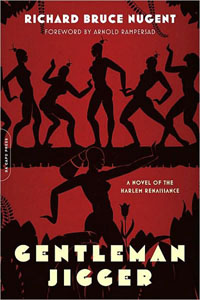

Richard Bruce Nugent

Richard Bruce Nugent

Da Capo Press ($18)

by Douglas Messerli

If you prefer the pious potboilers of Toni Morrison and Alice Walker to the irreverent interrogations of Amiri Baraka and Ishmael Reed, better skip Richard Bruce Nugent’s Gentlemen Jigger, a fiction—written in the 1930s, but published here for the first time—which even in its title hints at its “incorrect” attitudes (the title, Thomas Wirth notes in his Introduction, “is a sardonic riff on an old racist ditty: ‘Looky, looky, Gentleman Jigger—half white and half nigger.’”) And Nugent, through his witty alter ego Stuartt Brennan, uses the “N” word enough, as did Whoopi Goldberg recently on the television show “The View,” to draw tears of frustration not only from Elizabeth Hasselbeck (a fellow panelist on that show who, after hearing Goldberg’s outburst, began to cry) but from any well-meaning correctionist.1

Nugent, the bad boy provocateur of the Harlem Renaissance, dared to speak out in the late 1920s not only about racist attitudes against darker-skinned blacks within the African American community, but also about that community’s prejudices against homosexuality. Along with younger black figures Wallace Thurman, Langston Hughes, Countée Cullen, Aaron Douglas, and Zora Neale Hurston (Nugent, Thurman, Hughes, and Cullen all being gay or bisexual), Nugent challenged readers through the publication of the journal FIRE!! to consider their brothers and sisters less as part of an essentialist community and more as often eccentric and contradictory individuals. Meant to shock, Nugent’s contribution was a drug-induced dream story, “Smoke, Lillies and Jade!” about an encounter with the narrator and a male Hispanic pickup who he calls Beauty.

A son of a noted Washington, D.C. family (his mother was a Bruce), Nugent was so light-skinned that when he first arrived in New York he lived for a few days in a whites-only hotel, and apparently, when he was first introduced to the dark complexioned Thurman, he excused himself, confused over his own racist feelings, an event presented in this passage in Gentlemen Jigger:

It was just as Stuartt was succumbing to the invitation of the food that Tony pointed to the table and said, “There is Raymond Pelman.”

It was a distinctly unpleasant shock—so unpleasant that Stuartt lost all desire for food. Silent and empty-handed, he followed Tony to Pelman’s table. So this was the brilliant Raymond Pelman—the Negro from whom he had expected so much. This little black man with the charming smile and sneering nose, with sparkling, shifting eyes and an unpleasant laugh.

Stuartt decided that Pelman was not to be trusted. He was too black. Stuartt had been taught by precept not to trust black people—that they were evil. And Stuartt was the totality of his chauvinistic upbringing.

. . . Stuartt felt decidedly uncomfortable in his presence. So, after a polite ten minutes of torture, he took his leave.

Returning to Thurman later, Nugent apologized for his behavior, and soon after the two became close friends, sharing a room in what they proclaimed Niggeratti Manor, a rooming house owned by businesswoman Iolanthe Sydney, who charged many of the Harlem writers and artists little or no rent.

From the beginning Nugent, like his character Stuartt in this roman à clef fiction, was an absolute charmer—he had previously worked for Buster Keaton and Rudolf Valentino—and was blessed with an intelligence and wit that, when combined with Thurman’s own brilliant patter, thoroughly entertained and educated their frequent visitors. Indeed, the first half of Gentlemen Jigger consists of many of their witty conversations and descriptions of their frequent and sometimes outrageous parties, replete with pretty boys, beautiful women, and plenty of gin. The characters Nugent presents—most of them fairly recognizable to anyone acquainted with the artists, dancers, and writers of the day, the central ones of whom are Rusty (Wallace Thurman) and his boyfriend, a white Canadian nicknamed Bum; the beautiful Myra (presumably Zora Neale Hurston); her lover the Jesus-look-alike Aeon (represented as Stuartt’s brother, but in actuality probably a mix of Claude McKay and Jean Toomer); the noted white writer, photographer, and sponsor of Black writers and artists Serge Von Vertner (Carl Van Vechten); and Tony (Langston Hughes)—attend to the conversations of the duo, intelligently responding and debating with them. Some of these discussions are just witty riffs on sexuality and drinking. On their way to a picnic, Myra and Aeon are unexpectedly met by Stuartt and Rusty:

“We are cupids—thoughtfully, one of each color, one in each of your honors. Every young and beautiful love should have its quota of obstacles and chaperones. Consider us the more evil of these.”

“Did you bring the gin?” Rusty asked. “I see Myra brought our lunch.”

“I brought ‘green dawns’ after seeing what you were bringing to read aloud.” Stuartt turned toward Aeon and Myra. “Firbank and Proust,” he explained. “Dawns are wonderful,” he continued without pause. “One part absinthe, one part alcohol, tinted with crème de menthe and sparkled with lime and fizzy water—cool as lemonade and potent as—”

“Let’s leave sex out of it,” breathed Rusty, “particularly such gutter and dialect as is mouthed by juveniles.”

“Oh, what you said!” Stuartt chattered as he poured several cups of the incredible pastel drink from a mammoth Thermos. After handing one to each of them, he took another and started to the forward part of the bus, saying over his shoulder, “Oats for the uniformed horse—he looks unhappy.” A few moments later he could be seen offering it to the bus driver.

But in the majority of these intellectualized Bouvard and Pecuchet-like interchanges, they are painfully self-aware in their conversations of the political and racial issues surrounding their lives. In their first conversation with Bum, for example, when Thurman’s Canadian friend admits that he has no knowledge at all about the Harlem Renaissance, he is “lectured” by the two:

“First of all, Bum, I suppose you have never known a Negro before. That’s the usual defense. And you expected to find us more or less uncivilized denizens of some great jungle city, believing in witch doctors and black magic and all that. Well, you’re right. Or maybe you’ve read Harriet Beecher Stowe and feel sorry for us. Do. Or Octavius Roy Cohen and are amused, or Seabrook and are afraid. You know, Rusty, it really is too bad we aren’t more different. What a disappointment we must be.”

Rusty synchronized into the routine. “Well what can you expect. A group of people surrounded for a hundred years or so by a culture foreign to them. How long can you expect it to remain foreign?”

Later in the book, among several long comic dialogues, Stuartt takes issue with the group’s praise of fellow artist Howard (likely Aaron Douglas), dismissing their comments that Howard’s work is “essentially African” by noting the absurdity of describing anything as “African” and brilliantly expounding on the vital differences between a “Gabun full figure,” and art from Sudan, Congo, or by a Benin native. Like a true didact Stuartt explores the complexity of this issue, remarking to Rusty, “Remember these things. . . if ever The Bookman wants an article on Negro art.” In this sense, Nugent’s fiction is less a recounting of the lives of him and his friends, and more a complex discussion of various issues involving art, race, and sex.

Accordingly, for some readers Nugent’s dialogic writing will seem like a bumpy, baggy affair, with what critic Northrup Frye has described in his Anatomy of Fiction as “violent dislocations in the customary logic of narrative.” Indeed, the editor of the Portable Harlem Renaissance Reader characterized Wallace Thurman’s fiction, Infants of the Spring—a work written at the same time as Nugent’s which often incorporates scenes similar to Gentleman Jigger (in a biopic about Nugent, Brother to Brother, friends even accuse Thurman of copying from Nugent’s manuscript)—in terms that might equally apply to Nugent’s writing: “The novel was melodramatic and much too didactic, its talkative characters caricatures.”

As Frye warns, however, in works such as Nugent’s (and Thurman’s) “the appearance of carelessness reflects only the carelessness of the reader or his tendency to judge by a novel-centered conception of fiction.” For both of these fictions are anatomies, not novels, a satiric form of fiction that “deals less with people as such than with mental attitudes.” The major figures in such works are represented as “pedants, bigots, cranks, parvenus, virtuosi, enthusiasts”—all of which might describe Stuartt and Rusty (or Paul and Raymond in Thurman’s work)—who suffer the disease of the intellect. Here the country weekends of Thomas Love Peacock, Aldous Huxley, and Wyndham Lewis, where the pedant captures the attention of his guests over drinks and long dinners, is replaced by the raucous celebrations at Niggerati manor and dinner at Devores.

Another structural aspect of anatomies is the tendency, as in Petronius’s Satyricon, to gather together individuals representing all social classes and/or to represent the pedant-hero undergoing a voyage that includes both the upper echelons of society and the underworld. It should come as no surprise, accordingly, that after Stuartt’s encounter with the Harlem underworld—ending, as it does in Thurman’s book, with dispersal and disillusionment—the second half of Gentleman Jigger takes us through another kind of underworld, the Mafia, in which low-class figures live aside the wealthiest classes of U.S. society.

The Stuartt we encounter in part two, now living in Greenwich Village, is almost a new being; he has grown his hair long, and, as Bum describes him, “the kid sparkles.” Whereas in the first half of the fiction Stuartt presented himself as a knowing wit, here we see him admitting to Ray, a young handsome Italian vaguely connected with the mob, that he has never had a gay sexual experience before. His clumsy attempts at love are met with a feeling from Ray that he needs to protect and educate the innocent neophyte. This new Stuartt, moreover, although still very much a philosophus gloriosus, is far more modest and honest in expressing his ideas. In Niggerati manor he lived without a job in utter poverty; now he is selling his art, and his apartment has become a meeting place for Village artists, young hoodlums, and visiting art patrons—the perfect location, of course, for his further musings on various subjects, sacred and profane.

So fabulous are the characters in this section that it becomes hard to tell whether or not Nugent is still writing a roman à clef or has abandoned it for pure fantasy. If the events are accurate, as Wirth suggests, we must rewrite the annals of gay history to include noted Mafia members. But in another sense, it makes no difference, since the overriding structure of the book continues to be the form of the anatomy.

After his affair with Ray, Stuartt moves up the Mafia social ladder by taking up with “the biggest shot known to Ray,” Frank Andrenopolis, the so-called “Artichoke King,” (a character likely based on mobster Ciro Terranova, who controlled much of New York before “Lucky” Luciano). Although generally heterosexual, Frank, who has been turned into the police by his moll, casually begins a sexual relationship with Stuartt that only enhances the young artist’s reputation. On a trip to Chicago, the two encounter the big mob leader, Orini (based on Luciano), to whom Stuartt takes an immediate disliking; offended, Orini drives Stuartt to his lakeside mansion, undetermined whether to beat him or make love. Playing dangerously with Orini’s notions of manhood, Stuartt escapes the beating, and woos the mobster into bed. Stuartt also attracts the attention of Bebe, Orini’s mistress, and threatens to sign her and himself as dance performers at a local club, unless Orini is willing to buy her out of the contract.

Next door to Orini’s mansion Stuartt encounters the socialite Wayne Traveller (probably based on Grace Marr, with whom Nugent formed a platonic relationship and later married); she further promotes Stuartt’s career. More success follows, as Stuartt, presumed to be white, does the costumes for a musical (in real life, Nugent had a non-speaking role in Dorothy and DuBose Heyward’s Porgy) and dances in a film with Bebe. In the midst of these joyous activities, however, a young boy enters the theater asking for donations for the Scottsboro Boys, and Stuartt, requesting his weekly payment, hands over the check for $3,000. Later, queried by a gossip columnist who finds his gesture a strange one, Stuartt answers: “I can’t see why it’s so funny, though. No one seems to think it strange if a Jew helps a Jew. But it’s news if a Negro helps a Negro, I suppose—.”

With that, Stuartt’s career comes shattering down upon him, as racism wins the day. Unlike Thurman’s novel, however, in which the Nugent character Paul Arabian commits suicide, Nugent turns the tables, so to speak, in his own fiction. To buy him out of his contracts, he is paid $100,000—the amount he has previously told Orini he would need to survive for the rest of his life!

So too did Nugent prevail, outliving most of the figures of the Harlem Renaissance. And while the character Nugent in the biopic Brother to Brother is presented as being homeless, in reality the artist lived out his life modestly in Hoboken, continuing to meet with the board of the Harlem Cultural Council, an organization he helped found years before. Yet there is still something terribly sad about this satiric masterpiece and Nugent’s own life, for in the end his is a story about intelligent, loving, and beautifully youthful individuals trying to survive in a world of general stupidity and hate.

1The discussion on “The View” about the “N” word is far more relevant to the issues above than one might imagine. This discussion, brought about by Jesse Jackson’s use of the word over what he thought was a closed mike, led Goldberg to argue that white people’s use of that word meant something far different that its use in the black community, where its hateful meanings had been transformed into something that was used in different contexts—perhaps akin to the gay community’s reclamation of the word “queer.” At the time of Nugent’s novel, the white author (and long time friend to many Harlem Renaissance writers) Carl Van Vechten had just published his view of Harlem in Nigger Heaven; upon publication of the novel many of Van Vechten’s friends, black and white, were outraged and hurt. Nugent’s use of the word in Gentlemen Jigger also makes his friends quite uncomfortable, although they recognize that he is being a provocateur.

Click here to buy this book from Amazon.com

Click here to buy this book from Powells.com

Rain Taxi Online Edition, Summer 2008 | © Rain Taxi, Inc. 2008