photo by Ebru Yildiz

by Benjamin P. Davis

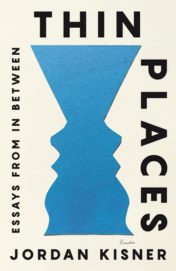

I first encountered the work of Jordan Kisner via her essay about the scholar and activist Silvia Federici entitled “The Lockdown Shows How the Economy Exploits Women. She Already Knew,” a piece that teems with the transformative possibilities of social action. In the context of pandemic-related pessimism, I felt energized by Kisner and Federici’s conversations. While they took place on simple walks through a park, these conversations were also global, looking to Indigenous politics across the Americas in order to consider ways of living in human community that offer alternatives to the exploitation of capitalism. This led me to seek out Kisner’s essay collection, Thin Places: Essays from In Between (Picador, $18), where I found that her analysis of big issues was set alongside generous personal reflection and insightful commentary on the symbols, habits, and gestures that make everyday life meaningful. To talk more about these connections between the structural and the personal, I reached out to Kisner in early 2021. What follows is the result of our slowly thinking together over the course of the year.

I first encountered the work of Jordan Kisner via her essay about the scholar and activist Silvia Federici entitled “The Lockdown Shows How the Economy Exploits Women. She Already Knew,” a piece that teems with the transformative possibilities of social action. In the context of pandemic-related pessimism, I felt energized by Kisner and Federici’s conversations. While they took place on simple walks through a park, these conversations were also global, looking to Indigenous politics across the Americas in order to consider ways of living in human community that offer alternatives to the exploitation of capitalism. This led me to seek out Kisner’s essay collection, Thin Places: Essays from In Between (Picador, $18), where I found that her analysis of big issues was set alongside generous personal reflection and insightful commentary on the symbols, habits, and gestures that make everyday life meaningful. To talk more about these connections between the structural and the personal, I reached out to Kisner in early 2021. What follows is the result of our slowly thinking together over the course of the year.

Benjamin P. Davis: In your essays you take the tone of a fellow traveler, as opposed to an omniscient commentator. For example, there’s a moment in Thin Places, in the piece “Habitus,” where you pause to tell your reader about what had been preventing you from writing that essay: “I had it all in mind, and still I experienced that feeling of inability every time I sat down to write, a panic more precise than writer’s block, more a failure of ethics than of imagination or creativity.” Speaking about what prevents her from writing is something Gloria Anzaldúa, a key figure in “Habitus,” does as well. Can you say more about that decision—to tell your reader about your difficulty in finishing the essay?

Jordan Kisner: I love the phrase you use, “fellow traveler,” because that describes the way I want a relationship between a writer and a reader to feel—companionable and bonded by shared curiosity. I find myself attracted to that feeling as a reader, and I want to cultivate it when I write. Still, the moment you point to in “Habitus,” where I hit a wall in the process and confess that directly to the reader, felt like a risk. Writers struggle often with the writing process, and that is rarely as interesting as the subject they’re struggling with. In this case, I decided to include it because the reason I was having a hard time writing turned out to be an example of the phenomenon the essay was trying to describe: In many places in this country, your goodness, your respectability, even your safety are contingent on your compliance with a version of “American-ness” that champions nationalism, whiteness, affluence, and conformity—and living in that kind of cultural atmosphere leads some people who don’t fit those descriptors to feel obliged to contort or hide parts of themselves and their histories to fit the script, so to speak.

I was struggling to say what I wanted to say about these dynamics because the only way I could do so with any reasonable authority was to relay my own experience as a daughter and granddaughter of a Mexican-American family from South Texas with a complicated relationship to American identity, whiteness, passing, and shame—and I had the sense that to write about that in public would cause conflict with and embarrassment for my family. (I also look more like my father’s side of the family, which adds a layer of anxiety and impostor syndrome to the prospect of writing about these subjects.)

When I had gotten my mother’s blessing to write about some of her experiences growing up, I knew that I wanted to include a mention of my block and anxiety to emphasize how intense and intergenerational the pressure not to talk about these subjects can be. It also simply felt like the most honest thing I could do at that point in the essay—to admit failure and proceed from there.

BPD: In the line I quoted above, you wrote of a “failure of ethics” in drafting the piece. When I write more personal essays, I always run into the fact that life as it is lived is so much more complicated than life as it is told—I find myself choosing between portraying the experience as I recall it, with all the missteps and complications, or making it more palatable. In Thin Places, you consistently portray experience through all of its imperfect recollection, showing us ethical complications of life as it is lived while acknowledging that most of us consider “the fantasy of escaping into some system of blinding simplicity and idealism.” Why is it important to stay close to reality in essays, even and especially as that involves sharing moments of ethical failure?

JK: I think there’s a strong ethical argument for choosing to retain nuance and complication in an essay, but honestly, I make that choice—when I do, which I hope is more often than not—for reasons of practicality and aesthetics. Complication, messiness, hesitation, and fallibility are interesting! An untidy narrative is more engaging than a tidy one, and a writer wrestling with her own fallibility is more exciting to me than one who elides it. The impulse to present a seamless, unimpeachable story or argument is so strong, but it’s worth asking: who and what purpose does that serve? If you are trying to write what is true, useful, and compelling, the reality of the situation is typically better than what you might invent to smooth the rough edges.

BPD: “Habitus” is not only the title of the aforementioned essay, but it is also a key word running through Thin Places, one that reverberates across other essays. In “The Big Empty,” for instance, you define it as “a sociological term for the ways habits of body and mind are created by imitating those around you, and the way groups of people form coherent social practices.” What about this concept holds so much significance for you?

JK: I find myself susceptible to this phenomenon, and so it intrigues and vexes me. I have a strong mimicking impulse, whether it’s accidentally picking up other people’s gestures, accents, or turns of phrase. I’ve always chalked this up to curiosity and delight—I like people, and I like discovering all the various ways of being one can manifest. I’ve also always suspected that this trait makes me more susceptible to having a worldview, or a habitus, that is heavily influenced by my surroundings. This seems both like a beautiful thing (communities form coherent identities because we need and care for each other; I love that I carry the mannerisms of people I have loved) and a fraught one: how much do I determine my own worldview? Is such a thing even possible? Desirable? What are the habits of mind and body I am absorbing from the culture(s) in which I live—can I even see them clearly?

BPD: On the point of soaking up our surroundings, your essays suggest that how we see and occupy space is not only a political question, but also, fascinatingly, a theological question. You argue that it matters if, with the twentieth-century mystic Simone Weil, we learn to cultivate a prayerful habit of attention; it matters if, with the contemporary poet and superb reader of Weil Christian Wiman, we feel a “universally animate energy.” What is it about attention that can lead to what you call “praying by looking”?

JK: I’m compelled by Weil’s idea that attention is prayer. It seems true to me that paying attention to something is a form of devotion, and that offering your absolute attention brings you closer to an experience of the absolute. I don’t pray in any religious sense, but I think the habit of paying true attention—to each other, to our environment, to the space we occupy together—makes us better, though it can also be uncomfortable. Cultivating that habit of attention makes me a better writer when I can manage it.

BPD: Can you say more about how attention can be uncomfortable?

JK: There’s a conference of mourning doves outside my window right now, which has been going on for probably a half an hour, though I only just noticed it. They’re having their breakfast, eating seeds off the ground. I’m happy to see them, my bird neighbors, though now that I’m looking at them I’m also thinking about the fact that the particular soil they’re eating their seeds off of isn’t safe for humans to grow our own food in due to decades of contamination and poor care. Is there anything I can do about this little patch of dirt to rehabilitate it? When would I have time for that? But what am I busy with, and is it really more important than that? Paying attention is always like that: delight and sorrow and self-implication.

BPD: Two other themes of your essays are waiting and listening. “I waited for the real moment when I’d know what to build a life on and how to be,” you write in “Attunement”; “It didn’t come.” And your epigraph cites Mary Ruefle’s line “I continue to write because I have not yet heard what I have been listening to.” What is the potential, perhaps even the ethical potential, you find in waiting and listening?

JK: Back when I was starting Thin Places, I said to a friend that I wanted to write a book full of people waiting for things. The emotional and spiritual tension of waiting for something as yet withheld is fascinating—for one thing, it mirrors the experience of reading a good story or essay, in which the reader is held artfully in suspense until the ending, with its answers or resolutions, arrives. To feel that feeling in real time—“Where does my own plot go next? What is its meaning?”—is an exciting, terrifying experience, and probably a universal one. It can be tempting (for me, at least) to want to force myself past the waiting and into some kind of action or determinative feeling or thought, but I started to realize that that’s often driven by impatience and anxiety—and that there’s a lot you’ll miss in the way of observations, opportunities, self-knowledge, creative potential, even relationships, if you’re unwilling to be held in suspense.

BPD: In what I take to be poking fun, in “Attunement” you describe your M.F.A. program as “going to classes with people who worked for hours on a single sentence and talk[ing] about devoting themselves to catching inspiration and channeling it into book form.” How does this dual sense of work and devotion play out in composing essays for you?

JK: I was poking fun, I suppose, but also I found it moving to be surrounded by people who treated as sacred something I feel to be sacred, especially after having worked in a corner of corporate publishing that was pretty mercenary and jaded. I find it’s important to be earnest about things—to really care about what you care about, without reservation or disguise—while trying to correct for an attitude of preciousness that can creep in when you’re doing creative work. Light self-mockery is a good way to bring myself back in line.

Early on, writing felt more to me like devotion than like work. I only knew how to write when “inspired,” which meant that I often didn’t write. Learning to treat it like work, like a practice that I sit down to do whether or not I’m feeling inspired, felt key to making a sustainable life and to making the amount and quality of work I wanted to. (Inasmuch as I have—this remains a work in progress.) I find it easier to think of writing as a practice than as a job. Maybe that’s because practices can retain a devotional quality. You engage an ongoing practice (like writing, painting, meditation, whatever) out of desire and curiosity rather than as a means to a 401k.

BPD: Writing in The New York Times Book Review, Lauren Christensen called your writing “ethnography.” Would you agree? How do you think about your method?

JK: I’ve never thought of my work as ethnography, but I understand why someone might suggest that. I do often find myself in the position of trying to decipher the ideologies or customs of some group of people. But I think where my work fails to be ethnography is that I’m always implicated in the group being observed. Because all these essays take place in America, I’m part of the culture that’s under inspection, and usually there’s some personal curiosity that has drawn me to the scene. The implied distance of the ethnographer can’t really exist in that case.

I don’t have a notion of my method, per se. When reporting or interviewing, I tend to think of myself as simply asking people to tell me what they care about, and working hard to be a critical, kind, worthy recipient of the confidence they’re placing in me by answering. When making essays I usually have two gestures in mind, one structural/intellectual and one relational: writing toward what I don’t yet understand and writing as though I’m speaking directly to someone I care about.

BPD: Also on the point of working very hard, in April of 2021, you spoke with the Marxist feminist Silvia Federici about how U.S. society undervalues domestic labor. In that article, you observe that the 2016 prayer camps at Standing Rock, and in particular the practice of “commoning” that occurred there, provide a corrective to unwaged domestic labor. “Everyday life is the primary terrain of social change,” you quote from Federici. Thin Places portrays everyday life across the country as well as across class and identities. What’s at stake for you in writing about this terrain?

JK: If you believe Federici that major social change happens at the level of the mundane or daily (which I do), then writing about “everyday life” could be part of producing the social change you wish to see. I’m not necessarily that kind of writer—if there’s any social change I hope to bring about with my writing then it will be pretty obliquely accomplished.

Everyday life is also all of life, practically speaking. We only get life in days, and all days combine something of the mundane and the marvelous, no matter whose day you’re considering. I enjoy writing with the daily in mind because I find it beautiful and strange and sometimes terrible. It’s what I want to spend my time thinking about.

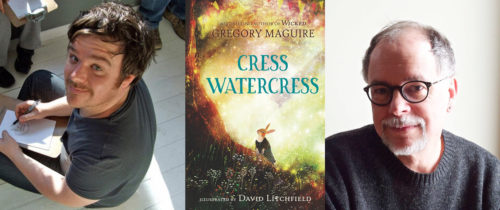

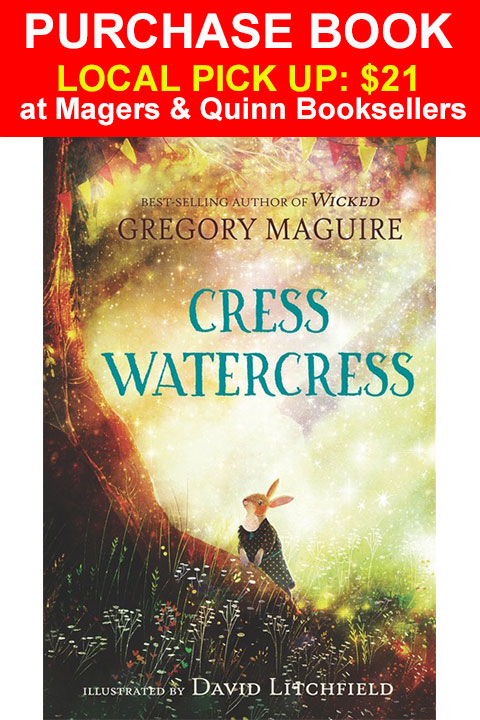

Gregory Maguire is the author of the incredibly popular books in the Wicked Years series, including Wicked: The Life and Times of the Wicked Witch of the West, which inspired the musical. He is also the author of several books for children, including What-the-Dickens, a New York Times bestseller, and Egg & Spoon, a New York Times Book Review Notable Children’s Book of the Year. Gregory Maguire lives outside Boston.

Gregory Maguire is the author of the incredibly popular books in the Wicked Years series, including Wicked: The Life and Times of the Wicked Witch of the West, which inspired the musical. He is also the author of several books for children, including What-the-Dickens, a New York Times bestseller, and Egg & Spoon, a New York Times Book Review Notable Children’s Book of the Year. Gregory Maguire lives outside Boston. David Litchfield started to draw when he was very young, creating comics for his older brother and sister. Since then his work has appeared in magazines, newspapers, and books and on T-shirts. His first picture book, The Bear and the Piano, won the Waterstones Children's Book Prize. He is also the illustrator of Rain Before Rainbows by Smriti Prasadam-Halls and War Is Over by David Almond. David Litchfield lives in England.

David Litchfield started to draw when he was very young, creating comics for his older brother and sister. Since then his work has appeared in magazines, newspapers, and books and on T-shirts. His first picture book, The Bear and the Piano, won the Waterstones Children's Book Prize. He is also the illustrator of Rain Before Rainbows by Smriti Prasadam-Halls and War Is Over by David Almond. David Litchfield lives in England. Ann Patchett is the author of eight novels, four works of nonfiction, and two children's books. She has been the recipient of numerous awards, including the PEN/Faulkner, the Women's Prize in the U.K., and the Book Sense Book of the Year. Her work has been translated into more than thirty languages. She lives in Nashville, Tennessee, where she is the co-owner of Parnassus Books.

Ann Patchett is the author of eight novels, four works of nonfiction, and two children's books. She has been the recipient of numerous awards, including the PEN/Faulkner, the Women's Prize in the U.K., and the Book Sense Book of the Year. Her work has been translated into more than thirty languages. She lives in Nashville, Tennessee, where she is the co-owner of Parnassus Books.

by Marina Chen

by Marina Chen