Grant Morrison, Richard Case, et al

Vertigo ($19.99 each)

by Ken Chen

What is a “novel of ideas”? The phrase is most frequently slapped on alpha male novels, swaggering to diagnose contemporary politics and mores, stacked up with bricks of data, historical trivia, and straggling cast members, and striding eagerly towards a shaggy ambition: to encompass everything. Yet what could be further from the world of ideas than a gluttonous story, eager to swallow the world? And, to tip-toe this argument a step further, what could be more antithetical to an idea than an actual story, less fresh and novel than the novel, that aggregator of empirical life and proper nouns, with every prop nailed firmly into this time and that place? Speaking as one who has long preferred books that levitate, buoyed up by ideas, what I would like is a genre of books about nothing, one that possesses zero time and zero place.

Many books fall within this hopped-up, helium category, but the work of comic book writer Grant Morrison nicely illuminates what it means to look at fiction not as a medium of stories, but of ideas. Morrison is perhaps the most creative writer of comics in English, and his idea-crammed virtues and vices can be seen in Doom Patrol, a superhero comic he wrote from 1989 through 1992, but whose characters existed for nearly thirty years prior. Writers Bob Haney and Arnold Drake created the original Doom Patrol, with artist Bruno Premiani and editor Murray Boltinoff, as a misfit inversion of the typical superhero group; the characters gained their powers through traumatic accidents (e.g. a totaled car, a plane crash) and had less kinship with photogenic supermen than with counter-cultural outsiders—much like the X-Men, another rebel superhero team that, apocrypha suggests, was a Doom Patrol plagiarism.

Morrison transformed Doom Patrol by interpreting its central trope— the superhero as freak—as an engine for freewheeling stories about psychedelic bicycles and magic dentures. One of his characters, Kay Challis, serves as a synecdoche for the whole project: abused as a child by her father, Kay’s trauma manifested itself as a strain of multiple personality disorder in which each of her sixty-four personality possessed a different superpower. While Morrison does use Kay to explore how an adult deals with child abuse, he seems more interested in writing a character that can always shed its skin and in writing a comic that is never finished, eternally new, and always spitting out possibilities.

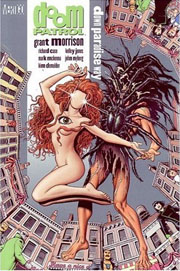

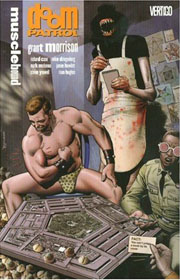

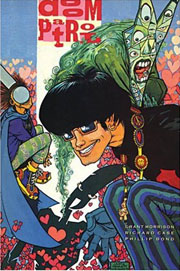

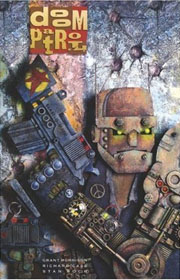

DC’s Vertigo imprint recently collected Doom Patrol in six volumes whose titles—such as The Painting That Ate Paris, Down Paradise Way, and Planet Love—serve as surprisingly apt keywords for Morrison’s aestheticism: he’s an absurdist, counter-cultural science fiction writer appropriating the civilized arbitrariness of the Dadaist flaneur, the joyful pastiche of ‘80s camp, and the mystical utopianism of hippie lovefests, English Romanticism and the Western tradition of magic. This is baroque brain-pop in which the protagonists—conceptual “superheroes” like Robotman, Danny the sentient (and transvestite) street, and Flex Mentallo, Man of Muscle Mystery—fight a man who hunts beards, a woman possessing every superpower you haven’t thought of, and the Men from N.O.W.H.E.R.E.

As you may have guessed by now, Morrison is a prolific inventor and, unlike most fiction writers, he does not see his job as the layering of details. In fact, reading Doom Patrol reminds one how much conventional novels are really about logistics. And while Doom Patrolwould have been disastrous as a novel, the comic form gives a visual specificity to a story that essentially avoids a setting and a focus on things. Most of Doom Patrol is drawn by Richard Case, whose dilapidated style possesses enough earth to ground Morrison’s vamping and enough wonkiness to animate Morrison’s cheerful lack of empiricism.

Morrison deploys two seemingly opposite traditions to help him generate, rather than develop, ideas: mystic allegory and action movies. While Morrison is obviously influenced by Western magical traditions—in one issue, Doom Patrol fights the sky-deleting eye of the Gnostic Decreator—this obscure canon may have had the more subtle effect of liberating his idea of character. Just as the Talmudic angels wore four faces so they would always gaze towards God, and just as the characters from Tarot cards are not persons but symbolic diagrams, the supporting characters in Doom Patrol are not psychologies possessing a past and future, but rather images nailed together into a compound meaning—such as the Candlemaker, a winged demon whose forehead fuses a vertical eye and a candelabra, or schizophrenic secret agent John Dandy, a naked man wrapped in twine, eyes covered by Scrabble letters and mouth by comb, head haloed by seven bald heads. Like Dadaist poetry, we cannot easily adjudicate whether such creations possess literary “quality,” but Morrison is an artist less interested in whether an idea is good, as long as it is interesting.

Once these characters are cobbled together, Morrison drives them like bumper cars through an action movie plot. The thrill of an action movie is not entirely different than the thrill of a lyric poem; both present ways of organizing intense effects. While Doom Patrol has obvious action-movie motifs—unashamed cliffhangers, images of devastated cities, and faux-tough guy patter—on a deeper level, it possesses the intellectualism of an action movie. Action movies are abstract surfaces, machines of plot that do not rely on our understanding of the world (as a realist movie might), but on an artificial framework the movie itself has created. This is why the action movie is so amenable to fantasy and science fiction (and Morrison’s strangeness)—it is already a closed context. Morrison deploys these action movie logics not just because of the kiss, kiss, bang, bang and the plot twists, but because they render his weirdness familiar. Several Doom Patrol stories culminate in a showdown with an unspeakable horror that we previously glimpse only via the supporting cast’s stunned reaction shots. While such climaxes may seem clichéd, they suggest that Morrison is really interested in the concept of the Sublime, the beauty that terrifies us. It is a problem he explores more deeply in later projects, such as The Invisibles and JLA, both about staving off an inevitable apocalypse, and his New X-Men, which actually features a villain called Sublime.

Morrison may explore a theme like the sublime, but you never sense that he’s searching to understand a given topic; his themes, rather, are conceits through which he can course his thoughts like electricity.Doom Patrol, for example, is an anti-dualistic comic: Morrison seems bored by the value-trapped bipolar world of heroes and villains, particularly when the Doom Patrol faces the Brotherhood of Dada, whose absurdist antagonists seek nothing more than to liberate the world from tedium. And the members of Doom Patrol even expostulate on their anti-dualistic postures, like Rebus, who is both man and woman, black and white, and Robotman, who argues with his metal body. One suspects Morrison sees his throw-in-the-kitchen-sink pastiche as a way of enlarging his work, which pinballs from high to low culture, and from future to past. But because Morrison’s goal is to explore a diversity of styles rather than things, and because he does not develop a single style, a style so natural that it no longer seems a style, Morrison is an ironic aesthete, not a fecund storyteller like Tolstoy or Dickens (or, more appropriately, Kirby/Lee on Fantastic Four or Claremont/Byrne on Uncanny X-Men). For some readers, then, Doom Patrol will seem too inorganic, arcane, and apathetic about character. (Morrison, incidentally, writes characters not as selves, but as quotations from different literary styles.) Yet I think Doom Patrol is a personal comic, but personal the way a poem, rather than a novel, is personal—in its aesthetic. As with the New York School poets, you are always aware of how much fun Morrison is having jolting the page with ideas. His mind lights up in vigorous sparks, illuminating Doom Patrol with an idiosyncratic human smallness, much like the novels of Flann O’Brien (whose At Swim Two Birds is, like Doom Patrol, fascinated with the color green), the fictions of Donald Barthelme, or even—work with me here—the short stories of V.S. Pritchett.

Doom Patrol came out within years of several comics that validated the medium for an adult reading audience: Alan Moore’s Watchmen, Frank Miller’s The Dark Knight Returns, Neil Gaiman’s Sandman, and Art Spiegelman’s Maus. But Morrison’s jumpy eclecticism reads like a preemptive rebuttal to these dour modernist masterpieces. While these comics sought to be respectable, realist, somber literary works, Morrison’s Doom Patrol is gleeful whimsy, full of aesthetic “mistakes,” and narratologically less similar to the psychological novel than it is to Burroughs and Borges, The Prisoner and Dennis Potter. Don't be scared off by Morrison's obscurantism or his obvious love of superhero comics (which are almost always appropriated with loving irony)—just revel in a comic that will tell you nothing about what it is like to be alive, but is instead giddy on what Apollinaire called "a liberty of unimaginable opulence."

Rain Taxi Online Edition, Summer 2008 | © Rain Taxi, Inc. 2008