifying more physically with their fathers—that is, we often look for our wholeness as a man through our fathers—yet we’re half our mothers, and partly their mothers, their mother’s mother, and so on, ad infinitum, back to what biologists term “Mitochondrial Eve.” (Mitochondria, the energy factories in each of our living cells, is inherited solely matrilineally.) The book is dedicated to my mother, a refugee three times over before she was ten years old, and also was written with my daughter’s future questions about who she is and where she comes from in mind—questions that I realized I can't truly ever hope to answer until I satisfactorily pose those questions to myself, and not just as a current member of the human species.

Your own book contains many poems about growing up as the son of a CIA agent during the Cold War. Yet I’m as intrigued by the mother’s silence as I am the father’s silence (or secrets). I find myself wondering what it was like to be her? What was shared with her, what was not? In this way, the State enters into her unspokenness like a third patriarchal (to the child) figure. Can you speak to what was healing and what was destabilizing in the process of composing this book in poems?

SH: Great question—you’re getting at something that was really unexpected for me while writing this book. I’d thought it was mostly about my relationship with my father—how he lived a secret life as a CIA spy, how he descended into mental instability and alcoholism, and then died decades ago at the age of 62.

But my mom is still alive, now 80 years old, and I still feel the effects of this past family history in our present. We’re very close, but she’s always been a private person who doesn’t talk much about feelings, and I was getting anxious and uncomfortable about that long “unspokenness.” So the last poem I wrote for the book, “How I Become a Son,” was one I never thought I’d write while my mom was still alive. It reveals some particularly painful events that triggered my parents’ divorce. I decided to share the poem with my mom, and we finally talked about what had happened, and it was such a relief to break that silence.

But my mom is still alive, now 80 years old, and I still feel the effects of this past family history in our present. We’re very close, but she’s always been a private person who doesn’t talk much about feelings, and I was getting anxious and uncomfortable about that long “unspokenness.” So the last poem I wrote for the book, “How I Become a Son,” was one I never thought I’d write while my mom was still alive. It reveals some particularly painful events that triggered my parents’ divorce. I decided to share the poem with my mom, and we finally talked about what had happened, and it was such a relief to break that silence.

You’re totally right about that silence being bigger than individuals—it was (still is) built into the State and the larger culture. In a way, it was the coldness of the Cold War, and my mother was produced by it like so many others. She came from an Italian Catholic family, and her own father was a demanding, abusive man who actually tried to erase his ethnic identity, changing the family’s last name (Loschiavo) to one he thought would assimilate more into mainstream American whiteness (Higgins). My mother was ordered not to reveal their true Italian identity to anyone, so she too lived “under cover” while growing up.

I think deciding to divorce my dad was her most powerful act of self-expression, her way of gaining some control in her life. But as so many poems in Safe Houses I Have Known show, we still didn’t have the tools to cope with the psychic mess that unfolded from there. We still didn’t know how to talk about it.

I’m wondering about how you depict your mother in Mitochondrial Night, especially in a poem like “Metaphormosis,” not only as someone who remembers or connects you to various pasts, but also as someone who increasingly forgets. Later, there’s a poem called “Portrait of a Blind Couple Reverberating,” with these great lines: “Each body is an ark. We store enough / clarity and obfuscation to survive.” How might obfuscation and forgetfulness be ways of surviving? Your book obviously yearns for memory and clarity, but do you see obfuscation and forgetfulness operating in these poems as well?

EBL: This idea of forgetting is interesting, especially given that some old people, as they’re losing their memories, seem to remember things they haven’t experienced in years, like a childhood song or figure from their childhood. I don’t mean to romanticize losing one’s memory. But I’ve been thinking lately that every human being is drawn to poetry at an instinctual level, in part because when you’re an infant and teetering toddler, everything in the world, every sound and image and sensory detail, is new and mysterious and just beyond comprehension, yet monumentally present, even potent. In short, the world and everything suffusing us in it feels like a powerful, slowly unfolding poem. I don’t think we ever really lose this relationship to the poetic. At some point, we convince ourselves that we can finally now understand the world in a rational way as adults. But it’s all akin to an illusion. Ask anyone on their deathbed. The world, life, was one long poem, they will tell you just before they close their eyes for the final time.

Knowledge, it seems to me, is parochial, as is “reality.” Ask any scientist from a hundred or a thousand years ago about the nature of “reality.” As Richard Wright wrote, in part in the context of Black and White America, “Literature is a struggle over the nature of reality.” On that tip, power just as much as poverty warps one’s experience of “reality.” Thus, some who are powerful are often simply doing what they feel with every bone in their bodies is moral and just and for the betterment of all. So it’s not necessarily that they’re evil, or gone over to the “dark side,” as some would have it, or are even lying to themselves to remain sane. It’s that their reality, the formation of molecules around them and everyone else around them (also usually powerful) is a kind of different plane of existence. But the error comes too often in the sense that that plane is inherently superior. I think poetry can be very useful here.

In the case of Safe Houses I Have Known, the father is co-existing in two different realities, with two different identities. Once the son, you, learns of his secret in adolescence, and especially after the divorce, it’s as if the speaker gets atomized, disintegrated, spread so thinly across various competing realities. This is where poetry comes in, as a form to hold all these disparate realities into one larger, more comprehensive and cohesive whole. If you’d written a prose memoir, I wonder how you would have been able to get at the kind of disembodied psychic state of the speaker and situation and nation. The U.S. and world was living for the first time in a constant mode of potential sudden annihilation.

In “Invisible Civil War,” you write of a neighbor boy, Brad, who later killed himself as an adult. The speaker articulates: “I wish I were making this up, but I’m not. It’s really true that / I threatened to kill him if he didn’t sponsor me for a charity walk. / I must have needed an easy way to forget my own pain by / threating someone who was nervous and spoke with a stutter.”

We then learn that these boys live in “Stonewall Manor,” which was named after “’Stonewall’ Jackson, / the Confederate general known for killing many Union solders,” and that the speaker’s parents are in the process of divorcing. The recursive nature of the poem, with its repeating lines and sentiments, captures the speaker’s deep urge to both remember and forget what the people in the poem are striving so hard to remember and forget. The final result is silence and death. Yet the poetry lives on.

Do you see any useful parallels or differences between the constant threat of the Cold War in your childhood, and the constant threat of terrorism in our children’s and all our lives in America now?

SH: For sure, the supposed threat of terrorism we still live with is really an extension of the Cold War threat, and then you can keep reaching back in history (to the Civil War, etc) to see this pattern of gaining power by creating a false threat of the “other.” In the Trump era that bogeyman has become the immigrant or refugee, and clearly Trump became president by magnifying that threat to provoke fear and resentment.

As you say, those in power often really believe that they’re doing the right and moral thing, creating “security,” protecting people, even while devastating others along the way. As I was doing research for my book, I confronted so many disturbing atrocities the CIA committed “to save the world for democracy” from the “Communist threat,” and those who suffered most were often poor, nonwhite people, often in former colonies, in Asia, Africa, Latin America. It occurred to me that the modern intelligence industry was built to continue colonial control in less obvious ways. As overt colonial rule became too messy and morally questionable, global superpowers invented covert operations to make their power less visible or more justifiable.

That bullying I describe in “Invisible Civil War” is a true story, and I still feel great shame for threatening that kid in that way—I’m still haunted by that memory. And yes, that tension between remembering and forgetting in the poem—it happens not just on a personal level for the speaker and me, but also on larger social and historical levels.

In a way, that suburban neighborhood was like a monument to forgetting the real Civil War, a whitewashing of the real racism, pain, and death. The suburban American dream says, “Let’s forget the trauma, keep smiling, keep moving forward.” But of course the trauma keeps manifesting and repeating, not only in little acts of bullying but also in the anxiety and paranoia that pervade society, in systemic inequities, and in State-sponsored acts of mass violence and war.

I love that idea of life being one long poem, experienced most intensely by those recently born or about to die. Do you think becoming a father for you has been a kind of link between these two spaces? The speaker in Mitochondrial Night so often composes the world of the poem around his daughter, observing her, but also observing himself as a parent. How has becoming a father inhabited your poetry or changed it? Do you write differently now?

EBL: She was born in 2016 (the first year of this current presidential administration), and I think this intensified the experience of both events. But it’s hard to generalize. As much as a parent, I feel like a steward of this “new” soul on earth. Watching her go through phases of what Piaget termed disequilibrium and equilibrium, and learning these cycles continue throughout one’s entire life, albeit at varying lengths, lately makes it clear to me that we’re presently in a social and cultural stage of disequilibrium. Just look around and listen not only to what people are saying, but to the quality of their voices. I think writing is like that, too; even the creation of a poem, even a single line.

As the son of a man who was spy for the CIA, did putting the poems and book together in any way give you any revelatory perspectives on him that you wouldn’t have otherwise arrived at? Which of these perspectives, if any, have been most surprising? And what do you think he would have thought about the book?

SH: I think my father would’ve been okay with the book’s larger critique of the CIA and U.S. interventions abroad. Earlier in his career he believed he was doing ethical and patriotic work, helping to prevent World War III, but late in his life he grew pretty cynical and disheartened about his CIA career. I don’t think he fully reckoned with the devastation the CIA caused—propping up brutal right-wing dictators, training death squads, etc. But he occasionally talked about how the CIA consumed enormous resources but never really accomplished much, and how some of its biggest intelligence victories were just happy accidents, like some janitor walking into an American Embassy asking if they wanted to buy a classified document he’d found in a trash can.

Safe Houses also looks at the personal tragedy of my father’s life, and I’d probably be less comfortable sharing those poems with him—the fact that he’s been dead for over two decades perhaps gave me the distance to be more blunt and honest. I think what surprised me most is when I started to admit that my father had severe but undiagnosed mental health problems. He was actually very kind and gentle as a father, but he was deeply troubled, probably battling depression, anxiety, and suicidal thinking for many years. The title poem, “Safe Houses I Have Known,” and another one called “Drinking,” show my dad at his rock-bottom worst.

That Piaget term “disequilibrium” could certainly describe the last half of my father’s life. He was never able to find equilibrium. And I agree that disequilibrium happens on larger levels of society and culture. I see my book as at least partly investigating the dysfunction of privilege—this might connect to what you said earlier about how power warps reality as much as poverty does. I grew up with all the safety and benefit of my white suburban middle-class life, but there was something broken or diseased at the core of that privilege. I have my story of that dysfunction, but so many other people who grow up with privilege have their own stories. And I really believe these stories need to be heard—we need to keep diagnosing the dysfunction, because that can help move us closer to equilibrium, equity, empathy, justice.

I wonder how that social disequilibrium might be reflected in the formal aspects of Mitochondrial Night. I’d say your poems—more than those of many other contemporary poets—have a wide range of impulses, so they don’t all look the same on the page. There are compressed associative lyrics, like the amazing “Reading in Bed Is Like Heaven.” There are prose poems—or almost prose poems—driven more by narrative or essay-like inquiry. And there are others that mash-up multiple formal impulses. Why are you drawn to this kind of formal range, and is there any connection to what’s happening in the world?

EBL: Here’s a terrible (but hopefully terribly effective) metaphor. Anyone into martial arts knows that the most effective style of defense/fighting is no one single style of martial arts; the most effective method is to become familiar with many styles to be employed as the ever-shifting situation requires. In an actual fight, in the ring or bar or street or combat field, the more styles of martial arts you’ve become familiar with, the better you can hope to deal with the wild, unpredictable force of the matter that is rushing toward you. I think poetry is similar. If I’m going to take on a poem, I’m less interested in poems that don’t risk hurting me with their sometimes hidden weapons of awareness and insight. In other words, in extreme cases, regarding form and content, is it better to have a naked human being running around wild, screaming gorgeous, haunting, ear-splitting songs, or a fashionable, impeccably dressed corpse? Both are a kind of death.

In Safe Houses, you employ many forms such as pantoums and erasure poems to contain the often raw and gangly emotions and subject matter. It seems to me that living as a spy is all about formalities, and yet what about the incredibly messy human being within the vessel of the professional formality? We all experience this to varying extents, because we all subscribe to identities. Can you pan way out and speak to what surprised you most about what the various forms you employed yielded—things you perhaps hadn’t even seen in the material before examining them through the prisms of these forms?

SH: I get what you’re saying about cultivating a multitude of styles or forms, whether in martial arts or poetry. I’ve seen this impulse especially when I teach creative writing—I find myself trying to help each student become many different kinds of writer. I don’t want them to find their “one true voice,” which the traditional workshop model encourages, but to keep gathering diverse approaches and techniques, always defamiliarizing themselves.

In this new book I explore traditional form a lot more than I have before: pantoum, villanelle, haiku, sestina, ghazal, rhyming couplets. Some of the poems follow traditional rules more closely, but some are more flexible, occasionally adjusting the rules beyond recognition. The pantoum-like poems scattered throughout the book—they use tercets instead of quatrains, and each stanza only repeats one line instead of two from the previous stanza. But they still have that spiraling pantoum motion, and I found this variation to allow more nuance for the material.

For a long time, I was kind of terrified of traditional form, afraid I’d either fail at it or it would limit me too much. But I’ve been learning how liberating it can be. The constraints led me to all these unexpected, weird, off-kilter ways of organizing my life on the page. I found that you can be loose and playful with it while still respecting where it comes from. Which makes me wonder—can poetic form have that kind of mitochondrial memory you investigate in your book? I mean, whenever we build a poem, either in traditional or organic form, are we tapping into a poetics DNA?

I like how you see the forms in Safe Houses containing the “messy human being.” I agree—that plunge into autobiography needed something else to hold it together, like a spy needs identities or safe houses, like we all need just to survive in the social marketplace.

But there’s the danger of losing the balance, suffocating in that identity. Maybe that’s what happened to my father—he covered up his messy self so completely, eventually he couldn’t breathe.

Click here to purchase Mitochondrial Night

at your local independent bookstore

Click here to purchase Safe Houses I Have Known

at your local independent bookstore

William Gibson

William Gibson