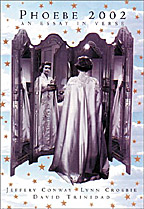

The Midnight

The Midnight

Susan Howe

New Directions ($19.95)

by Michelle Mitchell-Foust

I recently visited an exhibit called "Two Rooms," featuring installations by the artist Rosamond Purcell. The "rooms" were first, a "Recreation of scientist Olaus Worm's room," a cabinet of curiosities which Worm created in Amsterdam in 1655, and second, a reconstruction of Purcell's studio in the Eastern United States. Purcell is famous for photographing naturalia from museum collections; her collaborative books with the late evolutionary biologist Stephen Jay Gould feature photographs of bones, shells, husks, feathers, and organs suspended in chemical fixatives. Purcell is a photographer, researcher, collector, arranger, and writer whose pieces carry titles such as: Grown Round By, Chair for Olaus Worm, Picture Stones and Figured Roots, Metal Wall, Overflow, Cement Slabs Used to Weigh Down Lobster Traps, Seed Rack, White Shelves, and Suitcase. The installation included a root shaped like a dancer, a horse jaw through a tree branch, books weathered into rocks, and a bearded bird. In the brochure for the installation, Purcell explains she is "after...the fact-free, provenance-lacking, bucket-kicking, burnt-out, no-good nameless shard that, in passing, just happens to look like something else." She is expert in classification, and yet she is most interested in objects that avoid characterization.

Purcell has a preference for "objects at the edge of decay," so along one metal wall we find petrified books whose swollen pages are mostly unreadable: they are sculpture now. In another corner of the room entitled "May I Warm You Up: Objects from the Fire," Purcell has placed burned things in neat rows: melted plumbing pipes from a hotel fire, burned scissors, bottles from a bonfire, a burned telephone, and a grave stone that had been recycled into a warming block.

I have been an admirer of Purcell's work for some time, and as the daughter of antique dealers and a collector of natural artifacts, I'm interested in the desire to collect, in the theories surrounding collecting, and in the incarnations of objects. Those who collected in centuries past filled their collections with what they believed was evidence of miracles, yet theories of collecting are both favorable and unfavorable. For example, as Purcell points out, Francis Bacon disapproved of cabinets, calling them sites of "broken knowledge." Freud's theories on collecting have to do with anal retention and childhood toilet training. Then there are the collecting theories of French philosopher Jean Baudrillard: "Surrounded by the objects he possesses, the collector is preeminently the sultan of a secret seraglio." Ralph Waldo Emerson said of cabinets of curiosities, or "arks," (the traditional terms for collections): "causes and spirits are seen through them."

With theories of collecting in mind, I was delighted to encounter Purcell's work in person. I was equally delighted to encounter Susan Howe's new book The Midnight, which also appeals to those of us with a thirst for juxtaposition. It appeals to those who collect because we are always making scientific and/or emotional connections among words and things. Moreover, poets make connections between words because words are mercurial natural artifacts.

Howe and Purcell are artistic contemporaries, and although they may never have met one another or seen one another's work, Susan Howe could caption Purcell's grand project with a single poem from The Midnight:

Counterforce bring me wild hope

non-connection is itself distinct

connection numerous surviving

fair trees wrought with a needle

the merest decorative suggestion

in what appears to be sheer white

muslin a tree fair hunted Daphne

Thinking is willing you are wild

to the weave not to material itself

Howe's line "It's an aesthetic of erasure," from another room of The Midnight, could also describe the sensibility Purcell and Howe share. Erasure is a key concept in contemporary poetry; as scholar/poet Donald Revell has noted: "When history proves useless and consensus chimerical, the poet's necessity is invention, and this does a lot to explain our century's preference for revision over mimesis." With an erasure, the poet does not imitate; the poet revises, crosses out—sometimes leaving in signs of this process, sometimes not. The erasure-ist must consider the following questions: Is what I leave un-crossed out emphasized? Is what I cross out emphasized? Am I working toward narrative or non-narrative writing? What do I want the erasure to say? Is what is crossed out obliterated? Or should readers be able to see what's been erased? What do I say about the erased text in my erasure? Is erasure "correction"? "perfection"? "un-perfection"? Will I do away with the erasures and see what writing is left? A poem? How can an erasure make something "larger" in importance? What words can I add to my erasure to work toward reconstruction?

One thing seems certain: in erasing from a text, the artist inevitably brings a new one into the world. Erasure seems akin to finding work in a cave and bringing it to new light and to new language, and the tears in the original fabric make for other silence that can also be read. In her book Pierce-Arrow (New Directions, 1997), Susan Howe revises, mixes, the manuscripts of Charles Sanders Pierce. She says, "Perhaps the Word, giving rise to all pictures and graphs, is at the center of Pierce's philosophy. There always was and always will be a secret affinity between symbolic logic and poetry." Howe exemplifies her aesthetic of erasure, including allusions to her Pierce project, in her latest work.

The Midnight demonstrates less what poets do with history than what history does to poets, how the residue of history and biology imprints on the poet. The collection is partly an erasure of the works of Robert Louis Stevenson, and partly a autobiographical, non-narrative quest tale whose fabric is woven with photographs of pages from various printed texts.

Howe's quest begins with a series of poems under the heading "Bed Hangings," pieces of history that starched linens hold for the world and for Howe. These are Irish linens some of the time, as Howe's Irish heritage is chronicled in The Midnight. The first sort of "bed hanging" we encounter is a reproduction of a crude Xerox of the tissue paper page between the frontispiece and the title page, taken from Howe's copy of Stevenson's The Master Of Ballantrae. Howe's introduction to The Midnight consists of her brief deliberation on the use for the tissue, which is there to "prevent illustration and text from rubbing together." Merely turn the page after the brief deliberation, and the poetry of The Midnight starts, each poem in the shape of a bed hanging. For example,

A small swatch bluish-green

woolen slight grain in the

weft watered and figured

right fustian should hold

altogether warp and woof

Is the cloven rock misled

Does morning lie what prize

What pine tree wildeyed boy

But why bed hangings? Perhaps the bed and bed linens provide the best image for history and biography, and, at the same time, for the poet's work; the embroidery and care of the linens, the needling of the cloth, the thread, has always been a wonderful metaphor for creation, for writing, Penelope's weaving in Homer's Odyssey leading the way. Howe illuminates some of the mystery of the bed hangings early on in The Midnight. Within the section "Scare Quotes I," which follows "Bed Hangings I," we find a relevant quotation from Ralph Waldo Emerson's essay "Poetry and the Imagination":

Great design belongs to a poem, and is better than any skill of execution,—but how rare!...We want design, and do not forgive the bards if they have only the art of enameling. We want an architect, and they bring us an upholsterer.

We can never accuse Howe of being an upholsterer in The Midnight. The architecture of the work is complex, and we should take a moment to backtrack and acknowledge it here. The book is divided into five sections, alternating what looks like poetry and what looks like prose, or prose poetry: "Bed Hangings I" in poetry, then "Scare Quotes I" in prose, or prose poetry, then "Bed Hangings II" in poetry, and "Scare Quotes II" in prose, and finally, the poetry of "Kidnapped."

Howe relays the Emerson "upholsterer" quotation along with an anecdote about a prolific bed hanging maker, just after the poet defines, in one "Scare Quotes" section, the word "bed":

BED, to lie or rest on. BED of Snakes, a Knot of young

ones. To BED, to pray. Spenc. BED [in Gunnery] is a thick

Plank which lies under a Piece of Ordnance on the Carriage.

To BED with one, is to lie together in the same Bed; most

usually spoken of new married Persons on the first Night.

To BED [Hunting Term] a Roe is said to bed, when she

lodges in a particular Place.

Both the Emerson quotation and the "bed" definition are typical of the kind of entries we find in The Midnight's prose sections. These "Scare Quotes" are especially interesting for the reader who craves arcane knowledge, such as more dictionary definitions, allusion to Edgar Allan Poe's sleep-waker, Orphic plot lines, obsessive compulsive disorders, train whistles, Shakespeare, Greek choruses, and family trees, with most of the images involving sleep and sleeplessness and bedding. The "Scare Quotes" have sub-titles like "cutwork" and "darn" and "traffic control" and "Ovaltine," letting us know that connections between these "Quotes" might only be in the writer's (or her reader's) mind.

The literary in-betweeness of The Midnight recalls for me W. H. Auden's Commonplace Book and contemporary experimental projects that could be called belles lettres, such as Vladimir Nabokov's Pale Fire, Lyn Hejinian's My Life, Franz Kafka's Blue Octavo Notebooks, and Anne Carson's The Beauty Of The Husband, an essay she claims is written in "tangos." But Howe's in-betweeness governs her grammar as well; her lines in The Midnight are not guided by punctuation at all, but by break and by capitalization, everything enjambed. We have to trust in the subjectivity of line breaking. We have to consider that line breaks may not indicate a break in sentence logic. And the poems have no traditional beginnings or endings, like the objects of Purcell's rooms. Note the following "Bed Hanging" poems:

Nor hemp to pleasure pillow

Nor clay scorn to cover as if

sphere of the pent lake hold

Infold me bird and briar you

fathom we cannot to another

declare character in written

summit granite cramp marble

Simple except a blank that it

and later

Glide my shadow through

time curtains will dwindle

Far be it from me whatever

reaction splits into willing

things absolute but absent

are not alone Nominalism

While I lie in you for refuge

it is sanctuary it is refuge

We wait for recognizable phrases like watching a fish come to the water's surface for a bread crumb we've just thrown down ourselves. These two bed hangings may be addressed to a lover. They seem so coded, so secret, so intimate. They might also be addressed to the act of naming, which is the action of poetry itself. Howe's tone seems very like the tone of Emily Dickinson's work here, poems perhaps addressed to the other, or to the creator, or to the act of creation. And like Dickinson, Howe sacrifices sense for sound in her poetry. No surprise, then, that as part of her project in The Midnight, Howe narrates, in her second "Scare Quotes" section, her experience of her library search for Emily Dickinson, or more specifically, Dickinson's original manuscript for "My Life had stood—a Loaded Gun—," which she never gets her hands on, according to her story. Howe pays homage to Dickinson because "She has shown [Howe] that access to the metaphysical is the requirement of a NEED."

We might be tempted to look for the hymn in each "Bed Hanging" because Howe conjures up the "white linen" poet whose work has hymnal structure; after all, Howe provides us a roll call of ministers and sermons in "Scare Quotes I"; and she explains in the definition of "bed" that "to bed" also means "to pray". However, we will not find the hymn meter in Howe's individual poems of the "Bed Hanging" sections (though the poems taken together do sound incantatory). We can look instead to Lewis Carroll's Alice in Wonderland for some clues to Howe's grammatology and her non-applications of grammar in the individual poems.

Standard English grammar can be thanked for the sense that nonsense makes in Alice's adventures underground. Carroll spoofed traditional English education this way. And Carroll's words in the book may have been inventions, but the syntax and parts of speech kept order in the text. The most famous example is from Lewis Carroll's "Jabberwocky," which appears in the "Humpty Dumpty" chapter of Through the Looking-Glass:

Twas brillig and the slithy toves

Did gyre and gimble in the wabe:

All mimsy were the borogoves,

And the mome raths outgrabe.

We comprehend these lines on the level of syntax and can identify the parts of speech. The words "slithy" and "mimsy" are certainly adjectives, while "toves" and "borogoves" and "raths" are certainly nouns. We know that these lines are providing the setting for the nonsense poem.

Howe's syntax, on the other hand, defies diagramming—one is tempted to read the lines backwards as well as forwards, just as in the chess match in Wonderland, to move your man backward was to move your man forward. Yet there is structure to Howe's tropes; for one thing, Howe uses anacoluthon, which causes grammatical inconsistency to be stitched into the same sentence. We might think of anacoluthon as a cousin of portmanteau, a term that Howe uses in its original connotation in the "Bed Hanging" poems. According to Alice In Wonderland, a portmanteau is a "traveling bag which opens, like a book, into two equal compartments." Carroll attached the term to his method of inventing words, words in which "there are two meanings packed up into one word." Howe's title, The Midnight, could even be considered a figurative portmanteau, as midnight is the spliced moment of night and day.

Let us move then from the personalities of double words to the double personalities of phrases. When the line follows the "workings of the mind," starting "according to one pattern and abruptly" changing to another, we have anacoluthon, the way John Frederick Nims defines the term in his book Western Wind. He uses a line from Peter Viereck's "To Helen of Troy (N.Y.)" as an example: "I sit here with the wind is in my hair." We can see an example in the following lines from "Bed Hanging I":

Glide my shadow through

time curtains will dwindle

which might be separated into three different phrases: "Glide my shadow through time" and "through time curtains will dwindle" and "time curtains will dwindle." Meanings are nested in Howe. And we might apply an Alice-esque "Scare Quote" to this nesting of Howe's: "It is fun to be hidden but horrible not be found—the question is how to be isolated without being insulated."

Howe's grammatical play brings to mind the alchemy of the Irish language, Howe's inheritance. When Irish poet Cathal O'Searcaigh talks about poetry, he reminds us of the power of the word, relating that there is no difference between the Irish word for song and the Irish word for poem. The word for "poem" also means "fate," "gift," "offering," and "what is in store for you." The word for a poem's creator actually translates, in O'Searcaigh's mind, to "the one who sees what other have forgotten to see," and when the poet speaks, even the way she speaks the words shifts the meaning. The poet may cure illnesses with poems by saying the poems aloud, but she must have the voice and soul for healing. Likewise, words spoken incorrectly cause harm to the world. Even the clearing of the throat has meaning.

In other examples of the alchemy of Irish, O'Searcaigh is fond of pointing out that the Irish word for "priest" (sagart) might be changed to "little priest" by adding "in" to the word's end (sagartin). However, the word for "little priest" also means "indedible perriwinkle" and "ram with one testicle missing." One must be careful in translating such a word. Along the same lines, the word for "chain," spelled "buarach," might be joined with the word for "die" or "perish," spelled "bais," yet the combination of "buarach" and "bais" or "buarach bais" would not mean "dying chain"; rather, the phrase would translate into "An unbroken hoop of skin cut with incantation for a corpse across the entire body from shoulder to foot sole and wrapped in silk off the colors of the rainbow to produce certain effects by witchcraft." The grammatical constructs of Irish phraseology, we find, make for tricky translation, and Howe's poetry may reflect these underpinnings.

Earlier I chose the term belles lettres for Howe's The Midnight because, like epistolary projects, Howe's book may have a "crisis of destination," a phrase philosopher Jacques Derrida uses for letters that might be lost in the mail, and for when time changes from sender to sendee, and the epistle is no longer immediate. In the case of The Midnight, the project is a difficult one; the poems are syntactically complicated. Yet Howe includes commentary on her process in her finished product. She defines her project throughout her project. At the book's opening, she writes:

For here we are here

B E D H A N G I N G S

daylight does not reach

Vast depth on the wall

Neophyte

and

Revisionist work in

historic interiors spread

from House to MuseumOther documentary evidence

Friends who wish to

remain anonymous

The reader, I assume, is the "Neophyte," who must learn that the Bed Hangings prevent illumination. They prevent the reader from looking out into the day. We must read them and not the world beyond. The Bed Hanging is all the world one needs. It is the personal history and biology; it is the inheritance.

But what happens when the people in the house create something that must move outside the house, or from "House to Museum"? This is the ancient quandary of audience. Alice Walker has said that she thinks it's important for people, writers in particular, to be bilingual, but she doesn't mean that people need to be able to use two entirely different languages from two different cultures. What she is referring to is her ability to remember the simple English that her mother and father spoke when she lived at home, which is an entirely different language (though still English) from the one she writes in. Both are extremely important, and sometimes they overlap, but they are never the same language. I think Howe is addressing a similar issue. What happens when the embroidery, the craft of linen, goes out on display? What happens when craft becomes art? Or is taken as seriously as art, when it's normally been taken seriously as inheritance? A poet must consider these questions as part of her process. How does one reconcile the Bed Hanging of one's childhood and the Bed Hanging of one's adulthood? Perhaps this is a good time to bring in Howe's definition of poetry: "the impossibility of plainness rendered in plainest form." And here is another example of "the impossibility of plainness," an excerpt from the very last poem of the book:

Style in one stray sitting I

approach sometime in plain

handmade rag wove costume

awry what I long for array

Howe comes before her style wearing simple clothes made by hand. She perhaps is humbled by her own approach. And she is even more specific about her process in "Scare Quotes I," where she again sounds so like Rosamond Purcell:

I am assembling materials for a recurrent return somewhere. Familiar sound textures, deliverances, vagabond quotations, preservations, wilderness shrubs, little resuscitated patterns. Historical or miraculous. Thousands of correlations have to be sliced and spliced. In the analytic hour that is night in which Olmsted, not being able to see what has happened in his mind with regard to his mother, sleeplessly exists, perhaps there is the surety that after a silence she will contact him again in bits. Escape may be through that dawning light just filtering through the blinds. After all he is forty-five, and certainly not a child.

Olmsted is one of the many members of the cast of characters that appear in The Midnight, most of them actual historical figures. He was the first-born son of Charlotte Hull Olmsted and superintendent of the construction of Central Park in New York City. When Olmsted appears in The Midnight, the text focuses on two of the most important themes that run through the book: sleep and sleeplessness and the mother, the motifs of midnight. Howe says in one "Scare Quote," "Furthermore I am now writing from a dreamer's point of view." She follows the statement with an anecdote that could apply to the speaker of The Midnight as well as to Alice in Wonderland:

In the dream we heard from high above the sound of splintering glass. A birdwoman had flown in by accident, and got trapped. She could have been a dancer, or an actor using any number of prosthetic devices. We are all outfitted with prejudices over a long period of years. Wired and hardwired. Cut one tree down for fuel, another for rural philanthropy. Bits of wall and broken window frames get tangled in times of crises, even the cleanup of large oil spills. It's the split between our need to communicate and our need to understand when the other one signals. This is why some people fly in their sleep over urban escarpments. Anxious about communicating in a foreign language, she offered a different route to salvation. I aligned myself with half of her history as if it were a lifebelt.

Howe continues the anecdote in the next paragraph of the "Scare Quote": "She trusted no one. She kept signaling us to come up and free her. We couldn't. I have an uneasy feeling she is still in the building and we will have to work quickly if"

A bird in the house, according to the superstitious, is a bad omen. What about a birdwoman trapped inside one? She is like Alice, who grows large once she has already stepped inside a house in Wonderland. One of her large arms reaches out of a window, and she becomes a monster who frightens the residents of Wonderland as much as they frighten her. Alice has already unnerved the locals because she has never been able to speak their language. Her gigantism adds insult to injury. She becomes a metaphor for a crisis in communication, like the birdwoman of The Midnight, only the birdwoman is somehow a salvation for the speaker of the "Scare Quote," maybe because she provides an image for the speaker's literary crisis of destination.

Howe follows the dream of the birdwoman with an anecdote about her own mother, and a comment about how perhaps a child may be able to perceive a deeper reality in terms of a parent, even while the child might never be able to see the parent as she truly is.

We have finally come to the muse of Howe's collection. Howe punctuates The Midnight with pictures and stories of her mother, "Dublin girl" Mary Manning, who was an author herself, an actress, and a lover of Yeats poetry. Howe walks in her footsteps. At the beginning of this essay, I said that The Midnight was a quest tale, but a quest for what? In the old Arthurian tales, alluded to in The Midnight, the hero has a number of tasks. He walks around a tower and a fountain. He saves someone. The hero learns he has committed the sin of pride. Perhaps the hero sees god at the end and disappears because no one survives a deity's gaze. What is our speaker questing for? At the end of the second "Scare Quote," Howe writes:

Envoy

Midnight is here. The brig Covenant. I go in quest of my inheritance. Portmanteau for a voyage—hazel wand—firings—tattered military coat and so on. Are the children asleep? All who read must cross the divide—one from the other. Towards whom am I floating? I'll tie a rope round your waist if you say who you are. Remember we are traveling as relations.

Well it's the way of the world

Howe expresses here the necessary symbiosis between writer and reader. Howe finds the relationship adventurous, not the wound that Franz Kafka always thought it was. Her inheritance is the word that Mary Manning has brought her. The Midnight is Howe's work at reconciling the issues of her inheritance. Most little girls of her generation were handed the starched linens and aphorisms of their mothers, the literal Bed Hangings and Scare Quotes. Howe was handed a loaded language. She wills that language to us.

I would like to end with another look at Rosamond Purcell's aesthetic here, and describe a final bed hanging, the oddest example of sewing I've ever seen. Purcell's photograph of a Harvard University Museum artifact shows a detail of a square of shiny yellow fabric. Three rows of long needles, about three hundred in all, are threaded with the eyes upward through the cloth. The cloth looks golden around the needles and their impressions, dark and light gold, like a wheat field under cloud shadows. Her caption reads:

These needles taken from the body of an insane woman after her death reflect not only the extraordinary mental anguish of a morphine addict but also the peculiar sensibility of whoever arranged the morbid collection with such care; it is as though the needles, once a source of frantic and fruitless anticipation, might now be used methodically by a person mending clothes.

Apparently the morphine addict who used these needles in the mid-19th century believed that the drug came inside every needle. Now they are "mounted tidily" as if by a seamstress, a most frightening inheritance. A witchy presentation.

We might be reminded that when Howe says, "It's an aesthetic of erasure" in The Midnight, she's actually referring to the very first seamstress of bed hangings, Thorgunna of the 11th century, who embroidered so fantastically that she was accused of practicing witchcraft. Gossip deepened, darkened, until she declared that "ownership of her hangings could mean curtains" for the owner. She tossed or burned her existing tapestries in "an aesthetic of erasure." What lasts are the corroded needles that can injure cloth in something sublime, that can injure cloth into poems. What lasts is language.

Click here to purchase this book at your local independent bookstore

Rain Taxi Online Edition, Winter 2003/2004 | © Rain Taxi, Inc. 2003/2004

Barbara Guest

Barbara Guest